This report was translated into Korean with thanks to the Korea Press Foundation. It is available to download here.

Executive Summary

The last few years have seen an explosion of online video, driven by technical improvements, initiatives from platforms like Facebook, and investment by media companies in new visual storytelling formats. But to what extent are consumers embracing news video? Is this an incremental addition to the digital landscape or another fundamental disruption requiring urgent and immediate action?

In this Reuters Institute report, we combine data on video consumption and production from a number of key sources with more than 30 interviews from news organisations across Europe and North America. On the basis of this evidence, we find the following:

- So far, the growth around online video news seems to be largely driven by technology, platforms, and publishers rather than by strong consumer demand. Website users in particular remain resistant to online video news with only around 2.5% of average visit time spent on video pages in a range of 30 online news sites; 97.5% of time is still spent with text. Around 75% of respondents to a Reuters Institute survey of 26 countries said they only occasionally (or never) use video news online.

- Having said that, interest in video news does increase significantly when there is a big breaking news based on log file evidence provided to us by the BBC around the Paris attacks, the percentage of users accessing video per visit doubled from around 10% on a normal day to 22% immediately after the attack. Online video news provides a powerful and popular way of covering compelling stories, but not all everyday news coverage is equally compelling.

- Meanwhile, off-site news video consumption is growing fast. Many publishers we interviewed said that the majority of their video is now consumed through Facebook and other platforms. Some individual viral videos we studied for this report have had 75–100 million views, far more than they could ever have expected using their own websites; however, many other videos sink without trace.

- We find that the most successful off-site and social videos tend to be short (under one minute), are designed to work with no sound (with subtitles), focus on soft news, and have a strong emotional element. Given the growing importance of social media as a source of news, this very different format is arguably already affecting the content and tone of news coverage in general.

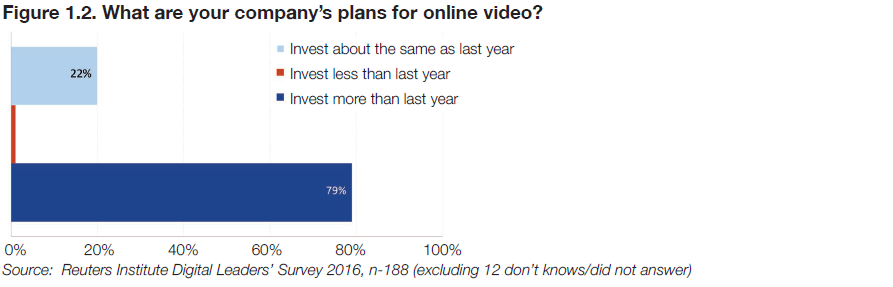

- Publishers are beginning to embrace online news video, with 79% of senior digital news leaders surveyed by the Reuters Institute at the start of 2016 saying they would be investing more during the year. We find a number of traditional publishers planning major initiatives (e.g. BBC’s Ten to Watch) but others are just dipping their toes in the water. Most news organisations are in an experimental phase; they are nervous about the significant investment required, the difficulty of scaling video, and the uncertain path to commercial return.

- Broadcasters should be in the best position to take advantage of the move to video with a wealth of relevant skills, but in many cases we find them struggling to adapt to the new grammar of digital online video. By contrast, both newspapers and digital-born companies have had to build capacity and skills from scratch. Newspapers, in a period of retrenchment, have found it challenging to fund new investment and retrain a predominantly text-based workforce. Digital-born companies have been better equipped to take risks in new formats and distribution but many have become dependent on powerful platforms over which they have little control.

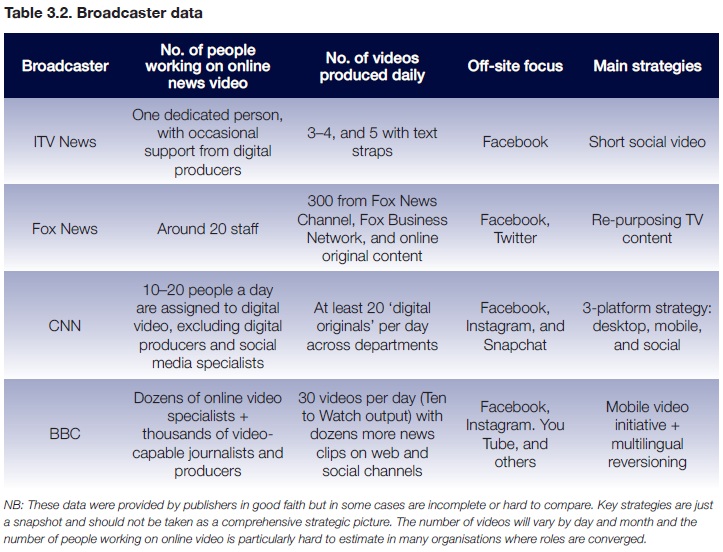

- We find varying approaches to resourcing and organising online video news production. We interviewed the following: news organisations that have only one or two people working on online news video; news organisations with large and well-established teams that operate largely independently from the main newsroom; and, finally, publishers that have tried to fully integrate online video into the commissioning and the production of their journalism.

- Issues of scale and technology are particularly pressing. Producing videos can be a time-consuming process using legacy systems, while digital-born competitors have better technology but are under pressure to create more and more content with the same number of staff. Automated or semi- automated software is emerging to help solve these issues.

- The monetisation of online news video remains the biggest challenge for publishers. On-site monetisation continues to focus on pre-roll ads, despite widespread acknowledgement that this is a poor user experience that is affecting growth. Off-site monetisation is also problematic with much depending on the outcome of various Facebook product initiatives. To overcome these challenges, publishers are creating sponsored or branded content but many are struggling to scale this approach given the often bespoke nature of video production.

Overall, we are cautious about the long-term dynamics for video news in particular. Although there has been a significant growth in online video, much of this has been in social networks and around softer news and lifestyle content (or premium drama and sports on demand), not news. Video that adds drama and immediacy is now valued and expected by consumers on news websites, but only up to a point and in certain circumstances, with both young and old still valuing the control and flexibility of text. Although we are likely to see considerable innovation in both formats and production over the next few years, it is hard to see video replacing text in terms of the range of stories and the depth of comment and analysis traditionally generated by publishers. The high commercial returns currently available around video are unlikely to last if, as expected, more investment and more automated systems lead to a substantial increase in the supply of content, thus driving down advertising rates.

Introduction

Every year we see new evidence of the exponential growth of video distributed over the internet and projections of further increases to come (Ericsson, 2015). Much of this relates to the rise of the ‘over-the-top’ entertainment content from the likes of Netflix and Amazon, which is essentially a new way of delivering television on demand. But we are also seeing the emergence of a new kind of ‘native’ video that is made for the web itself. This content tends to be short form and is created by traditional publishers, specialist digital-born brands, agencies, and companies, or indeed any individual with the desire to do so.

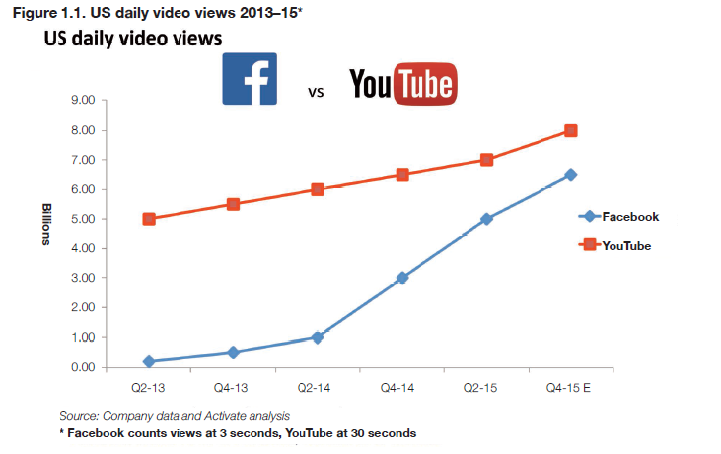

Smartphones and tablets with high-definition screens have enabled consumers to watch videos anywhere, while on-board cameras, apps, and simple editing software have lowered barriers to entry for content creation. At the same time, bandwidth has become cheaper and more plentiful with the cost of mobile data plans falling in many countries. Over the last year in particular, social networks like Twitter and Facebook have embraced these trends with news feeds filling up with videos, enabling extraordinary levels of intentional and accidental exposure to these new native formats. Facebook’s video consumption has increased by 75% in the past year, reaching 8 billion daily video views; over 1.5 million small businesses posted a video (or a video ad) on Facebook in September 2015. 1

These developments coincide with the first fall in TV news viewership after decades of continuous growth (Newman et al. 2016). in countries such as the UK, the USA, and France, a fall in viewership of television news bulletins has been documented, especially among the young but also in the population as a whole (Nielsen and Sambrook, 2016). The advent of new services like Periscope and Facebook live means that the video-enabled internet is now often the first port of call for big breaking news events like the Paris and Brussels attacks. Furthermore, Facebook’s native player with autoplay functionality has helped it catch up with Youtube as the premier destination for online video in general, of which news is a significant part.

The foremost motive for investing in online news video is that, in this day and age, consumers expect to see video content in their news feed. 2

Edward Adams, Video News Editor, Telegraph Media Group

With Facebook and Youtube offering powerful new distribution platforms, publishers have felt compelled to experiment with new formats and new ways of reaching audiences.

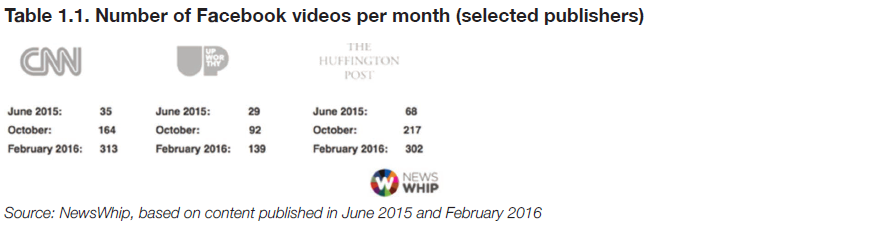

Responding to these new opportunities, publishers like CNN and the Huffington Post have increased the amount of short-form video posted to Facebook by between five and tenfold in less than a year.

Broadcast and print organisations are forced to adapt to rapid changes in consumer behaviour including a greater reliance on mobile and social media as a source of news. This is making it harder and harder for publishers to capture the attention of viewers for more than a few minutes and to maintain a direct relationship with audiences; these trends are making it more difficult to monetise content. With other revenue streams faltering, the hope is that online video can re-energise the digital advertising market at the same time as providing better ways of engaging audiences. Against this background, it is not surprising that in a recent survey for the Reuters Institute, 79% of CEOs, editors, and digital leaders said they planned to invest more in online video this year.

But in this rush to video, some industry veterans remain cautious: ‘I don’t think video is going to be the saviour,’ says Jason Mills, Head of Digital at ITV News. ‘There will be masses and masses of video out there.’ 3

Acknowledging the widespread discussion about the future of video, this report sets out to explore emerging consumption patterns as well as the online video strategies of leading publishers. More particularly, we are interested in identifying the opportunities and challenges publishers face in the production and monetisation of online news videos. To understand the online news video strategies, we interviewed 30 heads of video, heads of digital, or editors-in-chief working in publishers in the UK, the USA, Germany, and Italy. The choice of these countries allowed us to capture the trends in markets with different dynamics and different levels of digital news consumption. The interviews were conducted between december 2015 and February 2016.

The online video consumption section of the report is based on a range of web analytics sources that measure actual usage as well as our own survey data.

- Survey data was taken from the Reuters Institute’s Digital News Reports from 2014 until 2016. These surveys employ representative samples of the online population of up to 26 countries.

- To measure on-site web traffic data, we used data from Chartbeat, a web analytics company that measures both the text and video performance of publisher websites using a tagging methodology. We have data from ten outlets (four broadcasters, four print outlets, and two digital-born outlets), half of which are based in the USA.

- To identify which outlets and which news videos are successful off-site, we employed data from Newswhip, a company which tracks the distribution of news stories in social media along with levels of engagement.

- We also take a deep dive into one of the most important stories of 2015 (the attacks in Paris) using data provided by the BBC. We explore how this traditional news organisation used online news video on the day of the attacks as well as in the week following the events.

In chapter 3, we map the digital video production strategies of news outlets in four different countries (UK, USA, Germany, and Italy). In chapter 4, we identify opportunities and challenges for the investment and monetisation of online news video. In the final chapter (chapter 5), we go through the main findings and outline our thoughts about the future of online news video.

Online video consumption

In this chapter, we look at how frequently and where online news video is consumed on and off-site. More specifically, we use data from different sources to understand how prominent online news video is, what kind of video is more successful, and on which platforms and devices people watch online news video. Finally, we examine how one publisher (the BBC) uses online news video in a breaking news situation.

Use of Online News Video: A Sluggish Growth

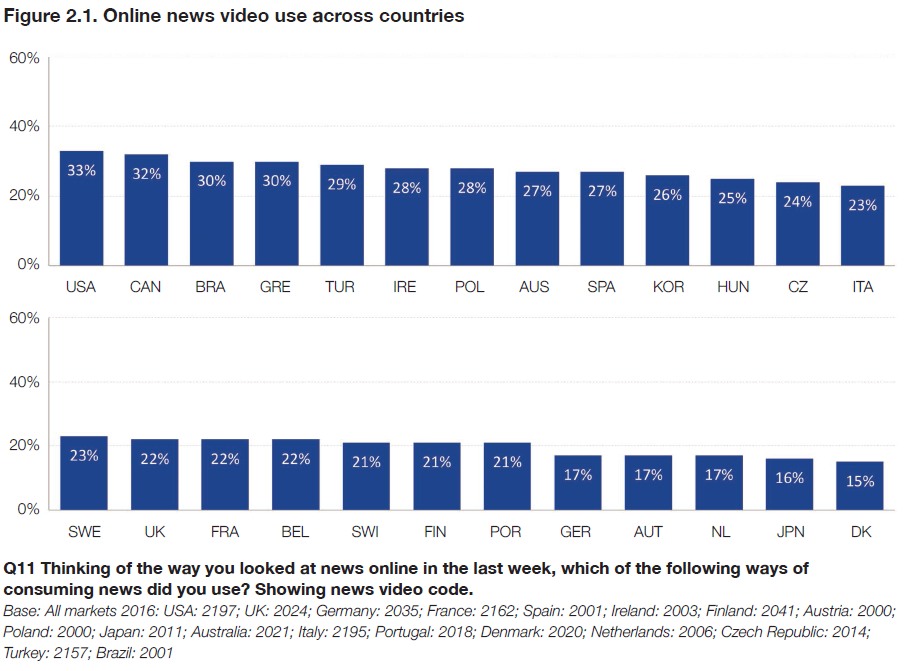

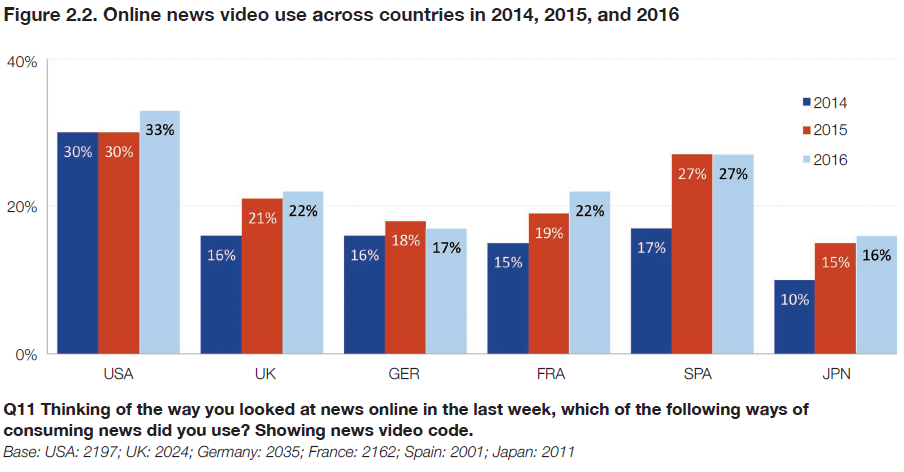

To measure the prominence of online news video in 26 countries historically, we look at survey data gathered for the Digital News Report 2016 (Newman et al., 2016). First we examine how many people consume news via online news video in 26 countries in 2016. Across all countries, around a quarter (24%) of our sample claimed to view online news video in a given week. If we look at the numbers by country (Figure 2.1), we find that the results vary from 33% in the USA and 32% in Canada to 15% in Denmark and 16% in Japan.

For some countries, we have historic data on the use of video in 2014 and 2015. The comparison of these data with 2016 is presented in the graphs below. While in some countries like the UK or Spain we saw a substantial rise in online news video use from 2014 to 2015, the numbers from 2015 to 2016 were either stable or only growing slowly.

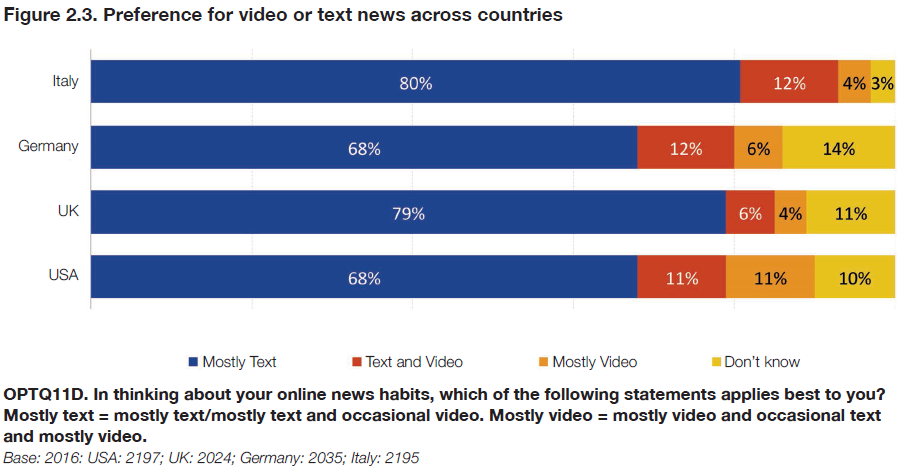

We also found that text is largely preferred over video for each of the 26 countries in this report, with the share of respondents that prefer text ranging from 68% in the USA and Germany to 80% in Italy. Preference of video over text was higher in the USA (11%), while it was lower (4%–6%) in the other three countries.

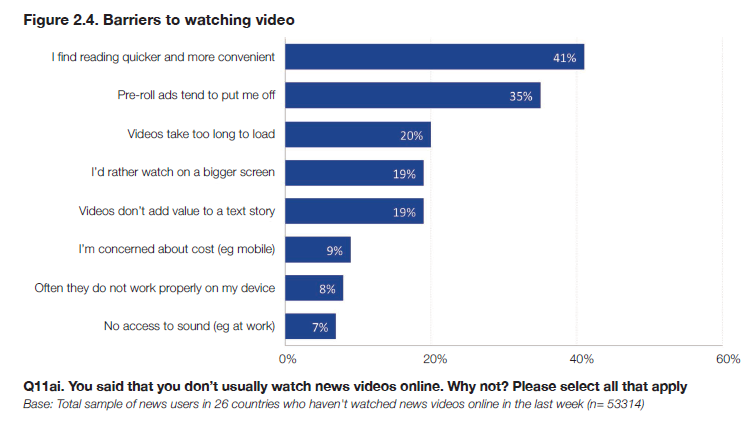

We also asked those who say that they do not use online video news about some of the main reasons for their lack of interest in the format. We should note here that the video-avoidant users were the large majority of the Digital News Report survey respondents (76% across all 26 countries).

These data show that while technological barriers (speed, screen size, dataset cost) are not the primary reasons why people do not watch video, they put off a significant share of people from watching it. However, two other barriers should be more worrying to publishers and advertisers: a significant proportion of respondents (41%) think that reading articles is quicker and more convenient than watching video news, and 19% feel that videos don’t add value to a text story. It is noteworthy that pre-roll ads put off a third of non-users from watching news video.

Surprisingly, across our entire panel, most online news video is consumed on a laptop or desktop computer (46%), followed by smartphone (18%), and tablet (9%). Under-35s are more likely to use a smartphone, but only to the extent that they use these devices more anyway.

On-site and distributed video

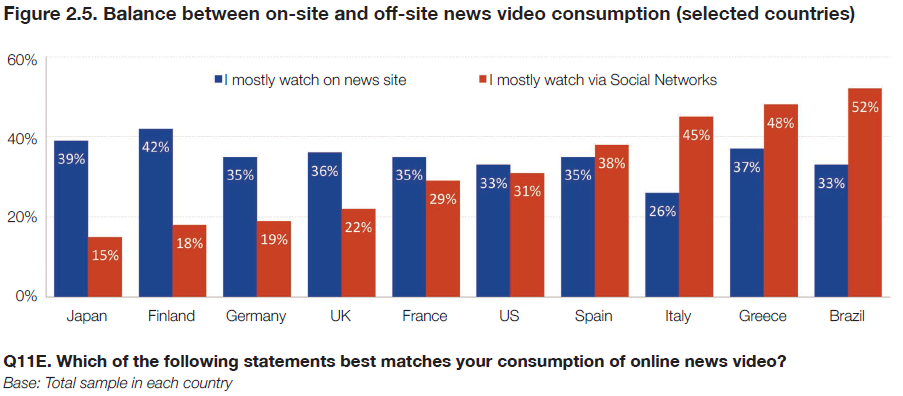

The numbers on Facebook consumption presented in the introduction show the growth of off-site consumption in the past few years. this is backed up by our survey findings (see Figure 2.5) that show that off-site news video consumption is now higher than on-site consumption in countries with high social media news reading (Spain, Greece, Brazil). In countries that use social media less for news, such as Japan and Germany, the share of off-site video consumption is smaller but still noteworthy.

It is also worth highlighting that in each of the 26 countries, the share of young respondents (<35) watching videos via social networks was higher than the general population, something that indicates that the future of online news consumption might be geared towards off-site consumption.

On-site analytics

To understand online news consumption patterns on-site, we analysed data provided by Chartbeat, a web analytics company commonly used by news publishers that has also started to work with video. We analysed a dataset that consisted of 30 outlets, nine broadcasters, six digital- born and 15 print outlets (the outlets are anonymous). Fifteen outlets are hard news outlets, while the other 15 outlets had a mixture of news and soft news content. in addition, 17 outlets were American and 13 from other countries. The data for all these websites are from 1 December 2015 to 29 February 2016.

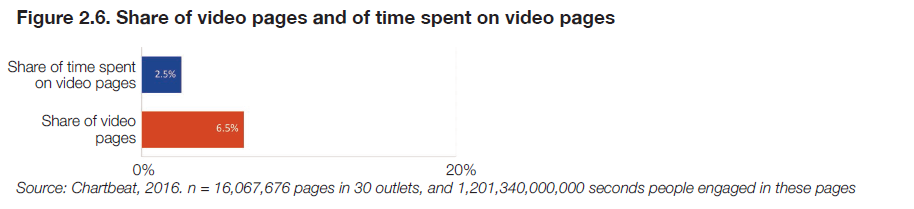

To examine how prominent the pages with videos are in these websites, we measured how many pages in the domains of these outlets contained video and how much time unique visitors spent on these pages as a share of the total time spent in the domains. On average, video was present in 6.5% of the pages of the domains of these news publishers, though we also found considerable variation in these numbers reflecting different levels of investment. Video pages in outlets varied from 0.25% in a digital-born outlet to 34% in the website of a broadcaster.

Then we looked at how much time was spent on these video pages as a share of the total time spent in these domains per unique visit. although there was considerable variation between websites, 4 We found that on average, video accounted for 2.5% of total time spent on these websites, a result that indicates a lack of audience attention on pages that contain video, given that 6.5% of pages contained video. The vast majority of time spent (97.5%) on these outlets was engaging with text, something that connects to our earlier survey finding showing a very strong preference of text over video news in all 26 countries in the panel.

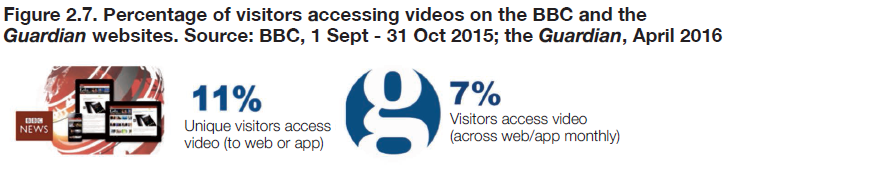

We checked these findings directly with a number of publishers who confirmed that both the proportion of visitors and the share of time spent on video were generally around 10%, though it was often much below that. Corroboration comes from data provided by the BBC, a broadcaster that makes a considerable amount of video available on its news website. Looking at a two-month period (September–October 2015), 11% of visitors to the BBC News website and BBC News app used video. we found no substantial difference between the share of unique browsers watching video on weekdays or at the weekend. data provided by the Guardian for April 2016 show 6.8% (rounded to 7%) of total web and app users access video monthly, but this seems to be positively related to brand loyalty as evidenced by much higher rates of usage among Guardian app users.

Although only a relatively small proportion of website users access video on news websites, the figure for video watching is growing, particularly off-site. On theguardian.com, the number of video starts grew by 45% between May 2015 and May 2016 with a 58% increase in video completes. 5 Facebook views (defined at three seconds) increased 136% between September 2015 and May 2016.

Off-site analytics

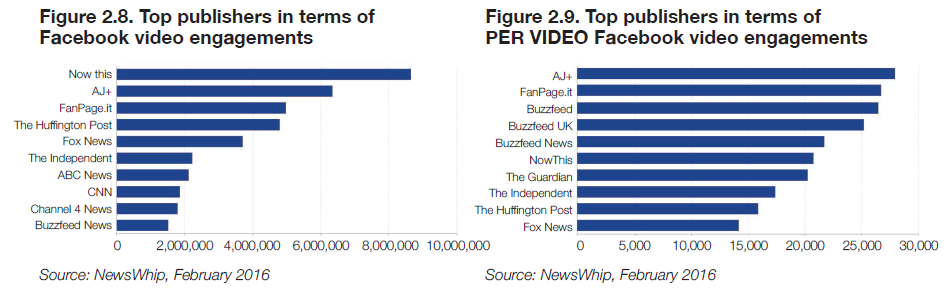

To identify which publishers fare better in off-site video consumption, we compared the Facebook engagement numbers (an aggregate number of Facebook likes, comments, and shares for each story) from the biggest UK, US, German, and Italian print, broadcaster, and digital-born outlets for February 2016. 6 We only included outlets that cover hard news though they may also have had other formats. The list of the top videos was provided by Newswhip, a company providing analytics on the way stories spread in social media. the results show that digital-born outlets like Nowthis, AJ+, and Fanpage tend to dominate Facebook video, while some broadcasters and print outlets like ABC News, Fox News, and the independent are also successful. However, we should note that if we included the UK entertainment publisher The Lad Bible in these charts, we would see that it would have almost doubled the Facebook engagements per video than the top news publisher (AJ+). Non-news BuzzFeed channels like Tasty (food) and Nifty (DIY) also generate far higher levels of engagement. These findings highlight the uneven relationship between news videos and those focusing on lifestyle or entertainment.

What videos work best in social media?

To understand more about the drivers of success, we analysed the 500 native Facebook videos that had the highest total engagement numbers (likes, comments, shares) from the same publishers for February 2016.

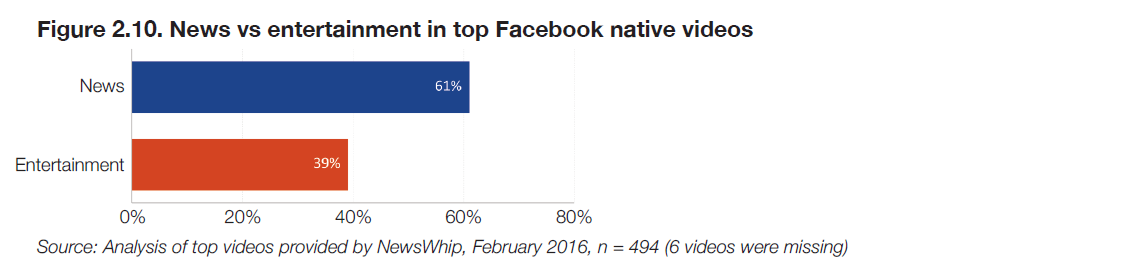

Genre and length

Our analysis showed that almost 40% of the most successful videos from our news brands related to lifestyle or entertainment content (for instance about animals, babies, or cooking) rather than harder news subjects such as current affairs, politics, science, or the environment. Four of the top ten videos related to entertainment or lifestyle content.

Even for brands associated with hard news like The Telegraph, The Guardian, or The Independent, their top or second videos in terms of Facebook engagement numbers turned out to be animal videos.

The average length for the Facebook native news videos was 75 seconds. However, 8% of the news videos were longer than 120 seconds and over half (56%) of the news videos were shorter than a minute. 7

Emotions

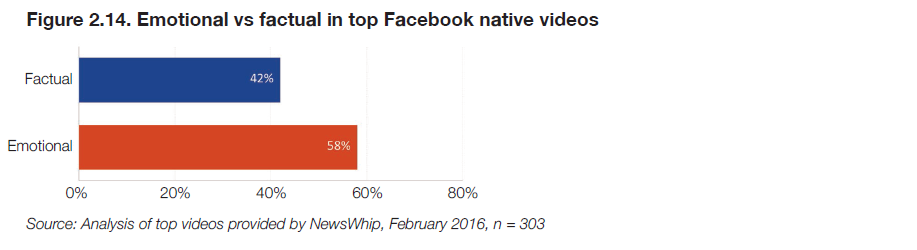

Next, we examined whether the videos were emotional or factual. While these categories are not mutually exclusive (emotional news videos usually have facts and factual videos can convey emotions), we were interested in whether they were primarily emotional or factual. In detail, the videos were coded according to whether ‘the primary purpose of the video was to convey emotional responses or to present factual information’. 8 Out of the news videos, 42% were primarily emotional while 58% were primarily factual. In the top ten native Facebook news videos in terms of engagement, seven were primarily emotional while three were primarily factual. the top emotional videos for February 2016 were a touching CNN video of a mother who listens to her son’s heart beating through the transplant recipient’s body and an ABC video capturing the reaction of a 106-year-old woman visiting the white House for Black History Month.

The top non-emotional video in terms of engagement was a video from the Huffington Post about an ocean clean-up initiative.

The role of emotional storytelling

Nowthis is a digital-born publisher that sets out to use emotion to create views and shares. According to executive editor Sarah Frank, ‘emotion is a wonderful starting point for your video’. Frank tells the story of a video they made about when only female senators showed up to work in congress after a snowstorm. Instead of just running a simple clip from CSPAN, the producer turned it into a riff on strong women, starting with a quote from one of the senators – ‘look around, isn’t this fabulous?’ – but then intercutting with inspirational gifs of Beyoncé and Oprah Winfrey. The result was a video that demanded to be shared and which delivered 60 million views in a week.

At NowThis, producers look for an emotional angle to drive the narrative of almost every video because sharing and liking means it is more likely to be picked up by the Facebook algorithm. This raises questions about whether social video with an emotional slant may ultimately change the nature of news itself. Sarah Frank accepts there is a danger of a slippery slope where only positive and partial news becomes visible in news feeds, but says as a young brand they are still working out how to manage these tensions: ‘we have examples where we feel like we’ve been objective and fair, but also drove emotion, had a really strong point of view and entertained people. 9

Made for online use or using TV content?

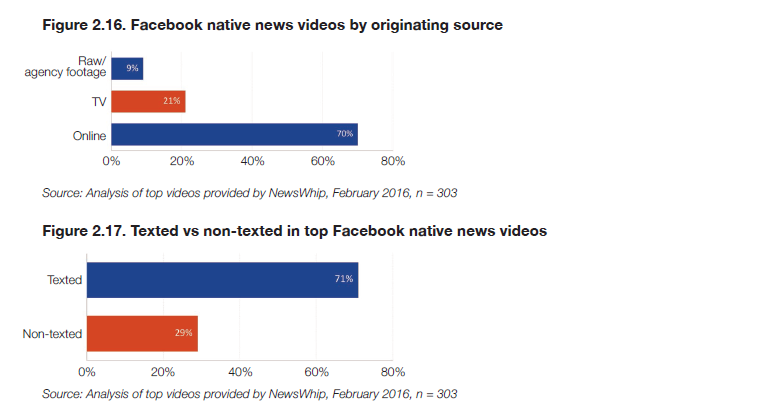

In our content analysis, the vast majority of the top online news videos were created specifically for online use. A small minority of videos were taken directly from television and used directly on Facebook without versioning. An even smaller share came from raw agency material or user- generated content. The majority of videos (71%) had a text overlay (like a giant subtitle) so they could be easily understood without sound.

We also coded the top 140 news videos according to differences in the sound. The categories were a) a reporter narrating the story, b) the video going straight to a politician or an interviewee, and c) the video having no one narrating but with music, natural sound, or no sound at all. The most striking result was that just 13% of videos were narrated by a journalist. The majority (51%) of the most successful videos had someone narrating or simply talking (usually a politician or the main actor of the story) and in 36% of the videos, there was no human sound.

Paris attacks: BBC video analysis

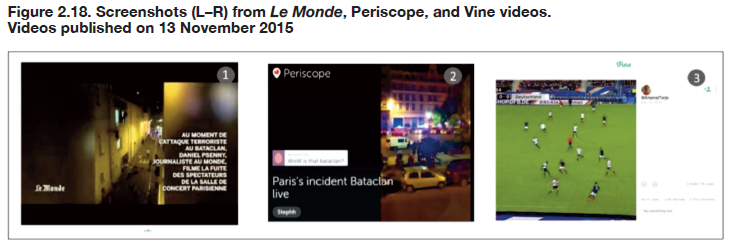

On the evening of 13 November 2015, a series of co-ordinated terrorist attacks took place in Paris and its northern suburb, Saint-Denis. Three suicide bombers struck near the Stade de France, followed by suicide bombings and mass shootings at cafés, restaurants, and a music venue in central Paris. The attackers killed 130 people, including 89 at the Bataclan Theatre. The timing of the event (Friday night) meant that many people heard the news first on smartphones and through social media rather than radio or TV. Eyewitness news came first from social media where new tools like Periscope added live user-generated video to the mix for the first time. Bystander Stephane Hannache used the app to broadcast live from outside the Bataclan, at one stage attracting around 10,000 simultaneous viewers. A Vine video from the football match at the Stade de France – with clearly audible explosions – was one of the first verified accounts of the attacks.

Daniel Psenny, a journalist for Le Monde, filmed concert-goers fleeing from the Bataclan from his flat on his iPhone. The dramatic footage was posted on social media and re-used by websites and television worldwide. These videos shot using mobile phones – often vertical or square in aspect ratio – defined the early stages of coverage long before professional television cameras were able to get to the scene.

Within hours, teams of journalists descended on Paris providing wall-to-wall coverage on radio, TV, print, and through websites. Video coverage played a key role and in the next section we explore how one major news provider deployed video on its news website and through social media.

The case of the BBC

During the Paris attacks, the BBC’s newsgathering operation was servicing two 24-hour tv news channels, two continuous news radio channels, and its well-regarded online news operation. In terms of online audiences, the day of the attacks was the highest-ever traffic day online for the BBC with video playing a prominent part. So what was the BBC trying to do and how effective was its online video output?

Production

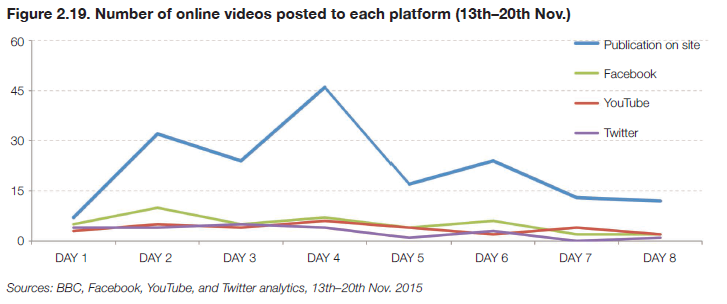

The BBC published 175 pieces of on-demand video about the Paris attacks on its own website in the week beginning 13 November 2015. It also live-streamed its TV and radio output throughout the event. We do not have the numbers for the live-streaming, only for on-demand video content. On social media, the BBC posted 41 Facebook video clips over the same period, 22 clips on Twitter using Twitter native player, and 31 clips on YouTube.

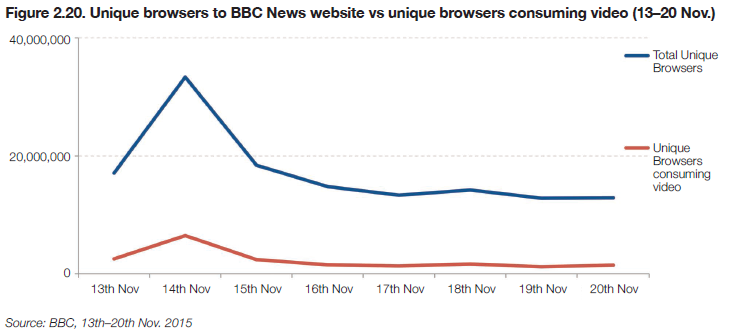

Consumption

As we saw previously in this chapter, on a typical day 11% of unique browsers on the BBC website or app watch a video. For the day following the attacks (14 November 2015), the share of users watching video almost doubled to 19% on the website and 22% via the BBC News app. This one- day peak was not related to the volume of clips produced, since this was higher on subsequent days, but rather it was due to the compelling nature of the video footage itself. It seems that video is a more important part of the mix in the first 24 hours of a big breaking news story.

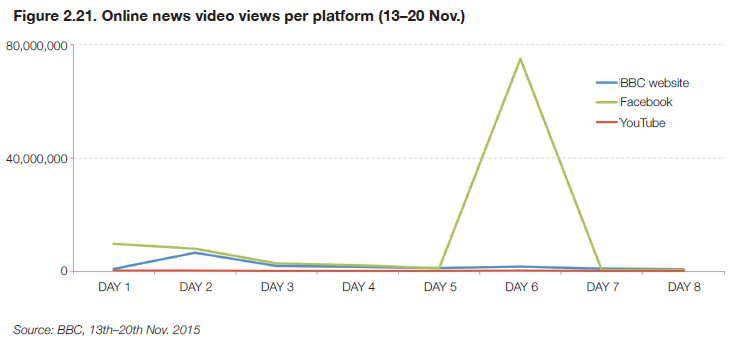

Breaking down these video views further, we can see that the majority of consumption (99 million views) came via Facebook with 15 million on the BBC site and about 2 million views on YouTube. We don’t have reliable figures for Twitter, though we can see the most viewed and shared videos. However, it is important to note that most of the Facebook traffic (72 million views) came from a single viral video and this distorts the overall picture.

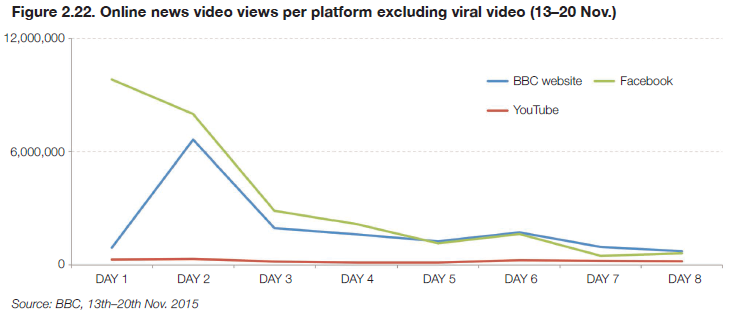

Taking out this single video, we can see the underlying story more clearly. Figure 2.22 shows how Facebook delivered ten times as many video views as the BBC on the night of the actual attacks but then settled down to delivering about the same number of views as on-site. This confirms research that shows that social media tends to be the most important destination in the first hours of a dramatic news story with attention then switching to websites for more considered analysis and context.

In terms of viewing time, the average length of a clip was three minutes and since the average watch is 50% (90 seconds) of the overall video, that gives a total of 22.5 million minutes on the website. This is compared with 54 million minutes for one clip on Facebook and 10.8 million minutes for everything else. The average view time on Facebook was 25 seconds, which is about a third of that achieved on the BBC site.

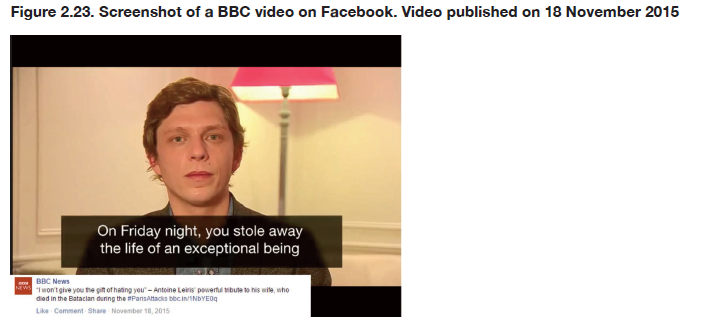

Viral videos

As previously mentioned, one viral video provided more video views than the rest of the coverage put together. This was inspired by a Facebook message to the IS killers from Antoine Leiris, husband of the one of the victims. The BBC reworked the post into a 90-second video made for mobile video with subtitles and music.

With 72 million views, 4 million likes, 1.5 million shares, and 300,000 comments, the video quickly pushed into Facebook’s algorithm and into everyone’s feed, the number of interactions helping to trigger the so-called viral effect (Digiday, 2015a). The post also did well on the BBC site (600,000 views) and on YouTube, but the Facebook effect was by far the strongest. according to the BBC’s digital director James Montgomery, ‘People were in some way responding emotionally … sharing it out of empathy. […] it was bound to draw interest, but I think the repackaging for mobile definitely helped.’ 10

It is worth noting that the average Facebook viewer watched only one-third of the video while the average BBC and YouTube viewer watched around three-quarters.

Which type of video worked?

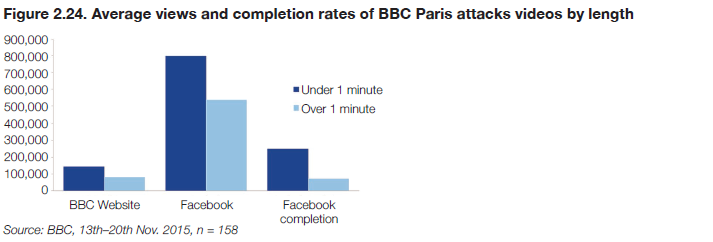

Content analysis of all on-site and Facebook videos revealed some interesting insights into which types of videos worked on-site and off-site in terms of length. 11 Confirming our earlier findings, videos that are shorter than one minute had more views both off-site and on-site (on average).

Overview of results

By using all these data sources, we can see that online news video is still a minority activity, especially on-site. While the share of users watching video on-site is relatively low, its importance increases significantly during breaking news events. Chartbeat data show that 97.5% of time spent on ten news publishers’ websites is still focused around text. Survey results also show that there is a widespread preference for text, with video voiders citing the desire for control as well as technological and advertising barriers. Off-site video tends to be watched more in countries with high social media news use and by younger groups. The type of video that is consumed off-site is short, emotional, and texted. The vast majority of videos on the BBC Paris case were not watched to the end when viewed on Facebook. Our content analysis showed that even among news publishers, a significant proportion of the most successful Facebook videos relate to entertainment or lifestyle. Videos that usually work in breaking news situations are also short and have no narration or anyone talking about the story. These findings bring us to the next chapters that examine how different publishers draw their production and monetisation strategies for on-site and platform-distributed video.

Production and distribution strategies

As already noted, online video is an increasing focus for news organisations as they look to increase engagement and drive new revenues. But how are news organisations adapting to the demands of online video in terms of production and distribution? In this chapter, we highlight the challenges and opportunities faced by three types of news outlet: broadcasters, legacy print outlets, and digital-born players. The analysis is drawn from more than 30 interviews with news executives and heads of video departments. The case studies featured have been chosen to reflect a variety of perspectives and to be indicative of the news industry, but of course they do not capture every possible scenario. Some organisations that are not mentioned in this chapter are highlighted in the following chapter on monetisation. All the discussions have helped us gain a clearer understanding of the range of production and distribution strategies being used.

Newspapers

Early newspaper investment focused on producing tv-style programming rather than adopting a native approach to online video. The Washington Post, The New York Times, Spiegel, The Wall Street Journal, and The Financial Times set up TV studios and many launched regular video shows and broadcast programmes. ‘At the beginning, we just made the mistake everybody does with that: we just took TVand put it into the internet, but it doesn’t work like that,’ admits Sven Christian. 12 from Spiegel. Most newspapers have since changed strategy, with the majority downplaying TV-style production for a broader set of approaches that encompass short-form news, social video, documentaries, and immersive storytelling such as virtual reality (VR).

Significant challenges have emerged around the hiring of journalists with the right skills, the organisation of teams, and around the need to adapt the newsroom workflow to include video in the commissioning process right from the start. The Telegraph, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, Die Welt, and The Economist represent how differently legacy print organisations engage with the challenges of learning to create, package, and distribute news video.

The Telegraph (UK)

A team of about eight journalists provide the website with a steady stream of news videos each day. They are not traditional journalists you might find in a broadcast newsroom; rather, they are multi-skilled producers and editors using off-the-shelf software packages like Adobe Premiere. They have developed a series of distinctive native formats, ways of packaging video that can be repeated efficiently and these can be summed up as follows:

- In 60 seconds

- In quotes

- How the internet reacted

- By numbers

These heavily templated formats allow each video to be created in as little as 20 minutes but also allow journalists to focus on the content itself. Throughout the day, a video news editor is in charge of selecting and commissioning stories and overseeing the producers, acting as the link between the video department and the rest of the editorial team. In recent months, there has been much more focus on social video and on Facebook in particular. Beyond news, The Telegraph is looking to develop lifestyle content in motoring, art, fashion, beauty, and technology, with a separate team producing sponsored content for brands. The idea is to build a business worth £10 million within three years (The Media Briefing, 2015). ‘I think the key is next year and beyond will be about accelerating away from tv and thinking really clearly about what defines us from television news,’ says Head of Video, Edward Adams, who was recruited from broadcaster ITV. ‘How do we make stuff really stand out as telegraph content rather than any other content.’ 13

The Guardian (UK, US and Australia)

The Guardian runs a team of more than 30 people working in London, New York and Sydney, reflecting new editor Kath Viner’s strong interest in developing new forms of storytelling. The heart of the operation is providing news to illustrate and embed in web pages: ‘everyone at the bare minimum expects video now,’ says Christian Bennett, the Guardian’s Global Head of Video. ‘If David Cameron says something, people want to see David Cameron saying that and judge for themselves how he said that.’ Beyond news, which is largely sourced from agencies, the team produces one or two explainers each day and then original features that might involve Guardian journalists shooting footage and take more time and resources. recent examples include a series on politics beyond the Westminster bubble by John Harries and John Domokos and Shakespeare solos, beautifully shot extracts from plays, read by famous actors. These may not make money but do help build an identity that matches the values of the wider brand.

Off-site social video is also an increasingly important part of the mix, although The Guardian has found that each platform requires a different approach. Columnist Owen Jones has a hugely successful YouTube channel where he runs long and often personal videos as well as having conversations with fans and subscribers. Facebook requires a different approach again, where videos need to be shorter, more attention grabbing and more playful: ‘we’ve even had conversations … about how videos offsite have to be louder than onsite ’cause it’s just a more noisy place’, says Bennett.

The Wall Street Journal (USA/international)

The video team at The Wall Street Journal is fully embedded with reporting desks in New York, San Francisco, Washington, Hong Kong, and London. The team has video journalists as well as video editors and producers. Wall Street Journal reporters who find themselves in a breaking news situation are expected to shoot video directly from their phones, but in most cases the video desk works on a planned schedule. In terms of formats, short videos are among those that work best for The Wall Street Journal. ‘We’ve gotten away from long-form documentary style storytelling,’ says global Head of Video, Andy Regal. ‘In the digital space, we find that people are more inclined to want to be seeing things in shorter durations.’ 14 The Wall Street Journal video content is distributed among more than 30 platforms with all content on-site in front of the paywall because of the higher advertising premiums. The paper has recently been experimenting with different formats and it was the first US newspaper to join Snapchat Discover in January 2016. The Wall Street Journal is among those organisations that saw the potential of video early and has made a strategic and long-term investment.

The Washington Post (USA)

PostTV was an early foray into video in 2013 with a live channel that aimed to be the ‘eSPN of politics’ (Calderone, 2013). With the project burning cash and failing to meet targets, The Washington Post pivoted its strategy in September 2015, rebranding its efforts Washington Post video and investing in shorter content for various platforms while abandoning the long-form shows. The new Washington Post video team, led by Micah Gelman, consists of 40 people, all embedded in different newsroom sections and part of the commissioning process of a story from the start. Ten of them are video reporters who go out on assignment, with the rest managers and video editors. The team produces content customised for each of the different platforms they are on. Stories for Facebook, for example, have text overlay and are designed to work without sound. ‘We are thinking of each platform as a unique ecosystem and not trying to force one type of content down the line,’ says Gelman. 15

Die Welt (Germany)

In December 2013, the German media group Axel Springer acquired the 24-hour television news channel N24 with the aim of integrating with the Die Welt news website as a multimedia powerhouse (Axel Springer, 2013). Despite still being separate teams, the web video units at N24 and Die Welt work closely together. Antje Lorenz at N24 runs a team of six people (four editors and two freelancers) while Oliver Rasche’s team at Die Welt has eight permanent staff plus five freelancers and is tasked with publishing online news video on all of Die Welt’s platforms. N24 is not the only source of video content for Die Welt, Rasche explains, but it is definitely the most important one. 16 Multimedia producers curate the full process of the publication of online videos, from editing to adding headlines and text: ‘this is a kind of job we didn’t have before. It’s completely new and they are developing or defining their role in a whole new way,’ says Antje Lorenz. Each morning, Rasche and Lorenz get together and plan their digital coverage for the day, keeping an eye on what is trending on social media and optimising the content for each platform. The strategic importance of video at Die Welt is reflected in the role it plays in its internal analytics system (Cherubini and Nielsen, 2016). The outlet has devised an ‘article score’ by which all published articles are ranked. the score is made up of five criteria: pageviews, time spent on the article page, video views, social shares, and bounce rate.

The Economist (international weekly news magazine)

The Economist has been experimenting with video for many years, but has only recently found a strategy that works from an editorial and commercial point of view. One key question for executives was whether video should be a complementary ‘side-salad’ to the text article or a ‘video-version’ of it. Eventually they realised it doesn’t have to be either: ‘it doesn’t have to be related to the print product in any way,’ says deputy editor, Tom Standage. ‘It doesn’t have to be derived from it. It can just be what it is. So the first thing was breaking the link with the weekly [newspaper].’ 17 Now, there is a single video unit which is a merger of the team behind Economist Films – 15-minute mini-documentaries with high production values – and a team focused on short explainers made for social media.

Another important aspect of The Economist’s approach to video was to find its own distinctive voice. Their video is presenter-less, global, comparative, data-driven, and with a little bit of humour. ‘If you put all those together, it feels like The Economist,’ says Standage. Over the next year, The Economist plans to produce VR documentaries and a daily video feature that will be two to five minutes long and will be branded Espresso TV (Swant, 2016).

Broadcasters

Broadcasters have access to video skills, equipment, and a considerable amount of content, including archive footage and trained video journalists on the ground. But the transition from broadcast to online video has not always been easy. The following cases of two UK (ITV News and the BBC) and two US broadcasters (Fox News and CNN) reflect the landscape of digital video in broadcasters that differ in size and output (with a domestic and global focus).

ITV News (UK)

The focus for online video at ITV News is to move away from pushing television packages online and instead to create more immediate and authentic mobile video: ‘television packages are fantastically polished, creative narratives that work for TV, but it doesn’t mean they’re going to work for online,’ says Head of Digital, Jason Mills. ‘Radio doesn’t work on TV. Newspapers don’t work on radio. It’s just a whole new model, really.’ 18 At ITV News, social and mobile-friendly videos are created by social video producers. Their main job is to take a couple of the main stories of the day from the TV channel and turn them into 30 to 40-second videos, as well as to monitor trending stories that may work online-only. They are also experimenting with correspondents filming directly on mobile phones, either putting them out raw – through Facebook Live and Periscope – or adding simple infographics. Alongside Facebook, ITV News also produces video stories for Instagram and occasionally for Twitter. The length of all these stories varies according to the platform: 15 seconds for Instagram, 20 to 25 seconds for Twitter, and anything up to a minute for Facebook. Story selection will also vary with fun, soft stories working better on instagram than serious news, Mills explained. ITV News’ social strategy at the moment focuses on engagement and brand extension, rather than direct monetisation.

Fox News (USA)

The key focus is to reuse existing TV content with the vast majority of videos posted online (90%) taken from the Fox News channel or Fox Business Network, with the remaining 10% of original content produced specifically for digital: ‘we have this great repository of what is possibly considered the greatest cable news network in the country, and to not use that content would almost be a sin,’ Director of Digital Video Operations, Brian Korner explains in an interview. 19 TV segments or debates tend to be cut up into longer chunks (90%), whereas the original online content (10%) is shorter and focuses more on softer news like leisure and lifestyle pieces or food-related topics. In addition, the mobile/social media video tends to be different from desktop:

We find that there’s kind of a sweet spot in about a five-minute clip for browser-based. When you go to mobile-based, or social media-based, the sweet spot gets a lot shorter. In the case of Twitter or Facebook apps, you’ve got seconds to engage them, and then hopefully you can keep them around for two minutes. But that’s about what you’ve got. 20

Korner sees a future that combines appointment-to-view television bulletins with ‘an anchor sitting at the desk’ with a much more tailored video on-demand service delivered through apps and online media. ‘I think the future of all online video is on-demand. People want it when they want it.’ He believes that time-shifted programmes (VOD) from Fox News personalities such as Megyn Kelly will be the future for Fox News digital video.

CNN (US and global news network)

At CNN digital, Ryan Smith, Supervising Producer for digital video, looks after the international arm of the digital video business. His team of editors, video journalists, and producers select, edit, and produce content to be posted online and distributed via all CNN digital platforms. They are multi-skilled journalists who can shoot videos and write scripts, as well as edit them. The team operates in close co-operation with TV, not only selecting the most appropriate content from the 24-hour channel and tailoring to the web, but also participating in the commissioning process: ‘a lot of the time I give guidance to correspondents and producers going out into the field to try and make their video as friendly to those other formats as possible,’ Smith explains. 21 While CNN has a great brand, a key internal challenge, he says, is to change the mindset from being a traditional television-based organisation to a television and digital-based one. At CNN digital, online video is versioned for desktop, mobile, and social: ‘the way you consume your news is very different on every screen to me, and I think this is where the industry is going now. Before, we considered digital video as one video and made a video that fitted all, hopefully all devices. Now we’re trying to break that down a little bit.’ 22

CNN desktop video is designed to complement text. Smith says the sweet spot for desktop videos is around 90 seconds in terms of completion rates. By contrast, mobile video tends to be half that length and needs to work in a standalone context. Social video is treated differently again because of the highly competitive context of a Facebook feed. ‘It’s going to autoplay, so what you need to do is you need to get straight into something impactful.’ 23

BBC (UK and global news network)

The BBC has one of the largest video newsgathering operations in the world, so it is not surprising that it is looking to capitalise on its experience with moving pictures. as with other broadcasters though, the key challenge may be to break away from a broadcast mentality, as digital director for BBC News James Montgomery explains:

The BBC used to take the broadcast output, cut it into small pieces and sprinkle it somewhat randomly on digital platforms. We know now, particularly because of the rise of mobile, which stretches the difference between the television experience and the primary digital experience, that’s not really enough. 24

One of the most significant new initiatives of 2016 relates to the creation of a new mobile video experience, initially for the BBC News app, called Ten to Watch. Inspired by Snapchat and Twitter Moments, it features vertical video, texted video, and much shorter durations. ‘There is an interesting study,’ says Montgomery, ‘that [shows that] people actually absorb information more quickly on a mobile phone because they’re concentrating a bit more. So they can get through it faster. Duration absolutely matters because broadly speaking, shorter is better. Although I sometimes caveat it, ultimately it’s not really about duration, it’s about how long you can hold the user’s attention.’ 25 Editorial project lead Nathalie Malinarich says the BBC is still learning about what works with mobile video: ‘People aren’t sitting at home thinking I’m going to spend an hour in front of the TV. You need to hook them in straightaway, your storytelling needs to be very tight.’ 26

Beyond mobile video, the BBC continues to experiment with social video to reach out to audiences not prepared to come to the website itself. It has pioneered new short-form videos for networks like instagram, vine, and line, while the BBC trending brand looks to source and distribute stories through social media. A key issue now is to improve legacy technology systems to make it quicker to move video assets from broadcast to the website, not just in English but also through its output in almost 30 languages.

Pure players

Pure players

Digital-born outlets are not burdened by legacy, and with a high propensity to take risk as they try to break into a very competitive market, some of them are playing a leading role in both video format and business model innovation. Of all the digital players, BuzzFeed has so far made the most impact and some of the biggest investments. Hundreds of video producers work at the BuzzFeed Motion Picture Studios in Los Angeles where they have been perfecting long and short-form video formats that demand to be shared. With a culture oriented towards endless experimentation, BuzzFeed has innovated around news and launched new lifestyle channels such as Tasty, a cooking channel, which was the number one video publisher on Facebook in October 2015 with 1 billion views (Marketingland, 2015). BuzzFeed is also moving into long-form content and television, as is the youth-oriented media company vice, which plans to launch 20 tv channels across the world in 2016 along with six more digital networks (Spangler, 2016). At the same time, it is important to separate these initiatives, which are largely focused on lifestyle content from news itself. For this study, we focused on our interviews with AJ+, Fanpage, and NowThis, three of the most innovative companies working with news and factual content. These cases reflect two organisations (AJ+ and NowThis) that are almost exclusively occupied with online news videos, and Fanpage, a successful Italian digital-born news organisation.

AJ+ (US-based youth-focused network)

Many of our interviewees cited AJ+, founded in September 2014, as a source of inspiration when it comes to online video. AJ+ is a digital spin-off from Al Jazeera, focusing on building audiences through social platforms rather than investing in their own apps and websites. The content is created to be short, shareable, and mobile-first. By January 2016, AJ+ employed 70 people in their content team producing around 50 videos a week, most of which are around a minute long or less (Digiday, 2015b). Through Facebook alone, AJ+ delivered 2.2 billion video views in 2015, around half of which were 30-second views. They currently produce between ten and 12 videos a day for Facebook: ‘we are creating content for each individual platform and thinking about the user experience in each platform, based on [the fact] that it optimises the product and the experience,’ explained executive Producer, Michael Shagoury. 27 All the videos produced by AJ+ come from a mix of agency footage, original material, and user-generated content.

Fanpage (Italy)

In Italy, legacy print media companies have traditionally held the lion’s share in the online market through their digital offshoots. When it comes to social presence though, a pure player like Fanpage.it, with its more than 5 million followers on Facebook, is clearly ahead of the game with over twice the figures of the two main news organisations Corriere Della Sera and Repubblica. Fanpage focuses mainly on entertainment videos and soft news, but it also covers breaking news and more serious topics like the problem of toxic waste in the region around Naples. The common point of all their coverage is always trying to maintain Fanpage’s tone of voice. ‘[in our coverage] We’re really trying to make something that’s unique,’ explains editor-in-chief, Francesco Piccinini. 28 During the demonstrations against same-sex civil partnerships, held in Italy in January 2016, Fanpage created a video in which it asked rally participants provocative questions about homophobia, and edited them together in a humorous way, leading to more than 4 million views overall. Video reporters at Fanpage are responsible for producing the entire product, i.e. shooting as well as editing their own videos. The site has a dedicated video team for Facebook and also distributes content via YouTube, Instagram, Twitter, and Google+.

NowThis (US-based)

Another outlet frequently mentioned as an example of best practice in online video is NowThis, another distributed news company. The company’s vision statement states this: ‘Homepage. Even the word sounds old. We bring the news to your social feed.’ Ashish Patel, Senior VP of social media, explained in an interview 29 That the editorial strategy starts with understanding the specifics of the audience on each platform. NowThis organises workflow around platform experts, hired to match the platform’s audience profile and in total they produce between 50 and 60 pieces of content per day. Stories are selected and packaged differently for each network. For example, Patel explained that hard news stories or breaking news don’t do well on Instagram, while world news is surprisingly popular via Snapchat, which has the youngest demographic. Speaking at a journalism conference, Newsrewired, in March 2016, Patel identified four key criteria for a successful social video strategy: 1) create videos that don’t require audio; they should default to mute; 2) ensure that the first five seconds are compelling, especially given that 70% of the people are on mobile; 3) look at and learn from key data points, such as completion rates and the worst-performing stories, rather than trying to replicate viral hits; and 4) remember that emotion drives the video shares (Newsrewired.com, 2016).

Strategic and organisational challenge

The three types of outlets analysed – newspapers, broadcasters, and pure players – all come from different perspectives, bear different legacies, and face different challenges. What newspapers and pure players have in common is that they are both new to video and therefore need to build capacity and skills from scratch. Digital-born companies have generally had access to capital funding to invest, whereas newspapers, in a period of retrenchment, have found it far more challenging to find new money. Broadcasters should be in the best position to take advantage of the move to video with a wealth of relevant skills and footage at their disposal, but in many cases we find them struggling to adapt to the new grammar of digital online video. They are under pressure to maximise the impact of their existing investments, hence the focus in interviews on re-versioning TV. As many of our interviewees have pointed out, this presents a significant cultural challenge which leaves them open to disruption from competitors better able to take risks about new formats and new forms of social distribution.

In terms of organisation and resources, it is hard to define a clear pattern given the range of experimentation and the fast rate of change. Many news organisations start their journey by hiring one or two video specialists as a response to an emerging opportunity. This often develops into a specific team with responsibility to develop best practice, though this team is often isolated and operates independently from the rest of the newsroom. At a later stage, once value is proved, strategic investments are made in online video technology with journalists trained in mobile video and new storytelling techniques. For a few news organisations, the strategy is clearly articulated from the top and is connected to the wider mission and business models. At The New York Times, Mark Thompson made video an important part of the strategy soon after his arrival as CEO, while James Harding at the BBC has personally championed the ten to watch mobile video project. Leadership has also been a key factor at the Wall Street Journal: ‘credit goes to the highest-ups here, including our editor-in-chief Gerry Baker, who saw video for what it was a number of years ago,’ says Head of Video, Andy Regal, who says this helped give the Wall Street Journal a head start: ‘video is a fully integrated, fully realised aspect of the journalism conducted here.’ 30 Many digital-born companies, like BuzzFeed, moved rapidly into video following a series of experiments but underwent the same kind of process with a separate video team before integrating learning throughout the organisation (Küng, 2015).

Producing in multiple formats: ‘it’s expensive to be everywhere’

One common theme which came up in interviews with different types of media company is that a ‘one size fits all video’ is no longer an option. There is recognition that each platform requires a different approach even if it is often hard to deliver in an efficient manner. ‘It is expensive to be everywhere,’ says Dr Yaser Bishr, executive director of Strategy and corporate development at Al Jazeera Media Network, 31 pointing out that each network requires a different length or a different treatment. Al Jazeera is actively looking into technologies and companies that can simplify workflow and reduce cost. Organisations like the BBC are also finding a real problem in quickly and efficiently delivering more broadcast content online with the necessary metadata so it can be easily found and shared. Print organisations unable to invest in a large production team are also looking to find better technology solutions to simplify the process. The Italian regional publishing house of Gruppo L’espresso uses software from Wochit to produce a large number of videos each day with a relative small investment in terms of resources. The software lets you use copyright-cleared content from news agencies like reuters, as well as upload your own content to the platform.

Photos or videos are packaged, in a mix of automation and human curation, and animated by the software, which also lets you add graphics and the organisation’s logo. Meanwhile, an efficient and sophisticated content management system has been at the heart of the success of digital-born NowThis. The Switchboard system allows producers to assemble footage semi-automatically, publish the content directly onto social feeds, and includes predictive analytics to drive future coverage. An insights team monitors how videos perform and feeds data back to producers and editors. While all media companies are looking to make production more efficient, it is digital-born outlets that tend to place technology and data at the heart of their strategies, focusing on in-house solutions to provide competitive advantage. Traditional providers tend to focus on third-party technical solutions, looking more to journalistic talent, creativity, and heritage to create distinctiveness.

Overall we find that some of the most successful organisations in the video arena tend to have the following key characteristics: 1) clear, focused strategies and a leadership that is committed to video; 2) investment in native online video skills and strong support for creativity and innovation within those teams; and 3) investment in appropriate technology, tools, and efficient workflow to support those teams and strategies.

Future developments

Across the board, we see a considerable degree of consensus – and focus – around the importance of short-form social and mobile video, but such is the speed of change it is quite possible this will look very different in a year’s time. At the same time as brands like the Huffington Post were abandoning live streaming coverage at the beginning of the year, Facebook stepped up its efforts around ‘live video’. Once again, publishers are now being encouraged, in some cases paid, to create live experiences. Facebook says that live broadcasts attract ten times more comments than regular videos, but it is not clear how long this will last (Newswhip, 2016). There is a clear risk that news organisations will end up overly dependent on platforms and changes to their strategies, which they are unable to influence.

In this respect, it is interesting to note that while some publishers like NowThis are concentrating on scale in distributed media, others like The Economist, The New York Times and The Guardian are pursuing distinctiveness. The New York Times has been focusing on long-form series, such as the ‘Fine line’ about Olympic athletes and the ‘inside track’, which interviews pop stars about how their hit songs were created. It has been a pioneer of VR, distributing Google Cardboard viewers to around 1 million loyal subscribers. More recently, The Guardian has launched its first VR project, ‘6×9: a virtual experience of solitary confinement’, which takes readers into a US solitary confinement prison cell and tells the story of the psychological damage that can ensue from isolation (The Guardian, 2016). The Guardian created two versions of the project: the VR version is available through the Guardian VR app and a 360-degree video is available for people who don’t have VR headsets (Bilton, 2016). These investments are not for the faint-hearted with partnerships and major sponsorships the order of the day. The video landscape becomes more complex and more expensive with every passing day.

Monetisation strategies

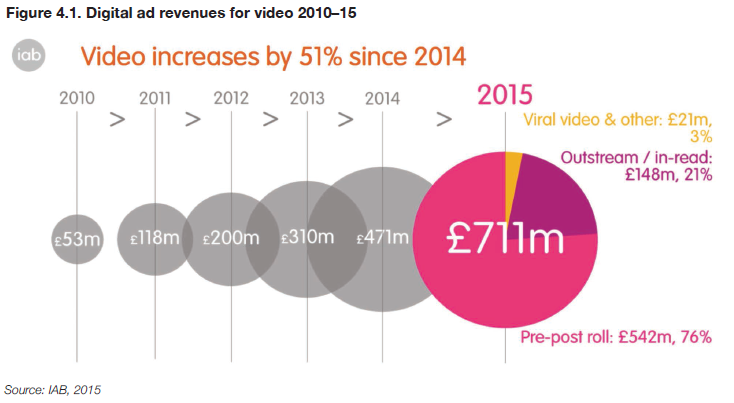

With the growing problems of display advertising around text, many media companies are looking at online video as a new way of driving revenues. The latest UK IAB statistics show that video ad spend is growing at 51% a year and now makes up almost a quarter (23%) of the total spend on display (IAB, 2015). In the USA, digital video ad revenue was 4.2 billion dollars in 2015, up 30% from 2014 (IAB, 2016). However, it is not clear that news will benefit to the same extent as the market in general, given 1) the often difficult subject matter; 2) consumer resistance to pre-roll advertising; and 3) the dependence of off-site monetisation on Silicon Valley product initiatives. It is not surprising then that many publishers are eyeing other models such as sponsorship or creating video production services for advertisers. For others still, the value of video is seen as more indirect, helping to market specific services or attract new customers to the brand.

Direct monetisation

According to IΑΒ data on UK video display, three-quarters (76%) of revenue in 2015 came from pre- and post-roll advertising, with most of the rest coming from new ‘outstream’ in-read formats that play video, for example between paragraphs of text (IAB, 2015).

However, publishers’ attitudes towards pre-roll advertising on online news videos are sharply divided. ‘We think that pre-roll is one of the crummiest innovations of digital video, and certainly not one that we wish to shower upon our readers,’ says Xana Antunes from Quartz: ‘Can you imagine a broadcaster forcing you to watch an ad every two and a half minutes? […] I am astonished to even find myself having that conversation sometimes.’ 32

These attitudes reveal larger differences in online news video strategies and the business models of different news organisations. Quartz, for example, took the decision to focus on sponsored content rather than display right from the beginning. For other publishers we interviewed, the objection was less about the form and more about the practical application. Publishers feel that while they have adapted their videos to the digital age, advertisers are lagging behind in adapting their creative: ‘The advertising business has not caught up yet with the changing nature of audience interaction,’ says Jason Mills at ITV News. ‘Where are the five-second pre-rolls?’ 33 Industry bodies like the IAB say advertisers are now responding with shorter formats, but CNN’s Ryan Smith says this is still not fast enough: ‘It can still be frustrating: a 30-second pre-roll on a one-minute video is not engaging for an audience. they’re going to look at it and think the juice isn’t worth the squeeze.’ 34

Many publishers recognise the damage pre-rolls may be doing but do not have the luxury to wait for alternatives to emerge. No one has yet come up with anything as compelling from an advertising perspective, says Alison Gow from Trinity Mirror: ‘What we know, right now, is that advertisers are happy with pre-rolls. It’s what they want. The consumer is fairly familiar with them.’ 35 Italian start-up Fanpage uses pre-rolls extensively and editor-in-chief Francesco Piccinini is unapologetic: ‘It is fair. broadcasters put three or four ads before the one o’clock news […] I can put it at the beginning of my video.’ 36

Despite this defiance, there are a number of reasons why pre-roll may not be sustainable in the long term. Firstly, CPMs (cost per thousand impressions) are likely to fall as supply of online video increases, though data from ad tech company Sizmek (see Figure 4.2) suggests this trend may already be underway, though there is still a clear premium over other forms of display such as banners.

A second reason for caution relates to the move towards off-site consumption. Facebook has ruled out the use of pre-roll ads in the news feed and is looking to encourage consumers to view a number of videos in a row (via its ‘suggested videos’ feature). Some ads will then be shown between videos, with revenues split between publishers and Facebook (Griffith, 2015). Although testing is still continuing and revenues are still relatively low, Mark Melling from AOL Europe suggests these are developments publishers cannot ignore:

Facebook isn’t going anywhere and we know that the monetisation will come. You could say the same thing about YouTube. You could say, ‘Well, YouTube didn’t have a monetisation strategy, why would you put video on there?’ And whoever didn’t do it got left out in the cold. 37

Many publishers are building their audience now on Facebook and other social platforms in the hope and belief that the money will come. as John Pullman from thompson reuters said, ‘(video on platforms) is the big issue of the industry today. Are we going to get money from Facebook and other platforms? It is something that occupies all our minds all the time.’ 38

But there are no guarantees, particularly given that success will require audiences to watch multiple videos using patterns that are not yet established. In turn, that requires enough compelling quality content which is why Facebook is currently encouraging, and in some cases paying, publishers to produce it. It remains to be seen if this is in the long-term interests of publishers.

Branded or sponsored content

An alternative path for monetisation in general has been the growth of branded and sponsored content, notably pursued by digital-born companies like BuzzFeed, Vice, and Quartz. BuzzFeed is heavily reliant on so-called ‘native advertising’ and 35% of these revenues now come from video, up from 15% in 2014 (Fast Company, 2016). This is set to grow further with Facebook recently announcing that it would allow native video ads from publishers labelled with a ‘sponsored by’ message (Digiday, 2016). Traditional media companies such as The Guardian and The New York Times have also been investing in creating content for brands with G-Labs and T-Brand Studios respectively. Video is becoming an increasingly important part of these propositions according to Anna Watkins, Managing Director of G-Labs (The Drum, 2016):

Increasingly [we are] distributing our content off-platform, whether that’s Facebook Instant Articles, whether that’s AOL On, whether that’s any of the other big tech players. So clearly, that therefore means the formats are changing. There’s much more of an investment in video.

Branded content, which is often made by a media company but where the advertiser has editorial control, can be distinguished from sponsored content where control normally remains with the publisher. The Economist is one publisher that has embraced the latter route. As deputy editor Tom Standage explains, at The Economist it is always the editorial team that comes up with ideas for videos they want to make and the sales team then pitches these ideas to sponsors:

We pre-approve a menu [of videos], and the order in which we make the things on themenu depends on the availability of sponsorship, but the sponsors don’t get to choose the topics. There is no brand video […] Branded video is not journalism. It’s fine to do it, but it’s just no longer editorial, it’s no longer journalism. 39

Two recent examples of brands supporting sponsored video in The Economist are Turkish Airlines, who signed up to sponsor a travel series called Passport, and Ernst and Young, who will sponsor a business series called The Disruptors.

Publishers going down the branded content route include Fanpage, the first outlet to do branded video advertising in Italy, and NowThis, a AS-based digital-born video outlet, which is primarily monetised through branded content. At NowThis, these videos are created by a team that sits separately from their editorial team, and the content is distributed over their channels as well as through the channels belonging to the brand itself.

It is still early days, but one problem with relying too much on native advertising may relate to scaling. Publishers we talked to emphasised the high cost of creating unique branded videos, which by definition cannot be automated (and scaled) in the manner of a banner ad. It was recently reported that one of the reasons why BuzzFeed missed its 2015 revenue projections relates to problems scaling its native advertising business model, while NowThis is said to not be making a profit yet (Garrahan and Mance, 2016). Branded and sponsored videos demand a considerable amount of investment and they also put publishers in direct competition with advertisers (Herrman, 2016).

Marketing and referrals

In our interviews, the most widely cited reason for publishers to invest in online news video, especially off-site, is to engage people with their brand. As we saw in chapter 2, most online news video consumption occurs off-site, in social media and especially on Facebook. While native video on Facebook does not necessarily bring referrals back to the news website, successful videos can bring more likes and comments, which in turn means that more people will see their links in the future.

Other news organisations are using videos to cross-promote their products and services. Broadcasters like the BBC post marketing trailers to television and radio content while also using native video to engage hard-to-reach younger audiences with public service content such as news explainers. Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin creates short stylish Facebook video trailers for its weekly print publication using easy-to-use iMovie software and has had some success in driving print subscriptions. The Economist also sees the use of free video as a useful way of marketing its paid-for services: ‘we hope that people will become educated about our brand and our products and then subscribe. […] Posting free stuff on Facebook and Twitter is the only way to tell people what we do.’ 40

In one way or another, online video is becoming an important digital outrider for different business models. It can drive revenues through sponsorship or advertising, and be used to cross-promote other products or to feed a subscription funnel.

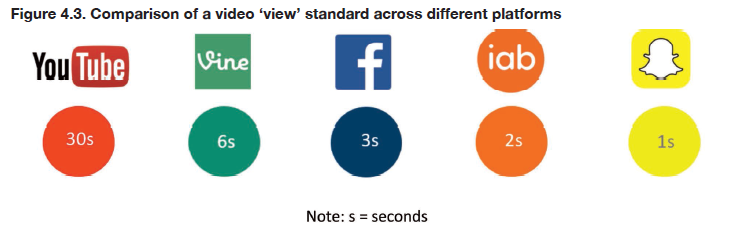

Metrics and viewability

One area that is holding back growth of online advertising has been confusion over how to measure and verify a view. Ad fraud affects video as much as other forms of display, and off-site platforms have different standards on how to measure a view. Facebook’s use of autoplay combined with a video view count of three seconds opens the possibility of a large number of inadvertent or disengaged plays. It also makes it hard for advertisers or publishers to compare performance with YouTube, which counts a play after approximately 30 seconds.

The difficulty in interpreting auto-playing Facebook views has meant that publishers are taking more notice of other metrics, such as engagement numbers, to measure success, as Xana Antunes from Quartz explains:

We find ourselves guessing how much of our audience meant to watch the video and how much of the audience found itself watching it. But [that becomes clear] when you start looking at metrics like Likes and Shares, which ultimately on Facebook are the determinant of whether something succeeds or not. 41

Other publishers have created dashboards which try to measure the level of engagement with content. These may include time spent or the percentage of a video that is viewed: ‘The key stat is the quality of a view,’ says Ben Sinden, director of video content at The Telegraph, where other indicators include retention rates and the number of videos watched in a session (The Media Briefing, 2015).

Virality: the new norm

A particular difficulty with trying to build a business on the basis of off-site social video is the unpredictable nature of consumption when compared with text and routine audiences in print and broadcasts.

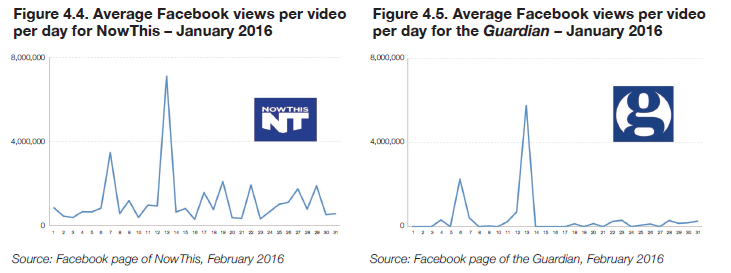

Our research into the Facebook video performance of two outlets – NowThis and The Guardian – shows that on some days, Facebook video consumption can be six or seven times higher than during an average day (see Figures 4.4 and 4.5). We counted the Facebook views per video per day in January 2016; all the views for each video were assigned to the day of publishing since there was no way to know how many views took place on subsequent days.

We could argue that the problems of virality also exist for text articles distributed through platforms like Facebook. However, research by Newswhip (republished in tables 4.1 and 4.2) shows that videos have much bigger peaks in terms of engagement. For publishers like the BBC, CNN, and Vox, the top five articles in terms of shares account for 2%, 4%, and 26% of the total shares, respectively. When it comes to the videos, the top ones account for 54%, 65%, and 76% of the total Facebook shares for videos. Viral videos are not new; they have been a feature of other platforms like YouTube for many years but the priortisation of video on Facebook and Twitter and the introduction of autoplay has increased the potential for accidental exposure.

These findings suggest a very different picture from the analogue world where TV bulletin ratings or newspaper circulations were rather stable and spikes of 600% were almost unimaginable. Chris Lunn, the BBC’s Senior Product Manager, video, argues that the aim is to get a predictable amount of video views per month for their international audience, and not rely on news spikes from a revenue point of view. 42 This is partly because spikes are often around sensitive news events that brands and publishers would not want to place an ad on anyway. Mark Melling, the director of video for AOL Europe, does not panic about dips and spikes, given the unpredictable nature of videos: ‘this is the new norm. and if something went viral today, it doesn’t mean it goes viral tomorrow.’ 43

These findings suggest a very different picture from the analogue world where TV bulletin ratings or newspaper circulations were rather stable and spikes of 600% were almost unimaginable. Chris Lunn, the BBC’s Senior Product Manager, video, argues that the aim is to get a predictable amount of video views per month for their international audience, and not rely on news spikes from a revenue point of view. 42 This is partly because spikes are often around sensitive news events that brands and publishers would not want to place an ad on anyway. Mark Melling, the director of video for AOL Europe, does not panic about dips and spikes, given the unpredictable nature of videos: ‘this is the new norm. and if something went viral today, it doesn’t mean it goes viral tomorrow.’ 43

At CNN, Ryan Smith agrees that spikes happen more often now, given the nature of the medium. but CNN pays close attention to these spikes since they see them as an opportunity for brand engagement:

I know roughly what my day-to-day audience is on an average day and I know when something is peaking as well. So when that happens, our strategy definitely changes to reflect the peak and if it doesn’t, then you know you’re doing something wrong. […] It also opens up a shop window to showcase the best of what you do. There’s an opportunity for you to introduce people to the work that CNN does. 44

Hence, rather than a problem, this variation in fluctuations of online news video consumption can also be an opportunity for publishers to grow their audience and their reach, provided that they can predict at least a minimum amount of views in a given time period.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we identified the main ways that publishers directly or indirectly monetise their video news content. These include pre-roll advertising, post-roll advertising via Facebook’s suggested videos, branded/sponsored video content, and using news video as a marketing tool to increase reach and referrals back to destination websites. It remains early days for monetisation, with publishers and advertisers trying to find the right balance between getting messages seen without irritating audiences. Video has the potential to capture attention and therefore revenue in a more powerful way than text. Video advertising spend is growing year on year, but so is the supply of content, which may ultimately lower returns. The growth of off-site video offers new commercial opportunities, but there are also hazards with unpredictable spikes and potential changes of direction.

The future of online news video