Executive summary

In this report, we analyse how public service media organisations across six European countries are developing new projects and products to deliver digital news.

All the organisations we cover here face various external challenges, including discussions around the funding, remit, and role of public service media, pressure from private sector media competitors, the rise of platform companies, and continuetd changes in media use.

Our focus here is specifically on how they respond to these challenges and changes, and on the internal factors that those involved in developing new forms of digital public service news see as influencing the process of product development.

Based on examples from each organisation and 36 interviews with both senior editors and managers as well as people directly involved in each project or product, we identify four foundational factors that our interviewees suggest are necessary for the successful development of new forms of digital news in public service media organisations, and three additional factors that seem to facilitate it.

The four foundational factors are

- strong and public support from senior leadership;

- buy-in from the wider newsroom;

- the creation of cross-functional teams with the autonomy, skills, and resources to lead and deliver on projects; and

- an audience-centric approach.

These factors are foundational because they are not substitutable. Cross-functional teams may be necessary, but they are not sufficient to deliver change. The wider newsroom may want change, but if senior management does not lead, it will not happen.

Across our different case organisations and the countries covered, these seem necessary to develop and sustain new public service news projects and products.

The three facilitating factors include

- having a development department specifically for news;

- being able to bring in new talent; and

- working with external partners.

These factors in many cases seem to have facilitated development work, but they also represent specific solutions to challenges that can be handled in other ways.

The factors identified are in line with some findings from management studies and organisational sociology on change and innovation, while also being specific to public service media organisations.

External challenges and the wider change in our media environment are factors over which public service media organisations have little or no influence. The internal factors we have discussed here may be hard to influence, but ultimately it is within the power of public service media organisations themselves to change them.

To succeed in the future, public service media organisations have to be able to change – and continue to change – to develop their digital offerings, as the environment transforms. Political actors can, with public support, create an enabling environment for public service media. But it is up to the public service media organisations themselves to find new and effective ways of serving the public.

Introduction

As our media environment continues to become more digital, social, and mobile, all kinds of news organisations have to continually adapt and evolve. This applies to the public service media organisations we focus on here as much as it does to private sector legacy media and digital-born news media (Cornia et al. 2016; Nicholls et al. 2016).

In this report, we analyse how different public service media organisations from across Europe are developing their digital news offerings. On the basis of 36 interviews conducted between December 2016 and February 2017 with a mix of senior editors and managers as well as people working as part of the team behind specific new projects, we aim to better understand the development process itself and the factors that those involved see as key to facilitating the development of digital news products in public service media organisations. The countries we cover are Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and the United Kingdom. Together, they represent a range of different European media systems, levels of technological development, and public service media traditions.

The report is focused on the development process itself and the (mostly) internal factors that those involved see as key to facilitating the development of digital news in public service media. It builds on the report we published last year, Public Service News and Digital Media (Sehl et al. 2016), where we interviewed senior editors and managers across the same public service media organisations and countries about their views on the main challenges public service news face. We identified external and internal factors that are common to those organisations which have most successfully managed to reach a wide audience with their online news. In that previous report, we offer a more extensive analysis of how public service media organisations see their wider challenges in a changing media environment and how a range of external factors, including political ones, influence their ability to successfully deliver public service news online. 1

Here, we focus on how different people, including both senior editors and managers and people working on specific projects, see the development process itself. We examine how public service media organisations in these six European countries

- initiate new projects for digital news,

- create teams and develop new projects for digital news, and

- face challenges when they finally implement these projects.

We find four factors that our interviews suggest are foundational for developing new forms of digital public service news. These are (1) strong and public support from senior leadership; (2) buy-in from the wider newsroom; (3) the creation of cross-functional teams with the autonomy, skills, and resources to lead and deliver on projects; and (4) an audience-centric approach. All are necessary to develop and sustain new public service news projects and products. They are foundational because they are not substitutable. Cross-functional teams are necessary but not sufficient to deliver change. The wider newsroom may want change, but if senior management does not lead, it will not happen. We furthermore identify a series of other factors that many interviewees argue facilitate development, but do not seem foundational. These include (1) having a development department specifically for news, (2) being able to bring in new talent, and (3) working with external partners.

The organisations we cover are Yle (Finland), France Télévisions and Radio France (France), ARD and ZDF (Germany), RAI (Italy), Telewizja Polska (TVP) (Poland), and the BBC (United Kingdom). In each case, we asked the organisation to suggest a concrete project they thought of as a particularly important example of how they develop new digital products. These exemplify what is considered best practice in each organisation. The projects vary in scope from comparatively small ones, like the development of a video element within an existing app at the BBC, to larger undertakings like the merger of the news websites of France Télévisions and France Radio, two independent organisations in France. Generally, we looked for examples focused specifically on news, though that was not always possible (RaiPlay, for example, is a broader video-on-demand service). In each organisation, our aim (successful in most cases) was to interview senior editors and managers involved in making strategic decisions as well as people who had worked on the specific projects. Most interviews were conducted in person and on site, though one interview was done over the phone and one, with a representative from the Polish TVP, was done via email. For a complete list of interviewees, see p. 41. Our purpose was not to evaluate each project individually, but to better understand the process of development itself.

The report is structured as follows. First, we briefly discuss the challenges and opportunities our interviewees identified for public service news delivery in the digital age. Then we illustrate the different concrete projects that we analyse. After that, we focus on how the projects were initiated. We then analyse how teams were set up and explore the development phase. We go on to examine the implementation phase and challenges that occurred on the way. Finally, we identify the factors that our interviewees see as facilitating the development of digital news in public service media organisations, before we summarise the findings in the conclusion.

Challenges for Public Service News in an Increasingly Digital Media Environment

For decades public service media had a strong position in many European countries, often accounting for a large share of broadcasting and reaching most of the population with news via television and radio. Online, however, many public service media organisations have much more limited reach (Newman et al. 2016). In an increasingly digital, social, and mobile media environment, public service media compete for audiences with their ‘old’ private sector broadcast competitors, but also with other legacy media such as newspapers, with digital-born media, and in some respects with platform companies like search engines and social media. In a previous report on public service media we explored the challenges senior managers and editors at public service media organisations across Europe see for public service news delivery in this environment. Three challenges stood out as particularly central (Sehl et al. 2016):

- The first challenge was how to provide news for the whole public, including hard-to-reach younger audiences. Across the countries covered in this report, all public service media have a high reach for news offline, but their online reach varies. This is particularly clear when it comes to younger people. Calculations based on data from the 2016 Reuters Institute Digital News Report documents that there are significant differences in how many young people are reached by news from various public service media organisations. The BBC, for example, reaches 69% of 18–24 year olds in the United Kingdom with news across offline and online platforms on a weekly basis, whereas German ARD and ZDF reach respectively 35 and 27% in the same age group. 2 This is an issue ZDF is keenly aware of and heute+, the project we discuss below, is one of the ways in which they are working to meet this challenge.

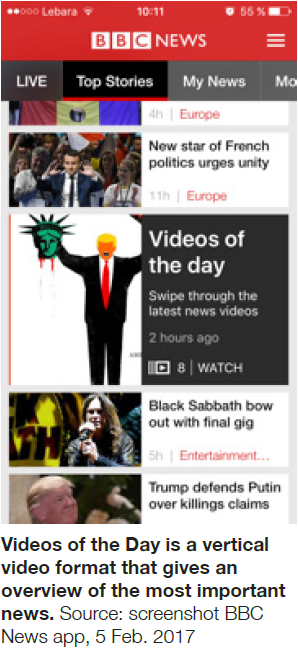

- The second challenge was to move from a strategy initially developed for desktop computers to one focusing on delivering digital news to mobile devices. Across the countries we cover here, between 32% (United Kingdom) and 20% (Poland) of online news users see smartphones as their main device for online news, and the number continues to grow. Among younger users, the percentages are far higher (Newman et al. 2016). The development of the BBC’s Videos of the Day that we discuss below is one example of how an organisation has focused on developing its mobile offerings.

- The third challenge was to deliver news effectively via third-party platforms like social media platforms, search engines, video hosting platforms, and messaging apps. Across the countries covered in this report, between 54% (Italy) and 27% (Germany) of online news users say that they consume news on Facebook. For younger respondents, the percentages are even higher (data from the 2016 Reuters Institute Digital News Report). Like other news organisations, public service media organisations are searching for the right balance between offsite discovery and distribution and the desire to ensure that users recognise and value the source of the content they consume, including the desire to bring users to individual public service media organisations’ destination sites and apps to avoid excessive reliance on third-party platforms. The development of the joint website franceinfo.fr by France Télévisions and Radio France is an example of public service media organisations investing in their own destinations even as they seek to explore other means of discovery and distribution.

The projects and products we focus on below are primarily oriented towards addressing one or more of these three challenges (reaching younger audiences, developing mobile offerings, navigating a more distributed media environment). All our interviewees of course recognise that these are accompanied by other challenges, including the broader underlying internal one of developing digital products and services in public service media organisations that are still deeply rooted in their broadcast legacy in terms of their organisation, workflow, and systems (Boczkowski 2004; Küng 2015) as well as a range of external challenges having to do with relations between public service media, political actors, and private sector competitors (Sehl et al. 2016).

Projects for Digital News – Case Studies from Six Countries

This chapter presents the projects we focus on in each public service media organisation. As mentioned earlier, the specific cases we explore were in most instances suggested by the organisations themselves. Following this, we cover a range of different projects – from comparatively small projects like the development of a video element within an existing app (BBC) to larger projects like the development of a video-on-demand platform (RAI) or the merger of the news websites of two independent organisations (France Télévisions and France Radio). For Italy, it was not possible to focus on news specifically and instead we explore RaiPlay, a video-on-demand platform. While we did not set out to study video specifically, almost all projects focus at least in part on video, reflecting a recent upsurge of interest in how to develop and deliver online video news (Kalogeropoulos et al. 2016).

Videos of the Day (BBC, United Kingdom)

Videos of the Day is a vertical video format the BBC introduced within its news app in November 2016. Users can swipe through a curated list of up to ten videos to get a summary of the top news stories. The videos are produced according to the needs of smartphone users, can be viewed vertically, and have subtitles. James Montgomery, director of digital development, BBC News, describes the main aim of the project as ‘to adapt [the BBC’s] video journalism for the mobile era’. 3 While the vertical video format is part of the main news app, it still seeks ‘a slightly younger audience’, according to Nathalia Malinarich, mobile editor for news, BBC News. [Nathalie Malinarich, mobile editor for news, BBC News, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 8 Dec. 2016, in London.]

Videos of the Day is a vertical video format the BBC introduced within its news app in November 2016. Users can swipe through a curated list of up to ten videos to get a summary of the top news stories. The videos are produced according to the needs of smartphone users, can be viewed vertically, and have subtitles. James Montgomery, director of digital development, BBC News, describes the main aim of the project as ‘to adapt [the BBC’s] video journalism for the mobile era’. 3 While the vertical video format is part of the main news app, it still seeks ‘a slightly younger audience’, according to Nathalia Malinarich, mobile editor for news, BBC News. [Nathalie Malinarich, mobile editor for news, BBC News, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 8 Dec. 2016, in London.]

More than 60% of BBC News’ digital traffic now comes via mobile devices. Also, a new video team has been installed working 24/7 in the main newsroom in London. [http://www.bbc.co.uk/mediacentre/latestnews/2016/swipe-for-latest-bbc-news]

The new vertical video format is part of the Newstream project that the BBC announced in September 2016 to bring video journalism to mobile. At the same time, the vertical videos are also published on the web, and on social media with smaller changes in design.

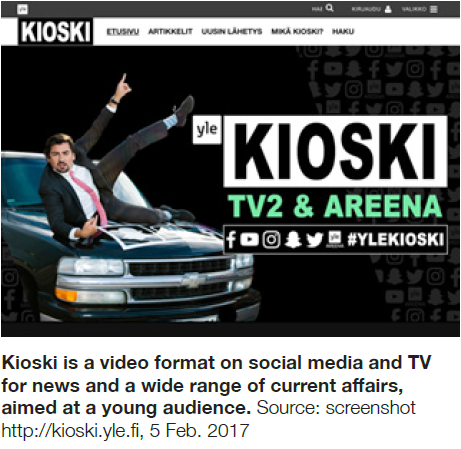

Kioski (Yle, Finland)

Kioski was launched in January 2015. Since then, the concept has changed a couple of times. Today, it is ‘a social video service for news and current affairs content’, says Antti Hirvonen, executive producer, Kioski, Yle. The aim behind Kioski is twofold, Hirvonen explains: ‘We have to try to catch those younger audiences we don’t otherwise catch, and at the same time, within Yle it is our job to have insight into reinventing news, how to put news into a whole new format on social media platforms.’ 4 To fulfil these tasks, a team of colleagues from different backgrounds – trained journalists as well as video editors and a blogger, for example – work across various digital platforms, not only Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter, but also Snapchat, Instagram, and WhatsApp. The analysis of metrics plays an important role says Nora Kajantie, producer of Kioski, Yle, enabling a better understanding of what kind of content the users are consuming, and how. 5 Kioski had almost 70,000 Facebook ‘likes’ in February 2017. In comparison, the main Yle News account (in Finnish) had just over 150,000 ‘likes’.

Kioski was launched in January 2015. Since then, the concept has changed a couple of times. Today, it is ‘a social video service for news and current affairs content’, says Antti Hirvonen, executive producer, Kioski, Yle. The aim behind Kioski is twofold, Hirvonen explains: ‘We have to try to catch those younger audiences we don’t otherwise catch, and at the same time, within Yle it is our job to have insight into reinventing news, how to put news into a whole new format on social media platforms.’ 4 To fulfil these tasks, a team of colleagues from different backgrounds – trained journalists as well as video editors and a blogger, for example – work across various digital platforms, not only Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter, but also Snapchat, Instagram, and WhatsApp. The analysis of metrics plays an important role says Nora Kajantie, producer of Kioski, Yle, enabling a better understanding of what kind of content the users are consuming, and how. 5 Kioski had almost 70,000 Facebook ‘likes’ in February 2017. In comparison, the main Yle News account (in Finnish) had just over 150,000 ‘likes’.

In addition to the distribution of content on the digital channels, there is also a TV show every Thursday evening. The show is also viewable on YouTube and Yle’s own platform Yle Areena. This has been reduced from five shows per week at the beginning of the format to only one per week today. At first the show was live, but now it is prerecorded. Although some voices within Yle doubt that TV is the appropriate channel to reach the targeted young audiences, the resources for the whole of Kioski, including social media, still come from the television budget within the organisation.

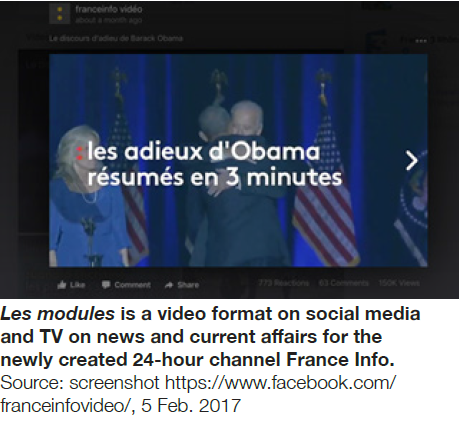

Les modules (France Télévisions) and franceinfo.fr (France Télévisions and Radio France, France)

In August/September 2016, France Télévisions and Radio France jointly launched the news offering France Info, consisting of a new 24-hour TV channel, a website, a news app, and social media distribution. An important element of the 24-hour TV channel is a format called les modules. It is a video format, working with special design and graphic elements, which are inspired by AJ+. The videos can be watched with or without sound. They are distributed both on TV and on digital platforms (website, app, social media). The aim of les modules, as of the whole 24-hour channel, is ‘to attract a young audience and thus to bring this audience back to public service news’, explains Julien Pain, senior editor, head of les modules, France Info, France Télévisions. 6 France Info had about 1.38 million Facebook likes in February 2017.

In August/September 2016, France Télévisions and Radio France jointly launched the news offering France Info, consisting of a new 24-hour TV channel, a website, a news app, and social media distribution. An important element of the 24-hour TV channel is a format called les modules. It is a video format, working with special design and graphic elements, which are inspired by AJ+. The videos can be watched with or without sound. They are distributed both on TV and on digital platforms (website, app, social media). The aim of les modules, as of the whole 24-hour channel, is ‘to attract a young audience and thus to bring this audience back to public service news’, explains Julien Pain, senior editor, head of les modules, France Info, France Télévisions. 6 France Info had about 1.38 million Facebook likes in February 2017.

The website franceinfo.fr is also a joint project of both French public service media organisations. In the past they each operated their own news website, but franceinfo.fr is now their joint product. However, the joint website was not built up from scratch, but took over the website architecture, the content management system, and the staff of the previous France Télévisions news website.

Tagesschau 2.0 (ARD, Germany)

The Tagesschau 2.0 app was launched in December 2016 and replaces an earlier app dating from 2010. The app is characterised by screen-filling videos in vertical format on the start page, although a horizontal view in 16:9 landscape format is still possible. There are 10–15 videos aiming to give an overview of the news of the day. They have subtitles and can also be watched without sound. For anyone who wants to know more, clicking on the video will lead to articles with deeper information, analysis, or comments. ‘We have tried to bring our main unique selling point to the app. That’s videos, which we also see as a consumption habit of the future’, says Christiane Krogmann, editor in chief of tagesschau.de, ARD. 7

The Tagesschau 2.0 app was launched in December 2016 and replaces an earlier app dating from 2010. The app is characterised by screen-filling videos in vertical format on the start page, although a horizontal view in 16:9 landscape format is still possible. There are 10–15 videos aiming to give an overview of the news of the day. They have subtitles and can also be watched without sound. For anyone who wants to know more, clicking on the video will lead to articles with deeper information, analysis, or comments. ‘We have tried to bring our main unique selling point to the app. That’s videos, which we also see as a consumption habit of the future’, says Christiane Krogmann, editor in chief of tagesschau.de, ARD. 7

Unlike the previous app, the Tagesschau 2.0 app features not only news from Tagesschau, but also regional news from the nine regional organisations of the ARD as well as sports news. Users can see the news in a chronological or a personalised order. Also new is a search function that is designed like a messaging service such as WhatsApp. Within the chat the user can search for certain topics and then see all texts and videos on this topic displayed. Finally, the app includes the ARD news bulletins Tagesschau, Tagesthemen, Nachtmagazin, and Tagesschau24 live as well as on demand.

In September 2016, ARD lost a court case against eight newspaper publishers relating to the previous app. On a reference day in 2011 the app was seen by the court as being too similar to press products. However, the legal process is still ongoing as ARD has appealed the court’s decision. Despite the video focus of the new app, the German newspaper publishers’ federation (BDZV) has already made it clear that they still see it as being too similar to their own products. 8

heute+ (ZDF, Germany)

heute+ anchor Eva-Maria Lemke during a social media live interview (left) and in the studio during the show (right) Source: Author’s own pictures

heute+ anchor Eva-Maria Lemke during a social media live interview (left) and in the studio during the show (right) Source: Author’s own pictures

heute+ is a crossmedia and dialogue-oriented news format distributed since May 2015 on various digital channels, most importantly social media, as well as on linear TV from Monday to Friday. It is aimed at younger target audiences. The first distribution at 11 pm is always on social media (Facebook and Periscope), then as on the news app and the video-on-demand site Mediathek. heute+ is also broadcast later on linear TV.

The concept of heute+ is to interact with users and integrate them into the reporting. Therefore, the two anchors of the format discuss selected topics with users during the day, asking for their opinion or input. These user comments are sometimes taken up later in the news format. Eva-Maria Lemke, one of the two anchors of heute+, ZDF, describes her role as being ‘more as a person who seems approachable to the user rather than someone who is just distributing news’. 9

‘Analysis and conversation’ is what Clas Dammann, heute+ team leader, ZDF, describes as the core of the format, ‘pure news is available everywhere’. 10 He further explains that 60% of the Facebook users are between 18 and 34 years old. They are therefore much younger than the average ZDF TV audience, which is over 60 years old. In February 2017, they had over 137,000 ‘likes’ for their Facebook page. However, reliable figures of how many users actually view the stream online are not yet available, as mobile use was not counted at the time of the interviews.

heute+ has replaced the traditional TV news bulletin heute nacht. The TV reach, after falling at the beginning, now exceeds the previous level, says Elmar Theveßen, deputy editor in chief, ZDF. 11

RaiPlay (RAI, Italy)

RaiPlay, launched in September 2016, is a video-on-demand platform for RAI content. It is accessible on a dedicated website https://www.raiplay.it/), via the mobile app, and on smart TV. Offline consumption is also possible as selected content can be downloaded. The focus is on entertainment. RaiPlay allows the user to watch, for example, TV shows, movies, series, sports, and also material from RAI’s historical archives. It streams 14 RAI TV channels and offers catch-up TV for the previous seven days. The platform especially targets young users who no longer consume traditional RAI broadcasts.

RaiPlay, launched in September 2016, is a video-on-demand platform for RAI content. It is accessible on a dedicated website https://www.raiplay.it/), via the mobile app, and on smart TV. Offline consumption is also possible as selected content can be downloaded. The focus is on entertainment. RaiPlay allows the user to watch, for example, TV shows, movies, series, sports, and also material from RAI’s historical archives. It streams 14 RAI TV channels and offers catch-up TV for the previous seven days. The platform especially targets young users who no longer consume traditional RAI broadcasts.

RaiPlay replaces a similar platform, RaiTV. Compared to this previous platform, RaiPlay has a more fully featured user interface and also offers editorial content recommendations. In addition, users can also register and personalise their content. To begin with these features were limited, but recommendations for videos based on previous user behaviour are planned. Although at present RaiPlay only offers content that has already been broadcast, Marco Nuzzo, deputy director, digital division, RAI, states that future plans also include original online content. 12

Compared to the previous platform, RaiPlay significantly increased usage shortly after its introduction. From 1 October to 30 November 2016, RaiPlay generated 75.5 million online video views from 15 million different devices. The number of online video views increased by 91% and the unique browsers by 65% from November 2015 to November 2016. 13

tvp.info (TVP, Poland)

tvp.info is the new news website of Telewizja Polska (TVP). It was originally launched in 2009, but went through a major redesign in 2014. ‘The need to rebuild the tvp.info website came from the rapid changes in how digital media is consumed. We knew that with an outdated website we couldn’t compete and we would lose the market share we had’, says Anna Malinowska-Szałańska, producer, Telewizyjna Agencja Informacyjna, TVP. 14 The relaunch focused mainly on two aspects: a responsive web design and interactive features, especially links to social media platforms.

tvp.info is the new news website of Telewizja Polska (TVP). It was originally launched in 2009, but went through a major redesign in 2014. ‘The need to rebuild the tvp.info website came from the rapid changes in how digital media is consumed. We knew that with an outdated website we couldn’t compete and we would lose the market share we had’, says Anna Malinowska-Szałańska, producer, Telewizyjna Agencja Informacyjna, TVP. 14 The relaunch focused mainly on two aspects: a responsive web design and interactive features, especially links to social media platforms.

Now that the different projects and products have been introduced, Chapters 3 to 5 will explore the whole development process – from the start through the core development phase up to implementation.

Initiating a New Project: The Decision for a Project

Identifying and prioritising the right projects for digital news is a continuous task for news organisations seeking to keep up with the changing media environment. In the specific cases we have analysed, almost all projects were initiated by the directors of news and current affairs or even the CEOs/Director-Generals of the whole organisation. This may have been due to their central importance for the organisation. In general, there are also bottom-up-structures or informal ways to identify and pitch for new projects to work on. Across a number of public service media in our sample, the need to reach young target audiences was a catalyst for the start of new news projects. This chapter addresses how the projects in the different public service media organisations started.

At the BBC, the Future of the News report 15 was a starting point for a project called Newstream, of which vertical videos are one part. The Future of the News was commissioned by James Harding, then the new incoming director of BBC News and current affairs, and was put together with the input of people working inside and outside the organisation, including journalists, academics, media leaders, and technologists.

In general, Nathalie Malinarich, BBC, describes the core challenge as not necessarily being to develop new ideas, but to get buy-in for them from the organisation: ‘It’s not necessarily easy to get buy-in from the organisation, and I think it’s partly to do with the fact that different parts of the organisation are responsible for their own little bits so you can’t always do it within your own team.’ She concludes that this was relatively easy for the vertical video project, helped by the fact that the project was initiated by the director of news and current affairs. 16 The BBC also has a variety of people with strategy roles as well as its own BBC News Labs, working at the edge of news, research and development, and news, product and systems. The BBC tries to foster ideas for new pilots not only top-down, but also within their teams. For example, so-called ‘Digital Away Days’ are organised, explains Ramaa Sharma, editor, digital pilots and skills, BBC News, to give journalists an overview of the current challenges and changes. 17

At Finnish Yle it was a television channel, TV2, that actually provided the impulse to work on a new format that later became Kioski: ‘They wanted the news and current affairs section to create a news and current affairs show for channel TV2 that would reach a younger audience’, says Antti Hirvonen, Yle. 18 In general, Yle has a dedicated development team for news that regularly identifies and proposes possible projects to the news and current affairs management. Aki Kekäläinen, head of web and mobile development efforts, news and current affairs, Yle, explains:

The most important thing is to understand the goals and then we analyse what options we have to reach those goals. After that, we select the projects. … I think the most important thing is to understand what we have to achieve so we are important, and to stay important for Finns in the future as well. 19

Ideas for new projects, including first concepts, are regularly developed in so-called internal hackathons, notes Atte Jääskeläinen, director of news and current affairs, Yle. 20 Similar events, also with outside actors, are regularly conducted at the BBC News Labs, according to Robert McKenzie, an editor there. 21

In France, at France Télévisions and Radio France, both the merger of the websites of these organisations and the creation of les modules were decisions made by the CEOs of the organisations following the decisions to introduce the 24-hour news channel and to have one joint public service news website. This top management support was highlighted as an enabling factor by the interviewees in France. France Télévisions has two departments working on new ideas, the Media Lab and Les Nouvelles Écritures.

In Germany, in both public service media organisations ARD and ZDF, the projects we describe in this report were initiated respectively by Dr Kai Gniffke, first editor in chief of ARD Aktuell, and Elmar Theveßen, deputy editor in chief of ZDF. While at ARD they saw an urgent need to adapt their six-year-old news app to the new technological standards, at ZDF, similar to Yle, working groups were created to think about new ideas for reaching younger audiences with news. In general, ARD also has a development team especially for news, that observes the market, regularly visits industry events, and keeps in touch with other media companies. The development team meets regularly with the news and current affairs management to propose topics that could be relevant for news at ARD. ‘Look, listen, stay alive’, is the simple motto that Andreas Lützkendorf, head of strategy and innovation, ARD Aktuell, uses to describes the more complex task of identifying and prioritising new projects. 22

Dr Kai Gniffke mentions that whether to introduce a new project by a top-down or bottom-up approach requires careful consideration. At the moment, ARD is planning a new newsroom in which TV and online staff can sit together. In this case Gniffke has initiated the process, but ideas are developed bottom-up: ‘For a project that aims to create a new newsroom in which people then have to work, I think it would be difficult not to have broad participation from the employees.’ 23 At ZDF there is no formal development team specifically for news, only one for new media in general. Apart from that, the creative spirit and the engagement of employees often initiate projects, Robert Amlung, head of digital strategy, ZDF, explains:

The development structures in this company work like a network. People have ideas, ask their boss if they can do it. If they are lucky, the boss agrees and gives them the freedom and maybe an extra shift. They are using their own free time. That’s how it usually starts. 24

In Italy and Poland, the decisions to renovate the video-on-demand offer and the website respectively were also made by the (top) management in order to bring existing products into line with up-to-date technological standards. In Italy, the general director of RAI established the digital division at the end of 2015 which has now developed RaiPlay. Polish TVP has a development division, but for the organisation as a whole and not specifically for news. In Poland the re-design of the news website was initiated by the director of Telewizyjna Agencja Informacyjna.

This chapter has shown that all these projects were initiated by the directors of news and current affairs or even the CEOs of the whole organisation. Their support was seen as an essential factor by interviewees. However, this top-down approach is not the only option. Other projects have started from different departments within the organisations. In certain cases, the management consciously initiates a project bottom-up to allow for broad participation, input, and eventual acceptance. Ideas for new projects also come from development departments, but not every public service media organisation has such a department. Organisations that have a development department described it as useful for observing the market and working on new ideas and projects.

The Actual Work: The Project Team and Development Phase

Once a project has been identified and prioritised within an organisation, a project team has to be formed and then begin the actual development process. This chapter illustrates how such project teams were formed for specific projects in the six public service media in our sample. It explores the nature of the work structures for the projects, and similarities or differences between these and other projects for digital news within the organisations. The chapter also focuses on how the work was done in these teams in the actual development phase.

At the BBC, the project on vertical video was realised with a comparatively small team of three core team members leading the editorial as well as the product side of the development, as well as colleagues from user experience and development. This limited team size was seen as an advantage by the members involved. For example, James Montgomery, BBC, points out: ‘In my experience, … you need a fairly small team. And at the same time, … we did a lot of communication so that everyone knew what was going on, everyone had a chance to input.’ 25 That the project was initiated by the BBC director of news and current affairs was also helpful in getting collaboration from other parts of the organisation, according to Nathalie Malinarich, BBC. 26

In addition to the internal personnel, the project team worked with an external design agency that was recruited through a public tender, as well as with another company. External collaborations can be helpful in developing concepts, says James Montgomery: ‘I think the collaboration with an external agency in general can give a creative stimulus during thinking. … It helped us evolve our design thinking very quickly.’ 27 He argues that the configuration of the team was fruitful for the project: ‘I think it was a good balance of editorial and technical people, and a good balance of internal and external perspective.’ 28

During the development process, the core project team was able to focus solely on this project. ‘We slightly isolated ourselves from the rest of what was going on’, explains Nathalie Malinarich. 29 The importance of this aspect is, in more general terms, also highlighted by Fiona Campbell, controller of BBC News mobile and online:

I think that, especially in relation to the public sector, if they’re working on an existing core product, you’ve got an existing hierarchy, existing levels of expectations, and existing workload and an existing daily volume of work they’ve got to do. Then if you add on a bit of something else, the bit of something else will always come secondary, … because they’ll be afraid of not delivering the right volume. The show will always have to go on air. The editor will still have the expectations. Therefore, there’s no room to push it or to risk it. 30

The actual development phase took about a year and is described by James Montgomery as a ‘slim[ming] down’ 31 of ideas: ‘Some of which were either discarded because we felt we didn’t need them, or they were too ambitious to do, or would take too long.’ 32 When working on a concept, the interviewees looked at various other players in the market – public service as well as private media like AJ+, the Voice app, Yahoo News Digest, and others – in order to learn from them. After a prototype had been built in cooperation with the external agency, the team focused on audience testing and tweaking of the product.

The BBC organised focus groups and surveys on video more generally in London and abroad as well as a specific testing of a prototype before the actual app element was built. ‘You know, with early prototypes, and a lot of usability testing, to see if they understood the navigation and how they felt about the content and stuff’, says James Montgomery. 33 Later on, a beta version was launched to 100,000 Android users in the United Kingdom to test how they would actually use the app and to identify possible challenges for the main release.

At the Finnish broadcaster Yle, the project team was not only excused from the daily news operations during the development process, but also removed from the newsroom. ‘We moved them into a different building altogether. We tried to separate them. … It was a very deliberate thing to do. At some point, I was worried that they were drifting too far apart’, says Mika Rahkonen, head of development/media lab, news and current affairs, Yle. 34 This distance from the main newsroom and the freedom to concentrate on the development process was meant to encourage thinking out of the box and provide enough time to do so. Aki Kekäläinen, Yle, explains the decision to let the core project team just concentrate on the development: ‘If you want to be the best, you have to focus on being best in one area.’ 35 He also mentions that this focus helped the team to have clear responsibilities for project developments, with no discussions about how to prioritise different duties.

At Yle, as at the BBC, the core project team was small with only three team members. As their task was to develop an editorial concept, the core team consisted only of journalists. However, they were joined by colleagues from other areas of the organisation for occasional support, e.g. from the development department to help them get started. For a later revision of the TV concept, a production company was involved. Nora Kajantie, Yle, thinks that the outside perspective is very important and could have been more pronounced in the first concept: ‘Looking back, maybe we should have had more views from out of house about the first concept and built it on what we could do – not should do’. 36

For Kioski, several interviewees report that the development phase was comparatively long, between four and six months. Atte Jääskeläinen, Yle, for example says, ‘We are impatient, so we sometimes jump the gun a little bit and take the plunge before planning too much. I think in Kioski we did much more than usual of the conceptual thinking at the beginning.’ 37

Within the defined goal, to make efforts to reach younger target groups, the core project team had freedom to think of a concept. At the same time, the development department protected them against unhelpful criticism: ‘Whenever you get the new generation, you get new language and whenever you get new language you get people saying it’s not news because you’re not doing it the way I did’, says Mika Rahkonen. 38

In the first concept, Kioski started with five TV shows a week, a website, and social media as distribution channels. Today, just a weekly TV show and social media remain as distribution channels and the concept has changed from more text-based to video-based. The interviewees consider that the real work on the concept in this case only started after the project had been launched (this will be described in the following chapter on implementation).

At Yle, audience research is an important part of every product development, explains Mika Rahkonen. 39 This public service media organisation has not only developed a handbook with a clear segmentation of different online users and their desires and needs, but also uses audience testing before the launch of every new product. ‘We had people coming over, we showed them clips on TV. We had them read web articles. We asked them which they were interested in, what topics and what approach would work, what wouldn’t work.’ 40

At Yle, audience research is an important part of every product development, explains Mika Rahkonen. 39 This public service media organisation has not only developed a handbook with a clear segmentation of different online users and their desires and needs, but also uses audience testing before the launch of every new product. ‘We had people coming over, we showed them clips on TV. We had them read web articles. We asked them which they were interested in, what topics and what approach would work, what wouldn’t work.’ 40

At France Télévisions and Radio France, project teams for les modules as well as the joint news website of both public service media organisations in both cases consisted of cross-sectional teams with editorial, management, and technical competencies. A peculiarity of les modules is that the format has to work not only for internal partners of France Télévisions, but also for other external French public service organisations such as the French National Audiovisual Institute (INA) or the Franco-German channel ARTE.

The new developments at France Télévisions as well as Radio France within the context of the new 24-hour news channel each took roughly a year. Jean Chrétien, deputy executive manager of France Info, France Télévisions, mentions one phase of the development process that stands out. This is the phase of negotiation with the unions after the general concept for the new 24-hour news channel had been developed. 41 Dialogue with the unions was not explicitly mentioned in any of the other countries in our sample, highlighting the strong role unions have in the public sector in France whenever job profiles are changed or new ones created. The process of merging the websites of France Télévisions and France Radio, as well as the wider process of introducing the new 24-hour news channel, even led to strikes in both companies. As Antoine Bayet, director of digital news at France Info, the all-news radio channel of Radio France, describes: ‘Within France Télévisions the problem was planning the demise of the Francetv Info brand. We had to negotiate with the editorial team. This was difficult. There were some strikes on their part. So it was hard, very hard. Very hard times.’ 42

When brainstorming for ideas and working on a concept, both France Télévisions and Radio France mention not only the importance of inspiration from other outlets, but also the need to work on their own ideas instead of copying. ‘The first project team … looked at Vox and AJ+. … Now we’re far enough away from AJ+ and Vox. We are concentrating on our own developments, our own formats’, concludes Julien Pain, France Télévisions. 43 His colleague Pascale Manzagol, senior editor, France Info, France Télévisions, points out how most formats in the media industry are just copies of one another:

The Guardian was a point of reference in terms of computer graphics, flat design, and so on. AJ+ was a reference for the subtitles issue. There were other sites, but you soon realise that everyone is copying. There is an enormous amount of ideas that are recycled within the industry. It’s impossible to say who came up with an idea first. 44

In contrast to BBC and Yle, France Télévisions did not conduct any audience research before the new project was launched. Due to a lack of time, qualitative audience research was only conducted two months after the launch of the channel, as Jean Chrétien explains. 45 In addition, audience data was monitored for TV and online. Both resulted in slight changes to les modules.

In Germany at ARD, the team for the new news app consisted of ten people. Half of them were involved almost full time throughout the project, while others only occasionally supported the development phase or were more involved at a strategic level, as Christian Radler, editor, strategy and innovation, ARD Aktuell, explains. 46 Besides him and the head of strategy and innovation, two web designers, a graphic designer, journalists from tagesschau.de, as well as the editor and deputy editor in chief of tagesschau.de and the first editor in chief of ARD Aktuell, were involved in the process. In general, due to work pressures and limited resources, it is difficult at ARD Aktuell to allow journalists to concentrate only on a development project. They usually also have to continue with their normal work, as was noted by Christiane Krogmann, ARD. 47

Two external firms complemented this internal team with programming know-how and resources/capabilities. One was involved in the concept planning and built the new app, while the other was responsible for a connection to the existing website content management system.

The project team for the news app met every week to discuss and plan the next steps and to monitor the progress of the project. Rike Woelk, deputy editor in chief of tagesschau.de, ARD, remembers: ‘We divided the work up into packages that each had a deadline. Of course it would have been possible to work half a year longer on each aspect. … But you have to learn to stop at a certain point, as resources are also limited.’ 48

The development on the new Tagesschau 2.0 app took about 15 months in total. The work on the concept phase was kicked off by two workshops. Dr Kai Gniffke, ARD, recalls that ‘What do we expect from a new app? And what do we think the user expects from a new app?’ were the questions underlying the first workshop. 49 Following these questions two concepts were developed. During this concept phase, the team members looked for inspiration at a wide array of other outlets, public and private media, says Rike Woelk. 50 The product development department also visited or had been in direct contact with other public service media like the BBC and Yle to learn from their experiences. However, Christiane Krogmann felt that the most important thing was to be aware of their own needs and strengths. 51

User testing was carried out during the building of the app and also shortly before the launch. The first test was a traditional survey with a representative group of users, conducted in cooperation with the external agency in charge of building the new app. The subsequent test was a launch of a beta version to 2,000 users of the previous app, to flag up possible problems before the actual launch date. In addition, editorial analytics have recently been gaining more importance at ARD Aktuell, although they had been somewhat neglected in the past, as Dr Kai Gniffke confesses. 52 In general, Andreas Lützkendorf, ARD, describes audience testing as also being a way to justify spending public money: ‘Nothing can be guaranteed, but at least we get a feeling that we are not heading in the wrong direction.’ 53

At the other German public service broadcaster, ZDF, two working groups were created to think about concepts for news that might appeal to a younger target group. The group members came from different areas of ZDF like the children’s news magazine logo!, the political satire heute show, or audience research. Journalists were involved in these working groups, but also other professionals such as graphic designers. In general, Robert Amlung, ZDF, sees such diversity as helpful in creating a ‘creative tension’ within the project team. 54 Additionally, ZDF cooperated with two external firms. One produced the first pilot, while the other worked on the current graphic design. The cooperation was necessary because ZDF’s own departments such as graphic design were busy with day-to-day operations. Clas Dammann of ZDF also found this ‘external pingpong’ to be fruitful for the project. 55

As at ARD, only a few people at ZDF were involved throughout the project, while others supported it occasionally. Leave of absence was only granted to journalists in the team to produce the first pilot of the project. Otherwise they had to do the project development work in addition to their normal jobs, notes Clas Dammann. 56 He also remembers that the project group was very autonomous in its work within the clearly defined project goals and tight coordination with the deputy editor in chief of ZDF. ‘This meant, of course, an enormous push for the working groups and its members … to get away from a routine approach and to show what is possible.’ 57

The intensive work phase took about nine months, but discussions and working groups started about three years before the actual launch. During the concept phase, the working groups looked at a wide range of ideas, e.g. VICE, vox.com, and BuzzFeed. However, Clas Dammann underlines that this only provided inspiration to start to develop their own original concept, not just simple copying:

It was never our aim to imitate other online products. That would have been the biggest mistake. Others have done that and imitated the aesthetics of YouTube. … If we did the same, it would be doomed to failure. But we can think how we can use this more personal and authentic approach of reporting in our own way, how we approach topics, see what’s possible. 58

The concepts were then presented to the top management to allocate the necessary resources. When these became available, a design for one of the two concepts on TV and social media was developed with the external agency.

Along the way, two audience tests were done. The first of these led to what Clas Dammann calls ‘disastrous results’, but the second one was satisfactory. 59 Dammann explains that the material for the first test had not been sufficiently well produced, and it was important to understand why the audience test failed and not just immediately throw the whole concept into question. 60

At RAI in Italy, a digital division was introduced at the end of 2015 to develop products for digital. Like the project development that we describe in this report, RaiPlay, the RAI digital division is not focused specifically on news. The division does work on news projects, but in close collaboration with the journalistic division which keeps responsibility for the editorial aspects. Unlike the other projects discussed so far, RaiPlay was almost completely developed and implemented without any cooperation from outside the organisation. The whole platform was built within RAI. This speeded up the development process enormously, argues Gianpaolo Tagliavia, chief digital officer and head of the digital division, RAI: ‘Because of the specificities of the broadcasting world that RAI finds itself in, if you have to buy an external platform, it takes five years before you can launch it.’ 61 While only about ten people worked on the development of the project, coming from editorial, technical, or social media backgrounds, the number involved in producing the platform was much higher. The new digital division is seen by Marco Nuzzo, deputy director, digital division, RAI, as a major factor in a development that was, in his point of view, more oriented towards the user than internal organisational requirements: ‘In the past we, at RAI, were quite inward-looking, but RaiPlay was born with a more extended vision, a vision that is directed more towards the outside world than towards our internal requirements.’ 62 Therefore, team members focusing on user experience were included from the very beginning of the project.

RaiPlay was developed and implemented in only nine months. It built on a previous project: ‘An embryo of the project was already present within the company’, as Gianpaolo Tagliavia, RAI, explains it, ‘but RAI had made the mistake of somehow marginalising it.’ 63 The new RaiPlay project put the user first, rather the internal organisation of the work around it: ‘We started by defining what we wanted to offer to the customer.’ 64 The BBC as ‘the champion among the PSBs’ 65 and also Netflix as a commercial player, ‘as it has a different logic, that is a pay logic’ 66 were role models in this process. When the concept was clear, the editorial, graphic, and technological requirements were sorted out. Similarly to France Télévisions, the interviewees at RAI argue that the time of the development process was too short for audience testing to be done before the launch. They only did computer-assisted telephone interviews (CATI) and focus groups after the product had already been launched. ‘Thank God we guessed right’, concludes Tagliavia. 67 Instead of having a beta testing phase with the audience, like the BBC or ARD, RAI only did internal beta testing with project members.

At Polish TVP, the project team that was set up specifically for the redesign of the website consisted of four members: a manager, an IT journalist, and two other journalists. In addition, an external agency was commissioned to help with the interactive design, describes Anna Malinowska-Szałańska, TVP. 68 The whole development process took about five months. The relaunch of the news website aimed at what the members of the project team perceived as audience expectations, she explains. 69 A concept for the relaunch was developed with a model of a typical TVP user in mind, and then further elaborated and produced in cooperation with an external agency. Beta testing with selected users was done, as at the BBC or ARD, to test for any bugs or get feedback on improvements before the actual launch of the new product.

In sum, the chapter has shown that all public service media organisations in our sample set up project teams for their specific developments that consisted of team members with various backgrounds. Depending on the specific needs of each project, the team members had not only editorial, but also technical or management skills. Apart from that, the chapter has shown that there are three main differences in the structures within which the projects are set up:

- if the organisation has its own development department to help guide the process;

- if the organisation can afford to have project team members who concentrate solely on the current project development or if they have to do the development work alongside their normal job responsibilities; and

- whether partnerships with external firms are entered into.

The first two points usually depend on resources, whereas views among our interviewees differ on the last point. Many interviewees see working with external partners as an invaluable way of bringing additional external expertise to the table and shaking up thinking. In contrast, interviewees at the Italian RAI argued that in-house development was more time efficient since RAI’s internal requirements are complex and it takes time for external firms to get up to speed.

The chapter has further shown that the development phase is structured from brainstorming to a concept, from a concept to a prototype, and then in many cases audience testing and tweaking of the product. During the brainstorming phase and the work on developing the concept, all the public service media interviewed mentioned that they looked for inspiration at other public services as well as private players. However, in many cases they emphasised that they then built on these ideas. Link to external firms brought additional ideas, as a couple of interviewees mention. Audience testing was generally seen as important by all public service media organisations in the sample, to guarantee audience acceptance of the later product. However, in only half of the cases was this done during the development process or before launch. In two other cases it was done after launch, and in one case there was only a test with a beta version. The example of Kioski at Yle shows that audience metrics provide another opportunity to continually monitor the acceptance of a new concept and to gradually adapt it.

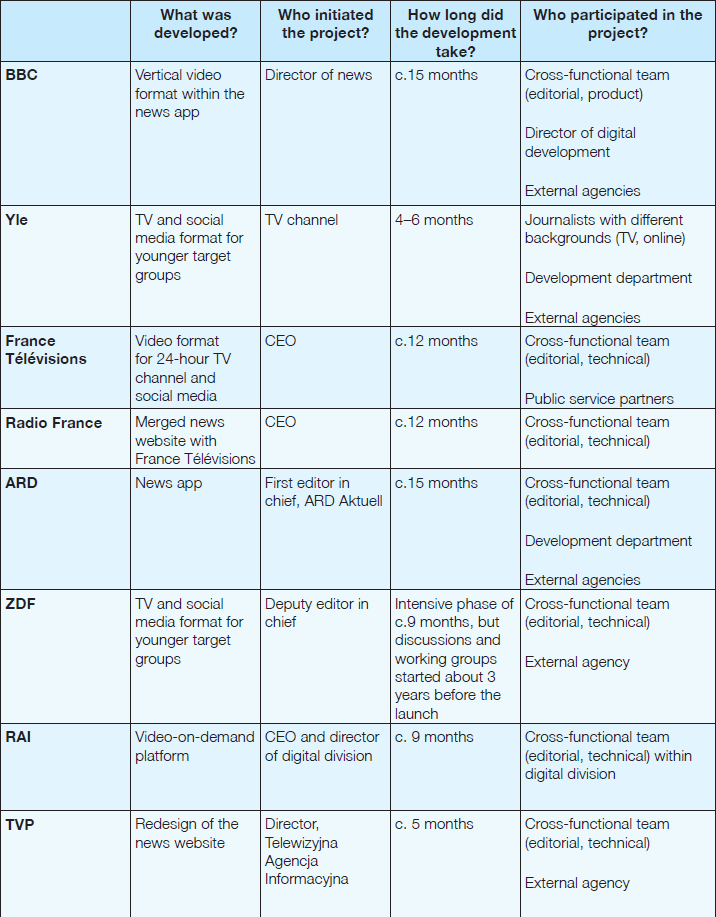

Central points of the project infrastructure and the development process are summarised in Table 1 following.

The Reality Check: The Implementation Phase and its Challenges

When the development phase is completed, the project or new product has to be implemented. Challenges may occur at this stage, as a quote from Christiane Krogmann, ARD, illustrates: ‘One can talk for a long time about an issue. When it comes to implementing it into daily work, then it always happens that new challenges come up that you have to deal with.’ 70 Her colleague Rike Woelk, ARD, notes: ‘it is important to follow this phase very closely, not only from the point of view of the people who were involved in a project, but also from the point of view of those who now have to deal with it in their daily work.’ 71 This chapter focuses on the implementation phase and its challenges.

At the BBC, the implementation phase was done by a video team of existing and new journalists. They worked not only on the new Videos of the Day format, but also on other video formats for BBC News. When this team started to work in the newsroom, the other journalists there had already known about the project for a long time. Nathalie Malinarich, BBC, explains: ‘When the team started work, it started in the newsroom and I think that was a good signal to the rest of the newsroom.’ 72 However, she admits that it also caused some friction to start with, as the team had already started to work in the newsroom before the official launch of the product and was still experimenting. ‘So maybe I should have done some of the other work outside the newsroom and then gone in with something a bit more established’, she concludes. 73

Apart from that, interviewees also mention small challenges on the technical side, mainly because most workflows and content management systems at public service media are still built for broadcasting. This led to delay at the end of the project that lasted about a year in total. Nathalie Malinarich explains how delays can easily lead to frustration among project members. She concludes that it is sometimes better to launch earlier to avoid this and to have the additional benefit of receiving user feedback sooner:

I would have launched earlier even if it was less perfect, I think, just because I think the delay opens you up to people asking questions that aren’t necessarily helpful, sometimes at the very last minute. When you’re ready to go, something small has to change – something that wouldn’t have been a problem if you’d done it three months earlier. I think there can also be an issue with staff morale … If you have a team working for many months on something that’s not public, it just becomes very difficult if it’s not changing. Things were changing in the sense that the quality was improving and they were learning a lot, but it was still that frustration that you don’t have that feedback from the audience, which I think when you work on digital platforms, you just kind of want to know. 74

At the Finish Yle, the challenges in the implementation phase were greater as the concept had to be adapted a couple of times. For the start of Kioski a team of journalists and anchors from within Yle and outside was set up, not all of whom were professional journalists (e.g. a blogger). The aim was to bring in fresh ideas and skills, as Antti Hirvonen, Yle, explains, but that also led to new challenges: ‘I’m happy that it worked out but of course when you have a lot of young people working it’s different than when I used to work there in the YLE News because you also need to have that support and you have to teach them some things.’ 75

Since the beginning of Kioski, the format has changed several times. Five shows a week was reduced to only one show a week when it became clear that linear TV is not the best medium to reach the targeted audiences. A website with text articles was abolished, and finally the concept changed from being text-oriented to having a clear focus on video on social media platforms. The interviewees were already talking about Facebook Live becoming more important for the format in the near future. As this process shows, Kioski started with an idea that was challenged by audience behaviour and as a consequence was adapted again and again after it was launched. Mika Rahkonen, Yle, explains:

We made a lot of experiments with the TV thing and started with the home page and little by little just started analysing what works and what doesn’t. Do we reach the difficult audiences with this? No, okay let’s give it up. How about this? Well, yeah, okay, let’s develop it. 76

Kioski lost some team members during this adaptation process, as not all employees were happy with a product, and thus a work environment, that was constantly changing. ‘During the first year, many people we had recruited left Kioski. I think our first half-year was really chaotic for us and some people just wanted to go’, remembers Antti Hirvonen. 77 Today, openness to constant changes is one important criterion when potential new team members are interviewed. 78

The interviewees are in agreement that they feel they are finally over the hump with their current concept, but will develop it further as the environment and audience media consumption continue to change. They see the overall value of Kioski as having three aspects: learning to reach a target group that is otherwise difficult to reach with public service news; experimenting and gaining experience with new ways of storytelling; and finally bringing back this knowledge to the rest of the organisation. Mika Rahkonen, Yle, even argues that a public service media organisation always needs such an experimental project exploring different channels, so that the organisation can continue to learn and adapt:

I don’t think Kioski is going to be forever. What should be permanent, I think, is that we should have an experimental project going on at all times that has something to do with broadcasting as such, because Kioski does radio, Kioski does TV, Kioski does web, Kioski does social media a lot. We have to have an experimental project that does all this, because otherwise it’s really hard to develop new stuff. 79

At France Télévisions, one half of the team for les modules consists of France Info’s journalists (some of whom are newly employed young journalists) and the other half are journalists from the national TV channels. These colleagues only come in to support the work on les modules for a week at a time and then are replaced by other colleagues. The idea behind this constant exchange of team members is to save resources, but also to spread creativity within the organisation, explains Julien Pain, France Télévisions. 80 However, it also leads to the situation that further developments are easier to conduct with the dedicated team:

We can say that this is all because of our agile team. With them, we can experiment and innovate the most. Because we see each other every day, we know each other very well. … Then there are people from the national editorial staff who come in. They have a lot of journalistic skills, but they are people who come just for a week, then go back to their desks and come back again six months later. … They come and they go, so it’s hard to think about new formats with them, because they’re only here for a week at a time. 81

In general, the reaction of colleagues within the organisation to the new product was quite positive, summarises Pascale Manzagol, France Télévisions, 82 even though before the launch they only knew about the project in general, not what it would look like. However, when it came to the question who wants to work on for the format, the answers varied: ‘How a reporter of France 2 Political Service will work for this channel is a little more complicated. There are those who will adhere to it, and others who will not.’ 83

Antoine Bayet, Radio France, remembers that at the launch of the joint website between France Télévisions and Radio France, details of the processes were still not fixed and it was more a case of learning by doing. For example, a communication channel between the two different public service media organisations and people involved in the joint website was spontaneously set up on WhatsApp on the first day: ‘To put it frankly, [the implementation phase] was really a work in progress. … Finally, and today I think this is our strength, we built a WhatsApp channel where all our chief editors can interact with the chief editors of the digital part of France Télévisions.’ 84

At German ARD, the videos, which are the new element in the news app, are produced by a team of video editors who had previously worked only on a short news format called ‘100 seconds’, located in the television newsroom. Now they produce the videos for both formats, ‘100 seconds’ and the app, in one process, and have moved to the online newsroom. The interviewees see this as a small first step in the direction of a more integrated future, with a new newsroom that is planned for 2018.

The challenge in the transition phase from development to implementation is to take the people who are not involved in the development process with you, to explain to them how you have arrived at a solution and what you now expect from them, explains Christiane Krogmann, ARD. ‘We keep our ears open for them and their concerns. During the whole process, we had meetings where they were encouraged to speak out about everything that worried them.’ 85

ARD launched a beta version of the app for 2,000 users for two weeks before the official launch to test the app and how it was perceived by the audience. Rike Woelk, ARD, describes that this procedure, which is common in software development, is still unusual for a public service media organisation as well as for their audience:

What is standard for software development, to go out with a beta version, to receive feedback and to develop the product further – that is still unfamiliar for Tagesschau as well as for our audience. … For decades the audience had been used to Tagesschau only releasing a product when it was already really perfect. 86

At German ZDF, a small team was set up for heute+ consisting of journalists who had worked for the news bulletin heute nacht that heute+ replaced and members from the working groups that developed the concept of heute+. However, as several interviewees explain, a bigger challenge was to motivate and teach correspondents in the different regional studios and abroad to produce news pieces in the new format needed for heute+. Elmar Theveßen, ZDF, related that they toured the regional studios before the implementation, in order to motivate and show the colleagues there how to produce news pieces in the new format. 87 Templates had been distributed before the launch to facilitate the production.

Clas Dammann, ZDF, says that in the early days, when heute+ was soft launched on social media while TV still broadcast the traditional heute nacht news bulletin, the team had to gain experience with the format and learn how to find the appropriate tone: ‘We had two or three slip-ups, because we sharpened things up too much, and this had unexpected knock-on effects.’ 90. Clas Dammann, team leader, heute+, ZDF, interviewed by Annika Sehl, 16 Dec. 2016, in Mainz.] Thomas Heinrich, head of news, ZDF, sees the experimentation at heute+ as giving a valuable impulse to the wider newsroom. 88

At RAI, RaiPlay was by far the biggest project for the digital division until its launch, and required most of the resources of the division. Marco Nuzzo, RAI, describes more than 50 technicians being involved on the product side, although staff numbers were reduced after the launch. 89 At the same time, a team of more than 40 editors started to work on the content side, as Maria Pia Ammirati, RAI, explains. 90 The project has a strategic role that is part of the transformation process of the whole organisation and an ongoing challenge:

This is an important project, a project that involves a substantial transformation for RAI. It is not a ‘here today and gone tomorrow’ project. Having said that, we also know that consumption patterns, as well as technologies, are changing rapidly. With this in mind, we have to stay up-to-date in order to monitor all the developments. Thus, while the product will surely be transformed, it is a long-term project. 91

At Polish TVP, time was a challenge when implementing the new website tvp.info and there were also a few technical problems: ‘We had a very tight schedule, so people had to work very hard. Another problem was migrating assets from the old infrastructure to the new one’, says Anna Malinowska-Szałańska, TVP. 92 A new team of journalists was set up to work for the website. During the development process, all journalists in the newsroom were encouraged to give their feedback on the project. The website is seen by the TVP representatives as a valuable new way of delivering news to the public.

In brief, the chapter has shown that there are internal as well as external challenges in the implementation phase. The public service media organisations in our sample have underlined the importance of communicating the project to the whole newsroom early enough, and giving them opportunities to provide feedback as well as motivating them to collaborate later. Buy-in from the newsroom and a general culture of willingness to adapt to digital is, in that sense, essential.

Technical challenges can also occur on the internal side. Externally, users and how they accept the new product are the central reference point. In several cases this has led to further smaller – or in the case of Yle, larger – adaptations. Some projects, like at the BBC, took longer than planned while others, for example at Yle, France Télévisions and France Radio, or RAI were completed in a shorter time span, partly due to time pressure. The example of Yle shows that fine-tuning, or even more substantial adaptations if necessary, is still possible when a product has already been released. Also, the BBC and ARD had beta versions of their app or app element released before the official launch. This marks a difference between digital media and traditional broadcasting. Many projects in public service media organisations are still run on what in software design is called a ‘waterfall model’, sequential and non-iterative processes of conception, initiation, development, and implementation very similar to those used in manufacturing and construction industries, where after-the-fact changes are difficult and expensive. ‘Agile’ principles of collaborative cross-functional teamwork anchored in product managers and aiming at facilitating adaptive planning, evolutionary development, early delivery and continued improvement through iterative processes and user feedback – which take advantage of the fact that digital products can more easily be changed even after launch – are less widely used. The reliance on sequential processes – often hinging on approval from higher-ups in what are fundamentally bureaucratic, hierarchical, and often quite political organisations, which can take time to secure – help explain why some projects take longer than they perhaps could have.

Importantly, interviewees in all the public service media organisations have mentioned that the long-term value of their project is not only the project itself but, even more, experimentation and transmission of this knowledge and experience as a kind of pacesetter for the whole organisation. This function is articulated particularly in an organisation like RAI that is – as mentioned by the interviewees – still more of a broadcaster than an integrated media organisation like the BBC or Yle, for example. Also, the joint website project between France Télévisions and Radio France, as well as the videos for the ARD app that are produced by a team formerly belonging to TV, or their planned integrated newsroom, show that barriers between organisations or media are being torn down to adapt to an increasingly digital media environment. However, this can occur at a different pace, depending not just on the actual length of the development processes as we have seen, but also on the projects themselves.

What Factors Facilitate the Development of Digital News in Public Service Media?

Our aim in this report is to better understand how public service media organisations develop new projects and products in digital news (see Chapters 2–5) to meet the challenges they face (see Chapter 1). This chapter identifies factors that interviewees across the different organisations and examples analysed see as facilitating this development. As said from the outset, our focus here is on internal, organisational factors. In many cases, external forces including political discussions around the funding, remit, and role of public service media and pressure from private sector competitors complicate the process of developing digital public service news. (On the other hand, public service media organisations do not face the same pressures on revenues that newspapers do, for example.) Similarly, the development processes we focus on here play out against the background of the wider set of challenges and opportunities that come with pursuing change in large legacy organisations. The organisation, workflow, and content management systems, as well as the values and assumptions, of public service media organisations, still reflect their broadcasting legacy. This provides important assets – reputation, talent, and content – but also sets challenges. Many management scholars argue that past successes can lead to inertia that seriously undermines the ability of organisations to adapt and succeed in the future in a changing environment (e.g. Christensen 1997; Tushman and O’Reilly 2002). Our interviewees recognise this risk. ‘I think one of the difficulties was the change in mindset. We television journalists have always thought from the point of the TV show, and this influences the production process’, says Elmar Theveßen, ZDF. 93 Nathalie Malinarich, BBC, makes a similar point: ‘I think the thing I found most difficult is that the technology here is geared towards TV, and so it was quite hard to adapt it.’ 94

Some of the factors we identify here are foundational, in the sense that they seem essential in order to successfully develop and sustain new digital forms of public service news. Other factors are facilitating – useful, but perhaps not strictly necessary, as they deal with issues that can be addressed in a range of different ways. All public service media organisations need to develop their digital new offerings to serve the public effectively in the future, but there is clearly not one, standard, ‘right’ way to develop, nor is it clear that there are specific solutions that all should strive towards. Instead, what is clear is that all media organisations need to be able to continually adapt to ongoing change. The factors we identify based on our interviews, and the examples analysed as facilitating this, overlap with factors identified in the rich literature on organisational change and innovation. This suggests overlap between how those involved understand the process and how outside analysts understand it. But some of the many factors discussed in management research are more specific than others to news media and to public service. The purpose of identifying them here is to help both those within the news media and outside observers better understand what facilitates the development of digital news in public service media organisations.

Four factors stand out for us as foundational. These are

- strong and public support from senior leadership;

- buy-in from the wider newsroom;