Executive Summary

This will be a critical year for technology companies as they fight a rising tide of criticism about their impact on society – and on the journalism industry. Platforms will be increasingly wary of the reputational damage that often comes with news, while many publishers will be trying to break their dependence on platforms. 2018 will also see a renewed focus on data – as the ability to collect, process, and use it effectively proves a key differentiator. Media companies will be actively moving customers from the ‘anonymous to the known’ so they can develop more loyal relationships and prepare for an era of more personalised services.

Download full report here

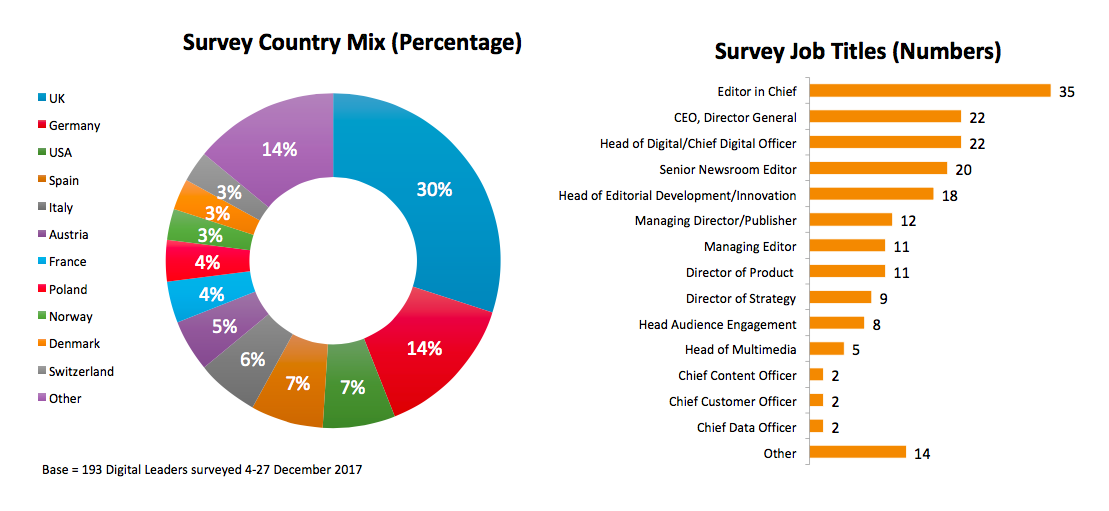

In our Survey of 194 Leading Editors, CEOs, and Digital Leaders

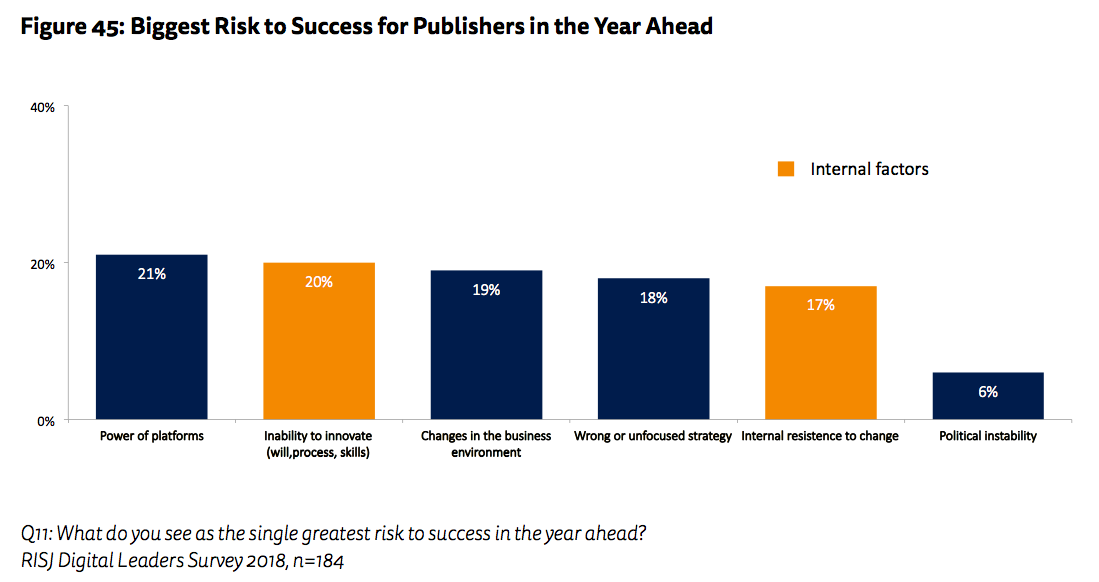

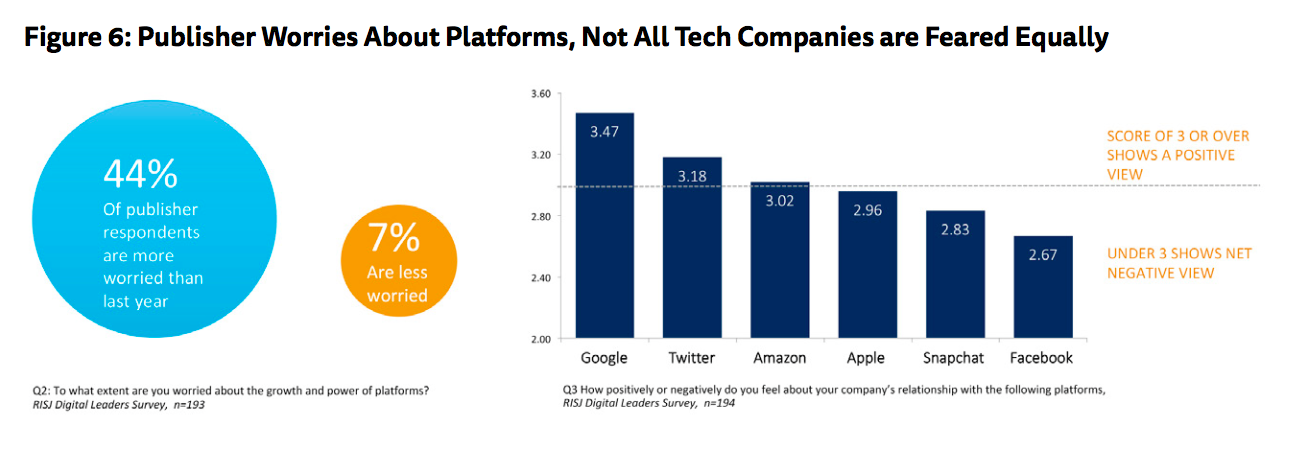

- Almost half of publishers (44%) say they are more worried about the power and influence of platforms than this time last year. Only 7% are less worried. Publishers feel more negatively towards Facebook and Snapchat than they do about Twitter and Google.

- Despite this, publishers also blame themselves for their ongoing difficulties. The biggest barriers to success, they say, are not tech platforms but internal factors (36%) such as resistance to change and inability to innovate.

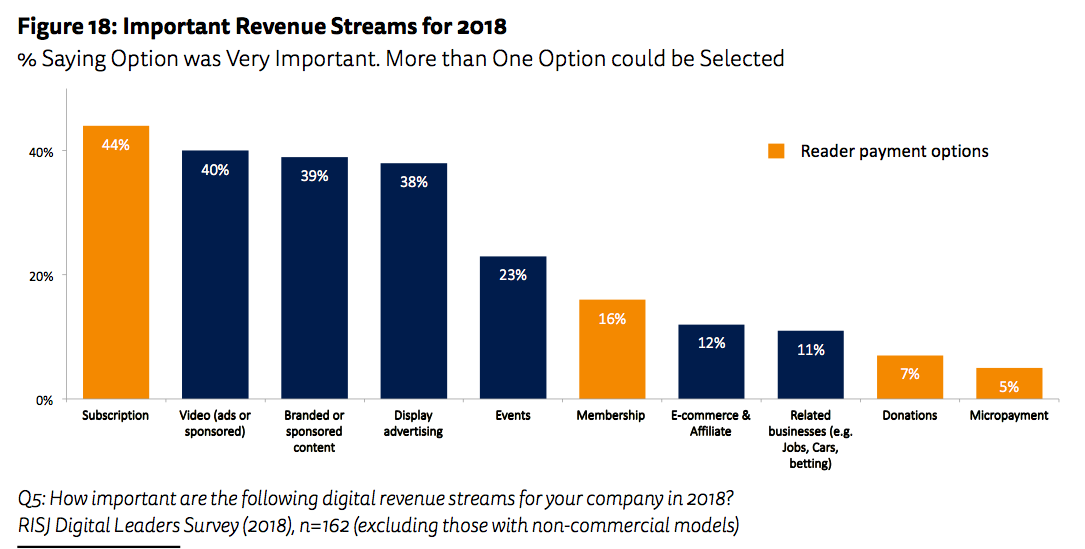

- Almost half of publishers (44%) see subscriptions as a very important source of digital revenue in 2018 – more than digital display advertising (38%) and branded and sponsored content (39%).

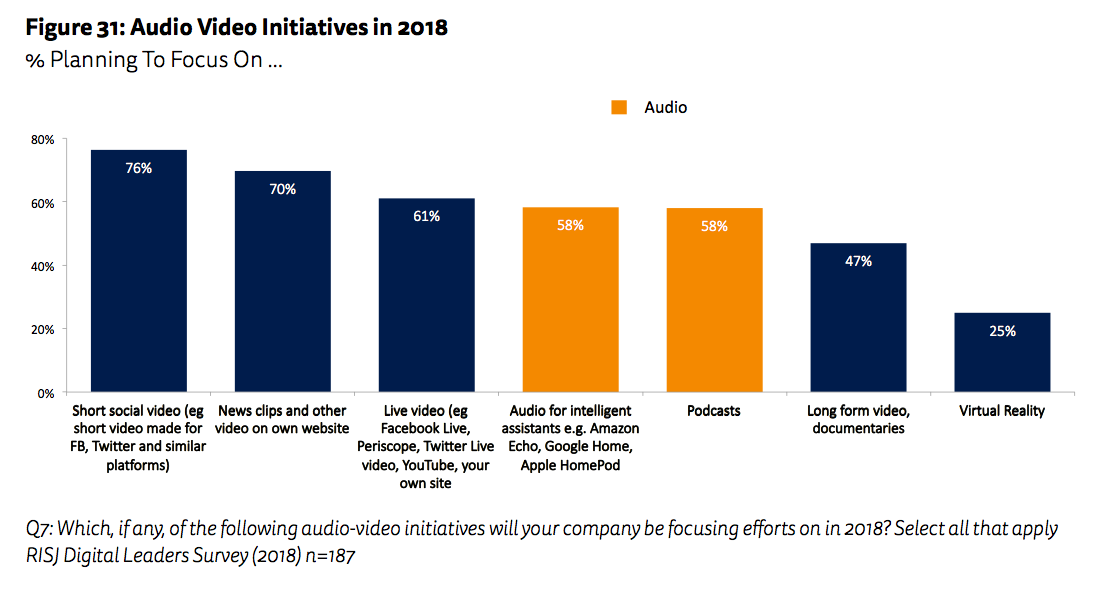

- Expect more audio in 2018: 58% of publishers say they’ll be focusing on podcasts, with the same proportion looking at content for voice activated-speakers.

- Almost three-quarters (72%) are planning to actively experiment with artificial intelligence (AI) to support better content recommendations and to drive greater production efficiency (e.g. ‘robo-journalism’).

How Two Industry Leaders See the Year Ahead

More Specific Predictions

- Investigations into misinformation and the role of platforms intensify, but lead to little concrete action in most countries beyond new rules for election-based advertising.

- Facebook or Google will be regularly accused of censorship this year after protectively removing content, which they feel might leave them open to fines.

- Fact-checking, news literacy, and transparency initiatives fail to stem the tide of misinformation and low trust.

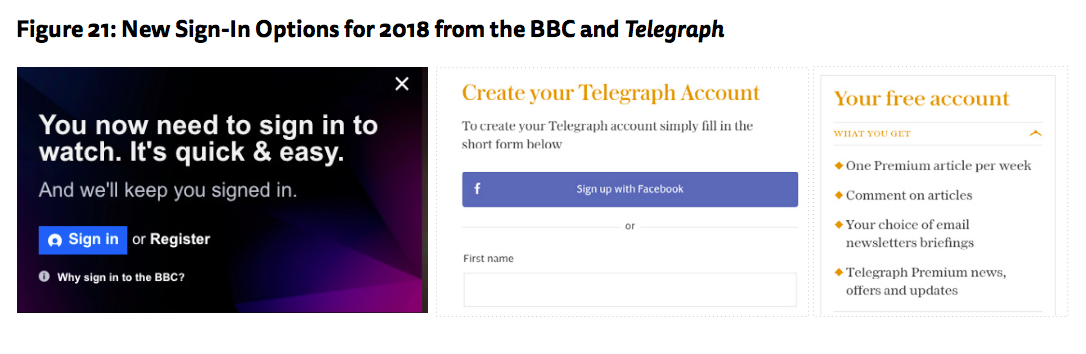

- Publishers force users to sign-in/register for websites and apps – as well as investing heavily in data – to help deliver more personalised content and messaging.

- For the traditional media, we’ll see a growing gap between big brands successfully managing digital transition and the rest (that are struggling).

- More publishers pivot to subscription (or other forms of reader revenue) as digital display advertising declines in importance.

- A number of publishers pivot away from video (… and back to text).

- In social media, we’ll see a further move to messaging platforms and conversational interfaces.

In Technology

- Voice driven assistants emerge as the next big disrupter in technology with Amazon strengthening its hold in the home.

- AR capable phones start to unlock the possibilities of 3D and immersive mobile storytelling.

- We’ll be doing less typing on our phones this year as visual search becomes more important.

- New smart wearables include ear buds that handle instant translation and glasses that talk (and hear).

- China and India become a key focus for digital growth with innovations around payment, online identity, and artificial intelligence.

Looking Back at 2017

This time last year we predicted that the downsides of technology would come to the fore and that we would start to see a backlash against platforms and algorithms.

Facebook felt the greatest heat in 2017 after it emerged that more than 120m Americans could have seen divisive social and political messages posted by Russia during the recent presidential election. Without proper checks, it seems that a foreign power was able to use fake accounts to buy $100,000 worth of political advertising in an attempt to influence a key election.

More widely Facebook’s engagement driven algorithm stands accused of pushing misinformation, propaganda, and polarising content into its news feed from Germany to Kenya to Myanmar. In less than a year, Mark Zuckerberg has gone from being viewed as a tech genius with presidential ambitions to an under-pressure CEO of a company being investigated by governments around the world. The fall out will continue through this year and beyond.

But it is not just Facebook. The infamous Russian troll farm based in St Petersburg created fake accounts on Twitter and Medium while Google has been under fire for surfacing misleading information in search results and allowing ads from big brands to appear in front of jihadist videos and other unsuitable content on YouTube. In the last year it has become clear that what was good for Silicon Valley was not necessarily good for America or the rest of the world and that narrative is likely to gather strength as pressures build around issues such as job displacement from automation and whether tech companies pay enough tax.

Tech-funded initiatives to combat misinformation are underway. Facebook launched its Journalism Project in January 2017 with a focus on news literacy and combatting news hoaxes.It has been re-evaluating how stories are spread and has incorporated independent fact-checking assessments more prominently in the news feed. Google has also been funding fact-checking initiatives and tightening its defences against ‘bad actors’ looking to hack its search algorithm and YouTube platform.

But, as we predicted last year, these efforts so far seem to have had little effect on the extent of extreme and partisan content. As Frederic Filloux of the Monday Note suggests this is partly about scale: ‘It’s like trying to purify the Ganges River, one glass at a time while ignoring the rest of the stream’. There is also evidence that certain fact-checking approaches may reinforce existing beliefs,while the relationship between fact-checkers and some platforms has become strained.

Amid all this, the pressure to regulate or even break up platforms is building in some countries. The US senate is proposing a bill to regulate political advertising on the internet. The UK parliament is investigating whether ‘fake news’ shared on Facebook and Twitter influenced the Brexit referendum, while the Australian competition watchdog is looking at the market power of Facebook and Google with a specific focus on media.

Only in Germany, though, did talk turn to action in 2017. A new law was passed in October that promises to fine tech platforms up to €50m if they fail to remove hate speech or other ‘obviously illegal’ material within 24 hours. This is controversial because US tech companies are effectively being put in a position where they become the arbiters of the limits or otherwise of free speech. The complexities of having private companies handling this role are likely to be exposed in 2018.

Benefits of Social Media

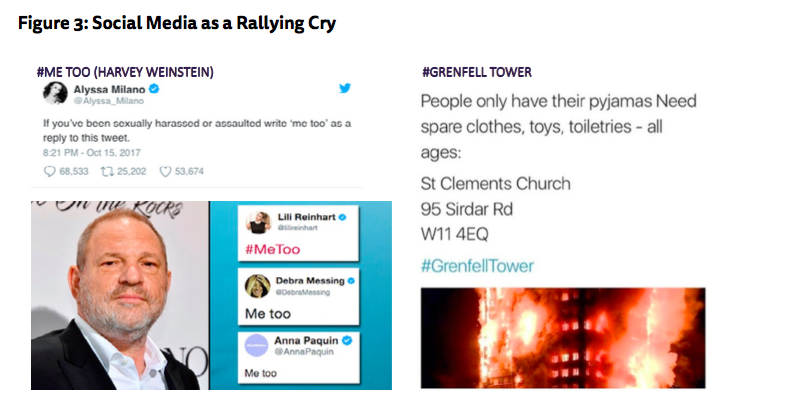

In the interests of balance, it is worth pointing out that two of the biggest stories of the year were driven in a positive way by social media. In October the hashtag #MeToo became a rallying cry against sexual assault and harassment after a tweet by actor Alyssa Milano, one of Harvey Weinstein’s most vocal critics. Within 24 hours, 4.7 million people around the world engaged in the conversation, according to Facebook, with over 12m posts, comments, and reactions. The movement has also inspired offshoot hashtags used by men, including #IDidThat and #HowIWillChange, in which men have admitted inappropriate behaviour.

Secondly, social media hashtags provided a crucial source of information for friends and relatives following the devastating Grenfell Fire in west London, which killed 71 people. They also showcased the generosity of Londoners who offered clothes, shelter, and money.

Journalism Reflects on Biases, Starts to Fight Back

The Grenfell story also provided a wake-up call for journalists in the UK. Residents had warned about the cladding months before, but the story had been ignored by a hollowed-out local media and a national one focused on Brexit. Channel 4 News presenter Jon Snow was visibly shaken when confronted by local residents and later argued that the failure to listen to these warnings showed that the media have ‘little awareness, contact or connection with those not of the elite’.

The issue is highlighted by our news leaders survey this year, with almost half (46%) of leaders saying that they are uncomfortable with the level of diversity in their own newsrooms. Guardian Editor Katharine Viner spoke in November on the growing disconnect between comfortably off journalists and ordinary people and pledged to do more: ‘If journalists become distant from other people’s lives, they miss the story, and people don’t trust them.’ The incoming New York Times publisher has also spoken about the importance of building trust, resisting group think and ‘giving voice to the breadth of ideas and experiences’.

Indeed, the shocks of the last few years are helping many organisations to refocus on quality news and investigations – in part to distinguish themselves from the mass of other information online. To that end 2017 proved to be a vintage year full of reporting that made a real difference. The New York Times exposé on Harvey Weinstein, the ProPublica investigations of Facebook, and the Süddeutsche Zeitung/BBC/Guardian (amongst others) Paradise Papers investigations will all live long in the memory.

Changing Business Models

In terms of revenue, it has been a mixed year with stronger titles pulling ahead while others falter. The Reuters Institute Digital News Report showed a 7% increase in subscription in the US last year led by the New York Times and Washington Post. The Guardian also defied its critics to report 800,000 paying customers, including half a million subscribers or members, and 300,000 one-off donations. For the first time, the Guardian is attracting more revenue directly from readers than from advertising.The shift to reader revenue that we discussed last year is well underway but it will not work for everyone.

In that regard perhaps the least surprising development of the year was the poor business results of some online pure-play news, opinion, and entertainment websites. Heavily dependent on both online advertising and Facebook distribution, BuzzFeed and Vice were reported as missing revenue targets while tech and pop culture site Mashable was sold for a disappointing $50m. This is a trend we first talked about 2016 but in an incisive post Talking Points Memo Editor Josh Marshall sums up the ingredients for a digital media crash that, he says, nobody wants to talk about.

The big picture is that Problem #1 (too many publications) and Problem #2 (platform monopolies) have catalysed together to create Problem #3 (investors realize they were investing in a mirage and don’t want to invest any more).

Expect to see more retrenchment and more pivoting pure players in the coming year.

Mobile and Visual Storytelling

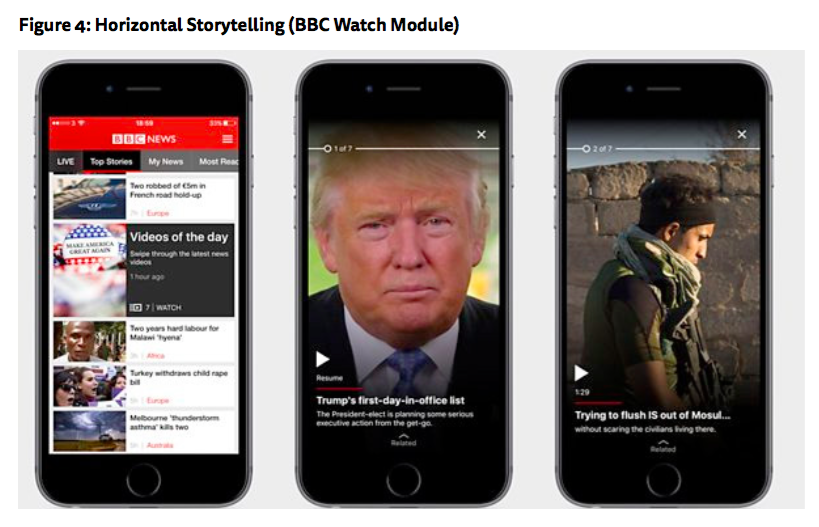

The shape of news has been changing this year with the spread of ‘tap to advance’ horizontal storytelling, which has been well documented by Paul Bradshaw on his online journalism blog.This mobile-friendly way of navigating screens became the default for new mobile launches in 2017, from Facebook’s new ‘Messenger Day’ feature and Medium’s Series to Instagram’s Carousel feature and WhatsApp Status feature, while the BBC news app launched a videos of the day feature using the same approach.

Visual storytelling has continued to become more important, particularly in audio this year: some of radio’s biggest hits during the UK election came through social video with Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour and Nick Ferrari’s LBC interviews. The use of emojis in email storylines and mobile notifications are further ways in which journalists are gaining new skills around visual literacy.

Memes Give us Something to Smile about …

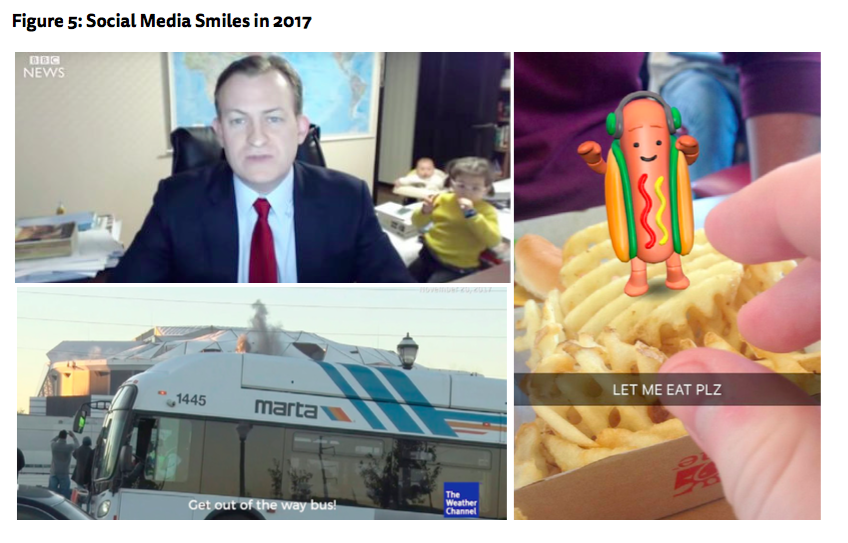

The internet was not all doom and gloom in 2017. It was also the year when – because of social media – we were all talking and laughing at the same things again. Who can forget the Korea expert Robert Kelly’s kids crashing in on his BBC interview, the bus that got in the way of the demolition of the Georgia Dome and Snapchat’s dancing hot dog, the world’s first augmented reality superstar which was viewed 1.5bn times.

We have got through the review of 2017 without mentioning Donald Trump, but it would be remiss not to point out that, against expectations, we predicted last year that he would continue to personally run his fiery Twitter account while in office and indeed that many other politicians would try to emulate him. Amidst all the uncertainly of the year ahead this is one prediction we are happy to roll-over. The sparks will continue to fly from Donald Trump’s Twitter account.

Key Trends and Predictions for 2018

In this section we explore seven key themes for the year ahead, integrating data and comments from our publishers’ survey. For each theme we lay out a few suggestions about what might happen next.

Breaking Publishers’ Dependence on Platforms

This year’s survey reveals high levels of concern about the power and role of platforms amongst around half (44%) of our news executives. This rises to 55% of those from newspaper groups where profits have been squeezed by the increasing share of digital advertising revenues that goes to platforms.

I am especially worried about the share of the advertising market the big platforms have and the lack of alternatives from media companies.

Sergio Rodríguez, Head of Innovation and Digital Transformation, El Mundo, Spain

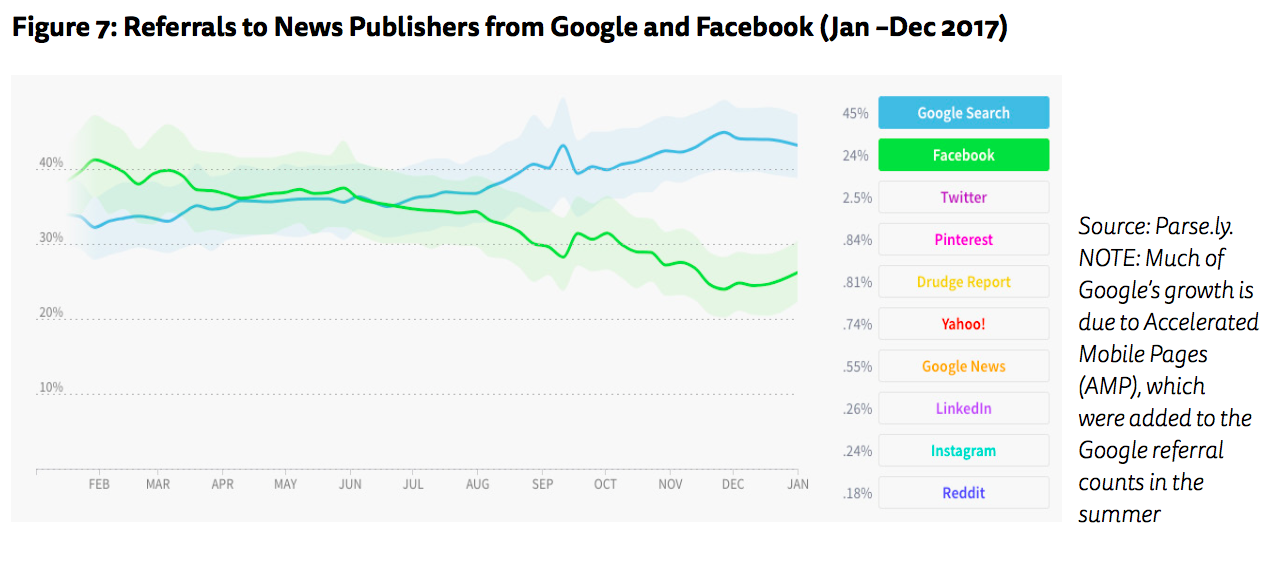

Not all tech companies are viewed with equal concern. On a scale from 1 to 5, there is a more positive view on average of Google (3.44) and Twitter (3.23) than there is of Snapchat (2.82) and Facebook (2.57). Sentiment towards Facebook in particular seems to have worsened following its perceived role in promoting fake news, the lack of promised revenue for video, and a sudden drop in Facebook referrals to many news websites since the summer.

Not all tech companies are viewed with equal concern. On a scale from 1 to 5, there is a more positive view on average of Google (3.44) and Twitter (3.23) than there is of Snapchat (2.82) and Facebook (2.57). Sentiment towards Facebook in particular seems to have worsened following its perceived role in promoting fake news, the lack of promised revenue for video, and a sudden drop in Facebook referrals to many news websites since the summer.

This dramatic switch round reflects increasingly divergent strategies of Google and Facebook, driven by their different business models.

Facebook is trying to maximise time spent within its own website and apps and sell that attention to advertisers. Choking off organic referrals is helping increase the value of paid-for advertising while it is also hoping to take a share of TV advertising budgets with its push into video. Google’s focus largely remains on building business on the open web.

Though tensions remain over whether Google should pay more to content producers, there has been significant movement on key publisher complaints. Google abandoned ‘first-click free’ in 2017, which had the effect of discriminating against subscription-based publications. Many of the European publishers in our survey have benefited from its news innovation fund and publisher outreach programme (DNI), which also helps explain the higher scores for Google.

Google has made a true effort in steering its relationship with the media in the right direction. Initiatives such as the DNI and collaborative product management such as AMP illustrate how publishers and platforms can actually work together.

Spanish publisherFacebook have launched a public charm offensive for news media via the FJP [Facebook Journalism Project] but it seems to be more PR than action. The image of progress without any is probably the worst situation to be in.

UK publisherFacebook is beginning to address the destructive side effects its platform has on the news ecosystem. And the first Google funded projects that try to increase digital revenues for publishers enter the marketplace.

Götz Hamman, Head of Digital Transformation, Die Zeit

Facebook’s new initiatives will take time to play out but many publishers still see the company as arrogant and high-handed, encouraging new content types such as live video – only to change course and withdraw funding. This ‘fail fast’ experimental approach is part of Facebook’s DNA and makes sense from a product and engineering perspective, but is creating significant tensions with publishers who take much longer to ramp up/down content initiatives.

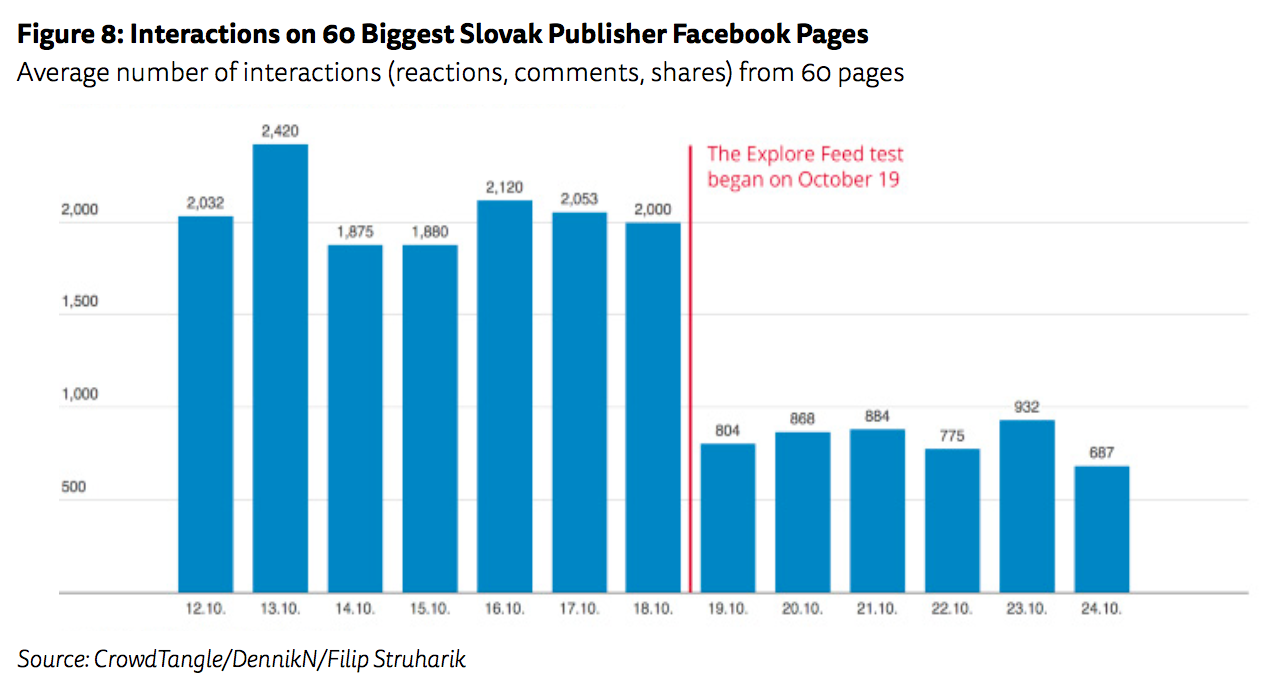

One example of this came in the autumn when, without warning, Facebook moved all publisher-posted content away from the news feed – which users see by default – to a new Explore Feed in six countries (Slovakia, Sri Lanka, Serbia, Bolivia, Guatemala, and Cambodia). For major Slovakian news sites, this meant an overnight 400% reduction in interactions and two-thirds loss of reach.

In many developing countries, like Guatemala and Cambodia, there are fears that the loss of Facebook traffic will stunt the growth of independent media that had started to provide a balance to state owned media and also to extreme perspectives that have become rife in many parts of the world.

In particular, in developing countries like Myanmar and Cambodia where Facebook is the internet, basically … this is a big threat to real democracy and freedom of speech.

Norwegian publisher

Facebook says there are no ‘current plans’ to further restrict publisher content in the news feed or roll these experiments out to other countries. But George Brock of City University suggests that Facebook may be in a weaker position than it seems:

If Facebook continues to pretend that its business model doesn’t have bad consequences, a gap will eventually open for a rival to combine good technology with editorial qualities, which do not pretend that all communication and ‘connection’ is inherently good and problem-free.

From our survey it is clear that many publishers still feel that platform companies need to do much more to face up to their wider responsibilities. Advertisers are demanding greater transparency over measurement and for more protection for their brands. Politicians, regulators, and ordinary users will be adding to that pressure too. Something significant is likely to give in 2018.

Likely Developments

Facebook Damps Down News in Feeds

We don’t expect Facebook to remove posts originated by brands (using page posts) from the news feed but we can expect the core algorithms to quietly pay less attention to this type of content. In combination with increasing exposure and attention to fact-checking this is likely to ease the misinformation problem but at the expense of reducing exposure to a wide range of legitimate news. One alternative option for Facebook might be to remove in-feed-based news content but to replace it with a news trending module linking to the Explore section (like the Apple News widget). Either way, Sarah Marshall, Growth Editor Condé Nast International, is one of our respondents who is expecting ‘traffic from Facebook to drop to news sites’ in 2018, in developed markets at least.

More Publishers Pull Back from Platforms

A key theme from many of the comments in our survey was the desire to take back control. ‘We’ve been playing their game for a long time with much risk and not much reward,’ says says one respondent working from Germany. Expect more news organisations to pull out of deals with Facebook, Apple, and Snapchat that they consider are not delivering sufficient financial return, focusing instead on building more direct readership. This won’t be universal but a better balance will emerge in 2018.

Armies of Internet Moderators Employed by Tech Platforms

Platforms will be forced to take on thousands more extra editorial and policy staff – either because of regulation (Germany) – or as a way of staving off regulation (UK).

YouTube alone will be employing a total of 10,000 human moderators by early 2018 and these will be assisted by algorithms that flag potentially worrying content. No need to worry just yet about humans being replaced by computers in the age of automation.

Platforms Accused of Suppressing Free Speech

Facebook or Google will be regularly accused of censorship this year after protectively removing content which they feel might leave them open to a big fine. Indeed Facebook and Twitter have already removed content from a far-right member of the German parliament, for alleged incitement, as the new laws covering social media platforms come into effect. Elsewhere, Facebook has started the year by removing the accounts of Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov because he had been added to a United States sanctions list – which would have exposed the company to financial penalty. The lack of clear and transparent rules about which content – and which accounts – should be removed will become an increasingly thorny issue for platforms in 2018 and an increasing source of tension between the US and undemocratic regimes. Accusations of double standards by American companies will be hard to counter, particularly if the US president himself continues to promote inflammatory material via his Twitter account. Campaigners argue that Silicon Valley companies should not be forced to be the arbiters of free speech or human rights and argue for new independent oversight.

Revelations about manipulation of platforms in the US electoral process has brought home not only how problematic the role of the big platforms is, but also how challenging the issues are to fix in a way that is in tune with our core democratic values.

News chief at a leading US publisher

More Talk of Regulation and Platform Break up, But Little Action

Beyond new rules on political advertising, there is likely to be little concrete action against platforms in 2018. Scaled-up moderation and a continued charm offensive by platforms (more money for news literacy, innovation) is likely to head off extreme regulation, not least because there is little agreement on what should be done. With only a year to run, the European Commission may find it is easier to focus on headline-grabbing initiatives – such as making platforms pay a bigger share of taxes on European sales.

Restoring Trust in the Era of Fake News

‘Fake news’ was the Collins dictionary phrase of the year in 2017, just as experts (Wardle) warned that the term has become misleading and unhelpful. As our own research (Nielsen and Graves, 2017) has shown, from an audience perspective, the term covers a multitude of sins – crystallising audience concerns about biased and shoddy journalism, political spin, misleading online advertising, as well as deliberately fabricated stories distributed via social media. There will be no quick solution to this complex mix of different but related problems.

Although many of these concerns (spin, propaganda) have been around for decades, it is clear that digital and social media have fundamentally changed the rules of the game. Kevin Kelly, co-founder of Wired magazine, points out that: ‘Truth is no longer dictated by authorities, but is networked by peers’. As a result there is less faith than there used to be in traditional media brands. At the same, the internet has exposed citizens to a vast array of new perspectives. Facts, alternative facts, and counter-facts now sit side-by-side online (for example, in a social media feed) in a way that is often confusing to audiences.

So far attempts to tackle these problems (fact-checking, greater transparency) have assumed that it is possible to rebuild public trust in the media. But as we suggested in our recent Reuters Institute report Bias, Bullshit and Lies (Newman and Fletcher, 2017), it may be hard to persuade people of facts that run counter to their own entrenched beliefs however clearly or transparently stated. Greater scepticism towards the facts is the inevitable consequence of exposure to a wider range of perspectives. In itself this may not be a bad thing as long as it is supported by better source labelling, signals of quality, and improved news literacy.

Likely Developments in 2018

Platforms Deploy MAXIMUM Technology – But Can’t Fix the Problem

The damage that has been created by misinformation, propaganda, and abuse represents an enormous challenge for platform companies as they try to balance their commitment to maximum freedom of expression with a need to rid their services of damaging content. For the first time engineers have begun to realise the consequences of what they have created, but also that technology on its own cannot solve the problem. Expect the deployment of a range of targeted new processes and algorithms to spot different kinds of abuse, and flag these to human moderators. Much will be made of the way in which these algorithms can learn from these human interventions (AI) and become smarter and more self-sufficient.

But we’ll also be seeing more examples of how technology can create fake news. The University of Washington’s synthesising Obama project took the audio from one speech and used it to animate his face in a different video with incredible accuracy. Canadian start-up Lyrebird is working on audio impersonations. Whilst these are being created for entirely legitimate purposes, these examples show how voice morphing and face-morphing could, in the wrong hands, produce realistic fabricated statements by politicians or other public figures.

Fact-Checking Matures; the Rise of ‘Alternative Fact-Checking’

This year, we’ll also see more focus on challenging inaccurate information in third-party platforms. Platform (and government) funding of independent fact-checkers will increase in 2018, along with technical (semi-automated) solutions to help them do a better job. Visibility will increase in social networks and search engines as data-driven experiments reveal where and when they can have most impact. With their increased profile, expect (a) more robust challenge of fact-checking judgements from those being judged, and (b) the setting up of ‘alternative fact-checkers’.

In December, the Weekly Standard became the first conservative US publication to join the list of verified fact-checkers. The magazine has been dubbed a ‘serial misinformer’ and is the first explicitly partisan organisation to join the effort. Expect more rows over who is ‘allowed’ to be a fact-checker and the first ejection from the approved list for breaching agreed rules.

Better Labelling and Prominence for Authoritative Brands

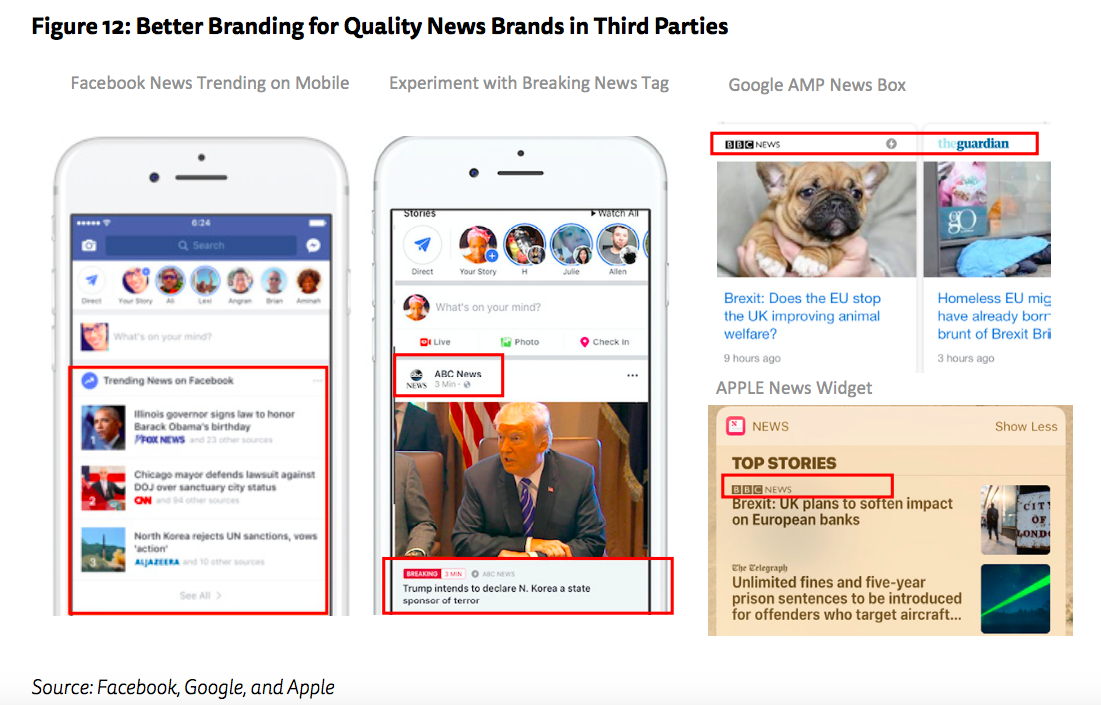

In the fragmented world of the internet, the focus is shifting from figuring out what to believe to who to believe. The ability to identify trusted brands or people quickly will be at the heart of healthy information ecosystems but we are still some way from that. Reuters Institute research showed that less than half (47%) typically recognised the news brand that had created the content when accessing news in Facebook, Twitter, or Google (Kalogeropoulos and Newman, 2017).

By the end of 2018 expect significant progress in this area. Google says it will do more to surface more high-quality, credible content on the web, which in turn requires better tagging and description of content at source. The Trust Project is already providing indicators about ethical standards and journalistic expertise, which will start to be integrated into algorithms this year. At the same time, platforms will increase the space given to news logos to enable familiar brands to be more easily picked out and new tags to describe content such as breaking news or analysis.

Most of these examples of more prominent branding are currently experimental, mobile only, or just applied in a few countries, but expect to see them to be rolled out in a more consistent way in 2018 across platforms and territories including Facebook’s news feed itself.

More News Literacy on the Way …

Education around how to avoid fake news will be part of the story this year. There will be well-funded initiatives, campaigns, and programmes to help, in Dan Gilmor’s words, ‘upgrade ourselves to be active users of media and not just passive consumers’. The BBC has set up a new website for teenagers and from March will be taking top news presenters like Huw Edwards and Amol Rajan into schools, providing video tutorials and launching a ‘Reality Check Roadshow’.

Social Media and Messaging in 2018

Away from fake news and relationships with publishers how can we expect the social landscape to change this year?

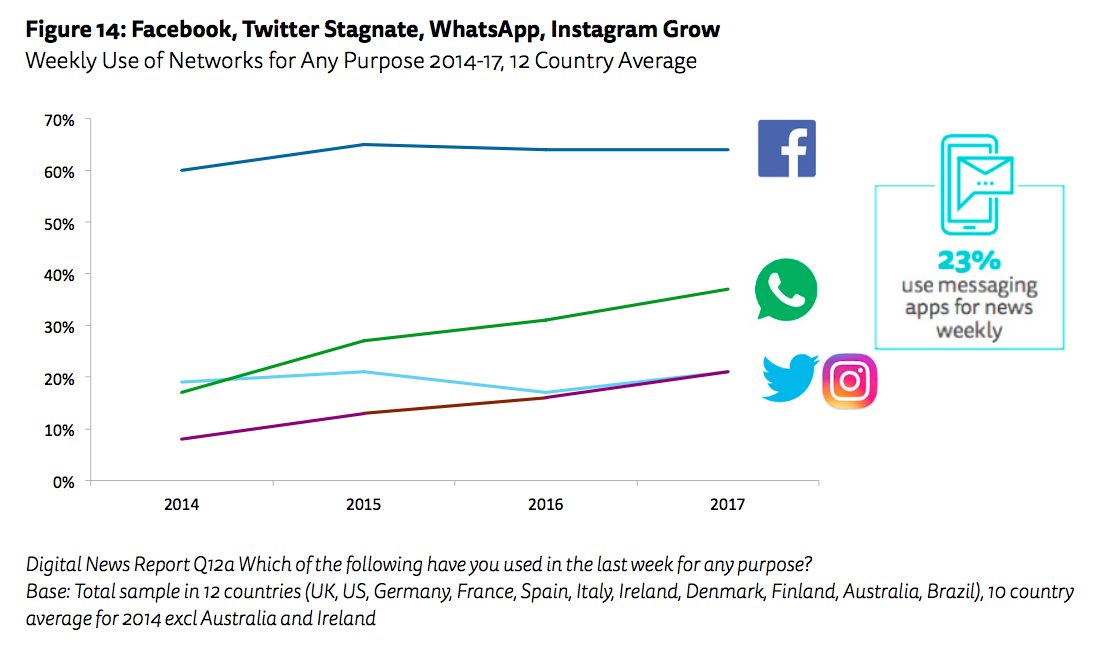

The Reuters Institute Digital News Report is one of many surveys showing Facebook usage is high but stagnating (see the next chart). In developed markets at least, we have reached ‘peak Facebook’ and this is why the company will be talking less about reach and more about loyalty and time spent in the coming year, even as it continues to grow Instagram, Messenger, and WhatsApp.

Another sign that we may have passed the peak has been the decline in participation on Facebook. This reduction in personal sharing is sometimes called the ‘context collapse’ and is partly related to our unwillingness to share openly in a network that includes so many different types of friends. As a result, some sharing of personal content has shifted to smaller, ephemeral, or more closed communities, especially for video and pictures. In our Reuters Institute data, messaging platforms like WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger are growing rapidly in general but also for news, while Snapchat resonates most with 18–25s. Instagram has also been one of the fastest growing networks over the last two years as it moves to capitalise on new mobile behaviours and richer story-based formats. Facebook owns all of these companies except Snapchat and continues to dominate the social sphere (80% touch a Facebook product weekly according to Digital News Report data). It has also started to integrate its services more closely, using this ‘data lake’ to offer advertisers unprecedented opportunities for micro targeting of consumers.

Meanwhile, Twitter continues to struggle for growth though it has been making attempts to improve usability, adding algorithmic selection of content, better threading and a longer character length. But will this be enough to save it?

Developments to Watch in 2018

Targeting the Tweens

One strategy for increasing reach is to focus on under-13s, who aren’t officially allowed a Facebook account. Research in the US shows that three out five parents say their under-13s use messaging apps, social media, or both. Two-thirds (66%) of tweens have their own device, with 90% having access to a shared one. (National Parent Teacher Association study working with Facebook).

FB Messenger Kids will be rolling out through 2018, offering a service for this age group where parents must approve and verify all new contacts, though they are not entitled to see the content itself. The new app is interoperable with the main Messenger service, so adults don’t have to download the kids app. Tweens don’t automatically migrate to Facebook, but the idea is to start them early. It is possible to imagine this eventually expanding into a much wider platform for age-appropriate entertainment and education content. With many of the FB management team now parents themselves, it is not surprising they are focused on creating a service that works from cradle to grave.

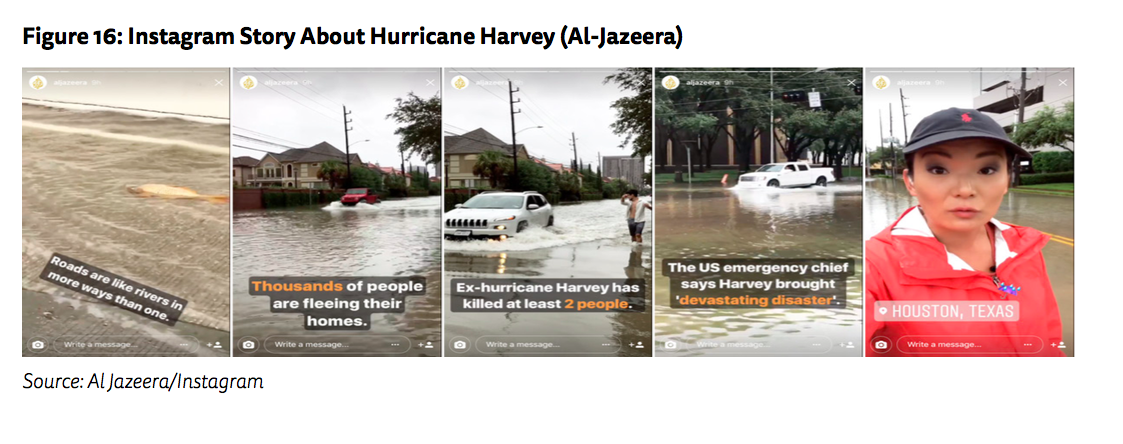

Mobile Story Formats Hit the Mainstream

With over 250m users, Instagram stories have already surpassed Snapchat in popularity. Effectively these are easy to create slideshows that you can animate (add filters, effects, text, and stickers). Users can mix pictures and videos and you can also create live video stories, which can be archived for later. Journalists are increasingly using these powerful tools to tell their own mobile stories.

We going to see more of these visual, swipeable story formats in 2018. Facebook is boosting the prominence of its own stories and will also enable cross-posting of Instagram ones. Re-engaging user-generation in this way could help solve the problem of context collapse mentioned above. Asian tech platforms like China’s Sina Weibo are getting in on the act while Kakao in Korea has its own Stories app.

Now Facebook has proved how easy these features are to copy (from Snapchat), expect to see more mainstream media companies deploying them within their own mobile websites and apps – as well as using third-party platforms that offer these formats. Organisations like the New York Times are investing heavily in Snapchat and Instagram and Alf Hermida of the University of British Columbia says journalism organisations can learn much ‘by investing in novel and emerging approaches to storytelling’.

Social Challenge to Traditional Television Intensifies

Mark Zuckerberg is on record as seeing ‘video as a megatrend’, but plans to rival YouTube or Netflix off the back of the news feed have not yet worked out. Facebook Live has not been as popular as hoped while early attempts to create original online shows have failed to turn Facebook Watch into a must-visit entertainment destination. But Facebook’s answer to these setbacks may be to get more serious about video. 2018 is likely to be a pivotal year for Facebook’s ambitions in this area, as well as for other Silicon Valley challengers.

Developments to Watch

Facebook Becomes a Media Company

Facebook has pledged to spend billions of dollars advancing its TV ambitions. It’s looking to commission bigger budget shows in 2018 that make more impact. Facebook is talking about investing in ‘hero shows’, perhaps even owning programme rights for the first time, which would severely weaken its claim not to be a media company. In this respect, it may be looking to compete more with Netflix and Amazon than with YouTube. In turn this will require shifting consumer expectations. Long-form linear content is not an obvious fit with social media and is still mainly watched on TV-sized screens.

Sports Rights as Short Cut to Success

The quickest way to changing habits will be to acquire exclusive must-see content. That is likely to mean sports. Amazon has acquired rights for Thursday night NFL football this season to help build its Amazon Prime brand. It also outbid Sky for the UK rights to the tennis tour for around £10m a year, its first major acquisition outside the US. Facebook has already tried to buy IPL cricket in India but lost out to Rupert Murdoch’s Star network and is now reportedly showing interest in the mobile rights for NFL (American football), which expire at the end of the season.

A looming battle is expected for Premier League streaming rights for the period 2019–22, with Facebook, Amazon, and Google all likely to be in the frame. The auction, which includes UK and international rights, is due to be completed by February this year. All this is likely to mean even more money for sports clubs and perhaps joint bids between tech companies and media businesses to keep the costs affordable.

Online Publishers Lose Out, Pivot Away from Video

With Facebook’s attention shifting towards television and towards entertainment and sport, existing online publishers could be left in the lurch. Partners like BuzzFeed, Mashable, Attn and Vox Media have benefited from direct payments from Facebook to create original online content, but Facebook is on record as wanting to reduce those payments over time and is already restructuring deals. Ad revenue is still limited though new formats are due to be tested within the Facebook Watch destination in 2018.

Many publishers will need to decide whether producing lifestyle or unscripted video for Facebook still makes sense. Video production is expensive, logistically difficult, and hard to scale. Even basic news production will need re-evaluating: with little prospect of pre-roll ads in the news feed, versioning video for Facebook can provide reach but little revenue.

We will see a scaling back of investment by publishers in syndicated short-form video. A previous assertion that syndication and social growth will ‘pay off in the end’ will be questioned more than it has in recent years.

UK publisher

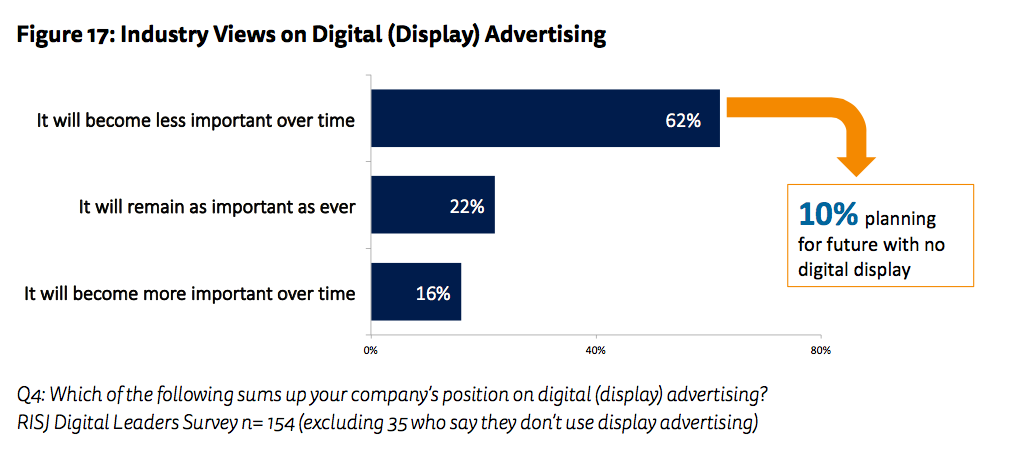

Shifting Business Models: From Advertising to Reader Payment

Our digital leaders survey shows a clear but not universal view that advertising will become less important over time (62%), with than one in ten (10%) saying they are actively planning for a future with little or no display advertising. This is a significant turnaround. Adjacent display worked well in print, was largely ignored on the desktop, and has become irrelevant on a mobile screen.

The economics of supply and demand has driven down prices, ad fraud is rife, and ad-blocking is widespread. And, as we’ve already noted, the big tech platforms are taking most of the new digital advertising money because of their ability to target any audience efficiently and at scale.

As New York Times CEO Mark Thompson suggested earlier, the continued rapid decline in both print and digital advertising revenues will lead to growing ‘economic distress’ this year. This will apply to many newspaper groups but also to venture capital-funded pure-players that may have leaned in too far with a distributed model.

As New York Times CEO Mark Thompson suggested earlier, the continued rapid decline in both print and digital advertising revenues will lead to growing ‘economic distress’ this year. This will apply to many newspaper groups but also to venture capital-funded pure-players that may have leaned in too far with a distributed model.

Against this background it is not surprising that commercial media companies are looking at new approaches for 2018 and in particular towards different forms of reader payment. More publishers said digital subscription (44%) would be a very important revenue stream than any other option. Membership, which we defined as a regular fee paid by loyal users to keep the site free for all, was considered very important by 16% and one-off donations by 7% of commercially funded respondents.

For now it seems that many publishers are hedging their bets. The majority of print and digital-born publishers in our survey are pursuing multiple revenue streams, with an average of six different options viewed as or very or quite important.

[This year] seems like a year when media companies that are under increasing financial pressure go back to the basics of their business to find new revenues. I think that increasingly they are realising that distributed content, video, VR and AR are not the one-shot saviours that people hoped they would be. The real value in this business is the same as it ever was – great journalism. The trick is getting people to pay for it.

Digital Head of UK publisher

The shift to subscription is driven by a combination of desperation and hope. The success of big US publishers like the New York Times (2.3m digital subscribers) and the Washington Post (which has doubled digital subscriptions in 2017 to 1 million), as well as several European titles, including both up-market general interest papers like the Helsingin Sanomat in Finland, tabloids like Bild in Germany, and local papers like those owned by Amedia in Norway, has inspired others to switch the focus to reader payment.

Research shows that some young people, perhaps sensitised by Netflix and Spotify subscriptions, are more interested in paying for news than we had thought. De Correspondent’s success in funding distinctive, independent journalism by attracting 60,000 paying ‘members’ shows that the model can work in small countries and with non-traditional brands. One-off donations to the Guardian in the last year (300,000) have brought in millions of pounds of new revenue. Its paying membership option reduces dependence on advertising while keeping the benefits of open access.

On the other hand, there are still many reasons to be cautious. Most people have no intention of paying anything for online news today or in the future. In practice there will be no one-size-fits all model for reader payment or for business models in general. In our survey, those focusing on subscription tend to be in the richer parts of the world like the US, Germany, and Nordic countries. Publishers from Southern and Central Europe and from Asia and Latin America recognise the need but find it much harder to see how in the short term they can move away from their dependence on advertising.

Elsewhere, there is another more practical concern. Small publishers with an existing subscription business like Follow the Money in the Netherlands worry that they might lose out if more publishers launch paywalls.

More publishers will focus on reader revenue … but will the number of readers who are willing to pay increase? Otherwise we will end up competing for the same subscription money.

Jan-Willem Sanders, publisher, Follow the Money

Developments to Watch in 2018

Two-Tier Information System Emerges

The move to reader payment is a challenge to the idea that the web can open up information to all – and in the process drive democracy and progress. If more high-quality content disappears behind a paywall, there is a danger of widening the current disconnect between the elites and the rest of the population. We could potentially see a situation where those who can’t afford to subscribe are subject to the lowest quality journalism and the highest amount of misinformation – in turn leading to more polarisation and division. In 2018 we’ll see far greater awareness of this problem and some attempts to tackle it.

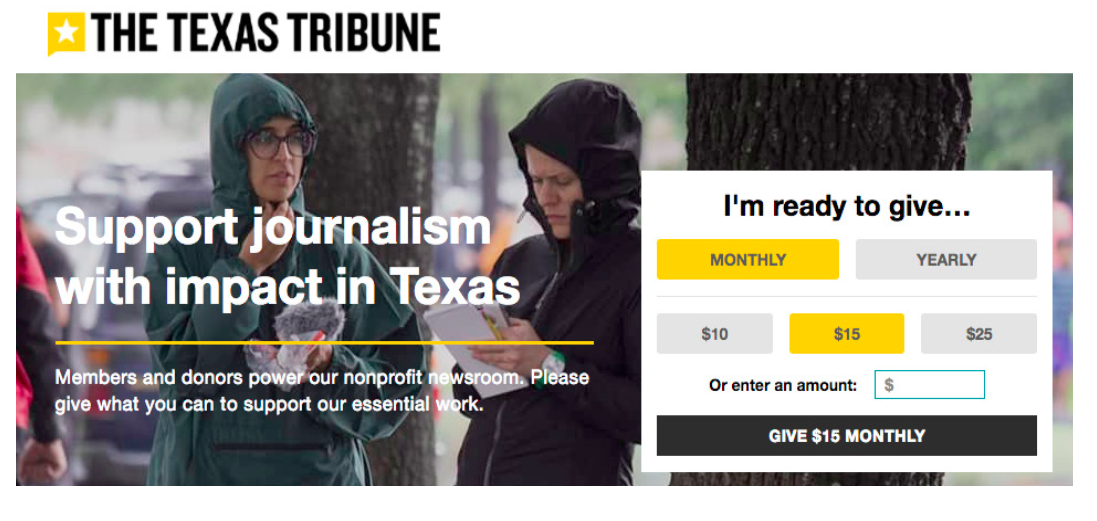

Expect to see media companies setting up more student and library offers – and to extend schemes that allow others to sponsor subscriptions for those that can’t afford them. But we’ll also see more examples of publications trying to engage communities to pay something to keep content free for all, such as the Guardian and Texas Tribune.

Battle for Global Subscribers, Bundling Drives Numbers

Up until now, most attention has been focused on getting domestic customers to pay, but as that gets harder the focus will switch to an international audience with differential (cheaper) pricing to drive numbers.

Paywalls are being tightened. The New York Times has recently moved from ten free articles a month to five and new trial offers, sampling, and pricing options are being prepared. The Times has set a stretch goal of 10m subscribers by sometime in the 2020s and that will require a much more international and multilingual product with more local journalists for customisation. Another key weapon in the battle for paying eyeballs will be bundling. Here, the Washington Post’s partnership with Amazon Prime gives it an enormous advantage at home as well as abroad. Local newspaper partnership will also play a role. Hundreds of local newspapers offer a Post digital subscription as part of a bundled national/local package.

Expect to see more bundling deals in 2018 and especially with utility, phone, and pay TV companies looking to provide more lock-in value for customers.

Public Service Media Under Pressure

Concerns about misinformation and market failure in commercial local news provision should be rallying support for public media, but populist politicians and strains on public funding are pushing hard in the opposite direction. It is highly possible that a referendum in Switzerland in March to scrap the compulsory broadcasting fee will pass – reshaping the media landscape. Populist pressures are building elsewhere with a right-wing Danish party proposing scrapping of the licence fee there. In Eastern and Central Europe public broadcasters increasingly serve as promotional arms of their governments. In the UK, incoming BBC News chief Fran Unsworth is looking at cuts of around £80m over five years. Licence fee money has already been top-sliced to pay for local journalists in newspaper newsrooms.

I am increasingly worried there may be little long-term survival for most commercial media, but that they may try to drag public service media down with them in an effort to gain traction for paywalls, leaving the public with no strong media at all in the longer term.

UK based publisher

Advertising Improves (a Bit), Tech Giants Block Ads

Just when we thought digital advertising was finished, 2018 could see a partial revival of its fortunes. The advent of browsers that automatically block overly intrusive advertising is the culmination of several years of work from the Coalition for Better Ads, an alliance of platforms, industry bodies, advertisers, and publishers. On the way out are ads that flash, autoplay sound and video, and those that take over the page. Retargeting of ads across websites will also become much harder in Europe after GDPR regulations come into place in May. Worries about ads being placed next to poor-quality content could also help publishers sell premium advertising either on their own or in alliance with others. More publishers are likely to pull away from automated ad exchanges to focus on higher quality premium experiences.

The Chrome web-browser incorporates ad-blocking by default from mid-February. By addressing the worst abuses, Google hopes it can stop users from downloading stronger third-party tools (e.g. Brave and Cliqz) that block its own ads and tracking systems. Apple, which doesn’t have a business model based on ads, is going even further – offering users the opportunity to turn on ‘reader view’ by default. This strips out advertising, branding, and contextual related links, which may have a more detrimental effect on publishers.

Overall digital advertising continues to grow strongly, with Facebook and Google attracting 84% of global spending in 2017 according to a forecast from Group M.The greatest threat to the so-called duopoloy looks set to come from Amazon in 2018. Brands say they are planning to invest more in Amazon ads around its shopping search engine and live streaming of NFL games opens up new advertising opportunities. Amazon will overtake Twitter and Snapchat in advertising revenue in 2018.

Consolidation, Partnership, and Media Takeovers

We’ll see more mergers and acquisitions in 2018 as publishers try to build scale and make their businesses more efficient. That will also mean fewer journalists. As one example, Meredith’s recent purchase of Time Inc should produce savings of around $500m in the first two years by trimming overlapping costs and closing some titles.Consultant Kevin Anderson expects to see legacy players such as broadcasters with deep pockets up snapping up digital-born operations: ‘There are simply too many players chasing a limited audience and advertising pool to survive’. But the year ahead will also see a new round of publisher alliances ‘to provide meaningful alternatives to the tech titans’, predicts one very senior news executive who responded to our survey. These could be around advertising alliances (Portuguese publishers, Schibsted in Norway and Sweden), content (BBC and local news), selling subscriptions (Washington Post and local papers), or technology solutions (Washington Post and Globe and Mail in Canada).

Data, Registration, and New Permissions

This could be the year when media companies recognise how critical data will be to their future success. In our survey, almost two-thirds of publishers (62%) said that improving data capacity was their most important initiative for the year ahead. Closely related, over half of publishers (58%) said registering users was considered very important, with another quarter (26%) saying this was quite important. Moving audiences from the ‘anonymous to the known’ is critical for publishers looking to create a deeper relationship with audiences and to provide more personalised and relevant services. This is the next battleground for media – and having the right data infrastructure and skills will be the key to making it work.

Developments to Watch

If Not Subscription, Then Registration

As one example, UK publisher the Daily Telegraph wants to grow registered readers to 10m as it moves away from a mass reach strategy to one based on maximising revenue from a smaller number of logged in users. ‘A registered reader – as opposed to an anonymous one – is far more valuable to the business than the vast majority of our audience’, according to the Telegraph’s CEO, Nick Hugh.

The BBC has started to force all users of its TV iPlayer service to register before viewing programmes. This has already delivered 23m registered users, creating the conditions for BBC News and Sport to also deliver more personalised recommendations on the website, in the app, or via mobile notifications. ‘News apps need to find better ways to use contextual signals from a device to take into account not only relevance but also time of day and location/activity, and to balance that with the urgency and or importance of the push alert’, says Natalie Malinarich, BBC Mobile and New Formats Editor, in a piece for the Nieman Media Lab. Elsewhere (e.g. Norway) publishers are looking at collective national registration schemes to provide better scaled data that can compete with Facebook.

The Impact of GDPR

One additional factor pushing sign-in is upcoming European regulations that require publishers to gain explicit permission from readers to contact them. Failure to opt out will no longer be sufficient consent under the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which comes into force in May 2018.

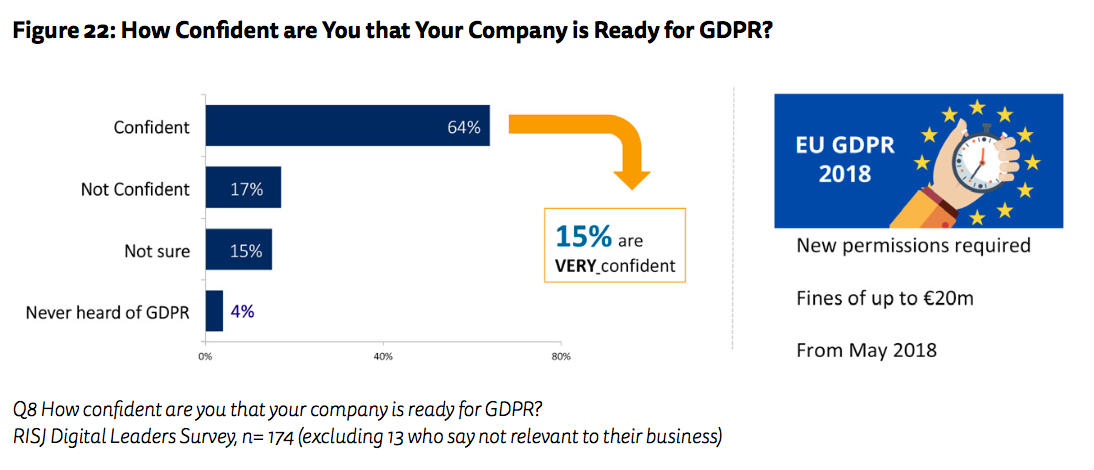

Effectively this means that from early this year many publishers will have to ask again for consent around various permissions including emails, profiling customer’s data, or sharing it with third parties. The fear is that users will withhold these permissions, affecting revenue or even a publisher’s ability to personalise content.

Publishers will also be required to provide mechanisms (e.g. a Facebook style customer preference centre) for users to check and change permissions. A requirement for clearer and simpler privacy policies and the right to transfer or have data deleted is also part of the package. As with much new regulation, it is not entirely clear what compliance will mean or how strictly it will be enforced. But with fines of up to €20m, the stakes are high. Despite this, our leaders’ survey reveals that the majority believe they are well prepared for the change (64%). Around a third say they are either not confident (17%) or not sure (15%).

The biggest impact of GDPR could be on consumer experience, with irritating messages asking for permission and new opportunities to forget passwords. In terms of the economic effects, GDPR could favour premium publishers that have enough trust to obtain consumer consent, leaving other sites struggling with less valuable advertising (lower CPMs ) and a loss of and economic competitiveness.

Newsrooms Embrace Artificial Intelligence

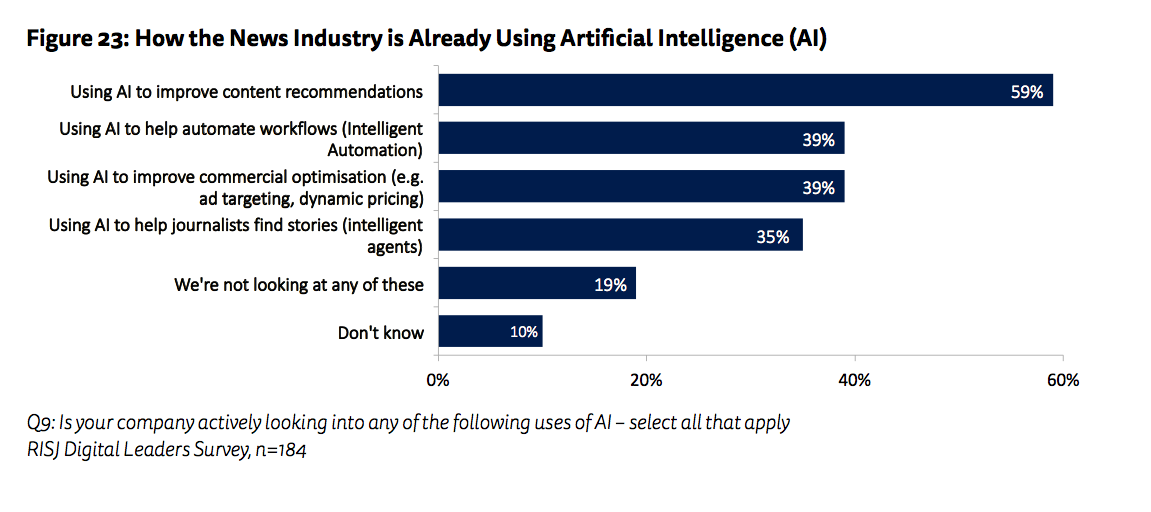

With tech firms betting their future on AI, publishers are also looking to understand how this range of complex technologies could be deployed in their businesses. Surprisingly, almost three-quarters of those we surveyed said they were already using some kind of artificial intelligence, by which we mean computers that learn over time – independently – to improve outcomes. Respondents told us about projects to optimise marketing, to automate fact-checking, and to speed up tagging and metadata. Many of these are R&D projects at this stage but expect a significant number to move into production over the next year.

Developments to Watch

Developments to Watch

Computer Driven Recommendations

One of the most likely uses of AI for news publishers is in driving better content recommendations (59%) on websites, via apps, or through push-notifications. Onward links are currently added manually or with simple CMS logic, with most users seeing the same stories, but AI could change this. A new recommendation service called James, being developed by The Times and Sunday Times for News UK, will aim to learn about individual preferences and automatically personalise each edition in terms of format, time, and frequency. The algorithms will be programmed by humans but will improve over time by the computer itself working to a set of agreed outcomes. The Swiss quality newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung (NZZ) has also been working on AI recommendation and is developing algorithms that are not optimised for clicks but to uphold journalistic standards. These combine ideas of general relevance and personal relevance so individuals are not caught in a filter bubble but are still exposed to more content that they might enjoy.

Assistants for Journalists

Personal Assistants for journalists disappeared in a round of cost cutting in the mists of time, but they’re making a comeback in the form of AI bots that can manage diaries, organise meetings, and respond to emails. But some go much further. Replika is an AI assistant that, with a bit of training, picks up your moods, preferences, and mannerisms until it starts to sound like you and think like you. In the future, maybe it could mimic your posts on Twitter and Facebook – and keep doing it while you are asleep.

Automated and Semi-Automated Fact-Checking

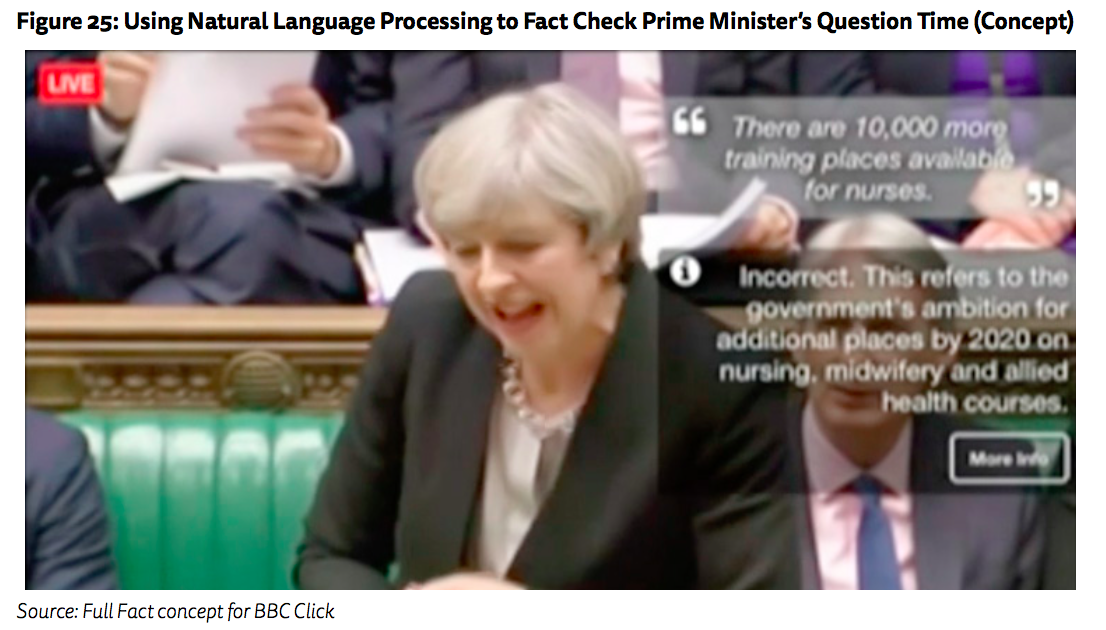

AI can also help journalists fact-check political claims in real time – possibly even while conducting a live radio or TV interview. Speech to text robofact-checkers will allow journalists to ask questions such as ‘is GDP rising?’ and get instant answers. Start-up Factmata is deploying Natural Language Processing (NLP) with previously fact-checked databases of political claims to test this kind of service. Full Fact is using similar technology and machine learning to develop two products aimed at helping journalists and fact-checking professionals, with support from Open Society and Omidyar. They are due to be released at the end of 2018.

The first, Live (see picture prototype below), aims to provide subtitles to fact-check television in real time while the second, Trends, monitors repeated claims and determines who’s making them and where they’re being made, allowing fact-checkers to form a better understanding of why a specific claim is being repeated and to better target correction requests. This work is being done with partners in Argentina and South Africa.

Commercial Optimisation

The use of algorithms to recognise patterns in data and make predictions (machine learning) is also being used to drive commercial decisions. This already tells Amazon the sort of books you like based on previous purchases. Applying this to news, AI driven paywalls will be able to identify likely subscribers and based on previous behaviour serve up the offer (and wording) most likely to persuade them to subscribe. Another use will be to create more personalised advertisements or push e-commerce recommendations based on previous interest shown in particular brands or types of responses.

Intelligent Automation of Workflows

In our publisher survey, 91% of respondents cited production efficiency as a very or quite important priority this year. News organisations know they have to do more with less; they have to find ways of making journalists more productive without leading to burn out. Intelligent automation (IA) is one way to square this circle.

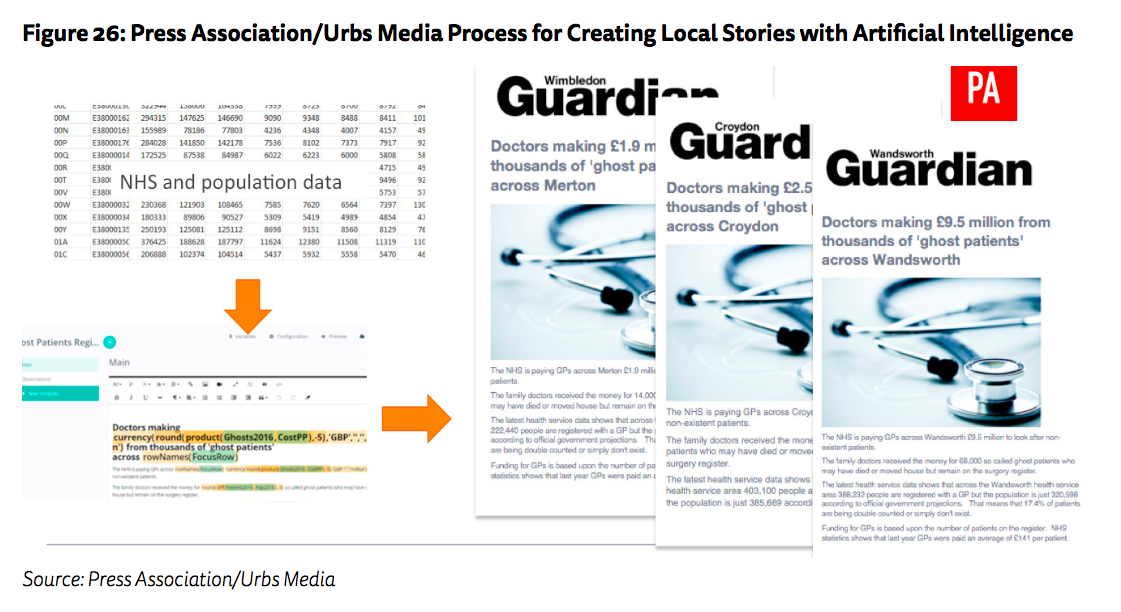

As one example, the Press Association (PA) in the UK has been working with Urbs media to deliver hundreds of semi-automated stories for local newspaper clients. In example below a journalist finds a story using one or more publicly available datasets (NHS and population data). The journalist then writes a generic story that is then versioned automatically by the computer to create multiple bespoke versions for different local publications. Artificial intelligence is used in a relatively simple way to learn and deal with nuances of language such as swapping out ‘in the Isle of Wight’ for ‘on the Isle of Wight’.

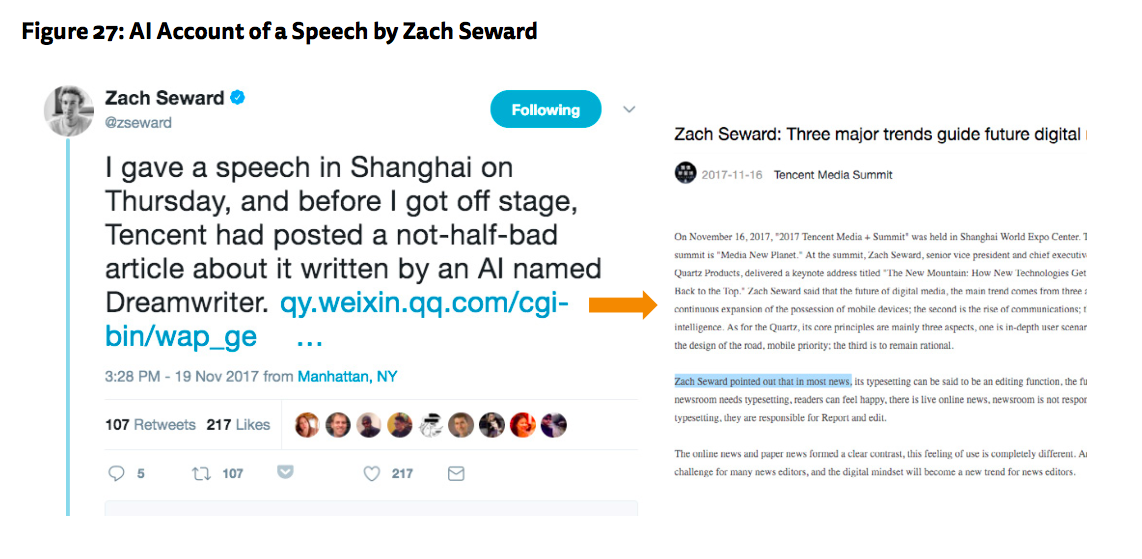

Another potential usage of AI is for reporting of live events. Executive Editor of Quartz, Zach Seward, recently gave a speech in China at a conference organised by tech giant Tencent. This was turned into a news story by a combination of AI based speech to text software, automatic transcription, and an automated newswriting programme called Dreamwriter. Around 2,500 pieces of news on finance, technology, and sports are created by Dreamwriter daily.

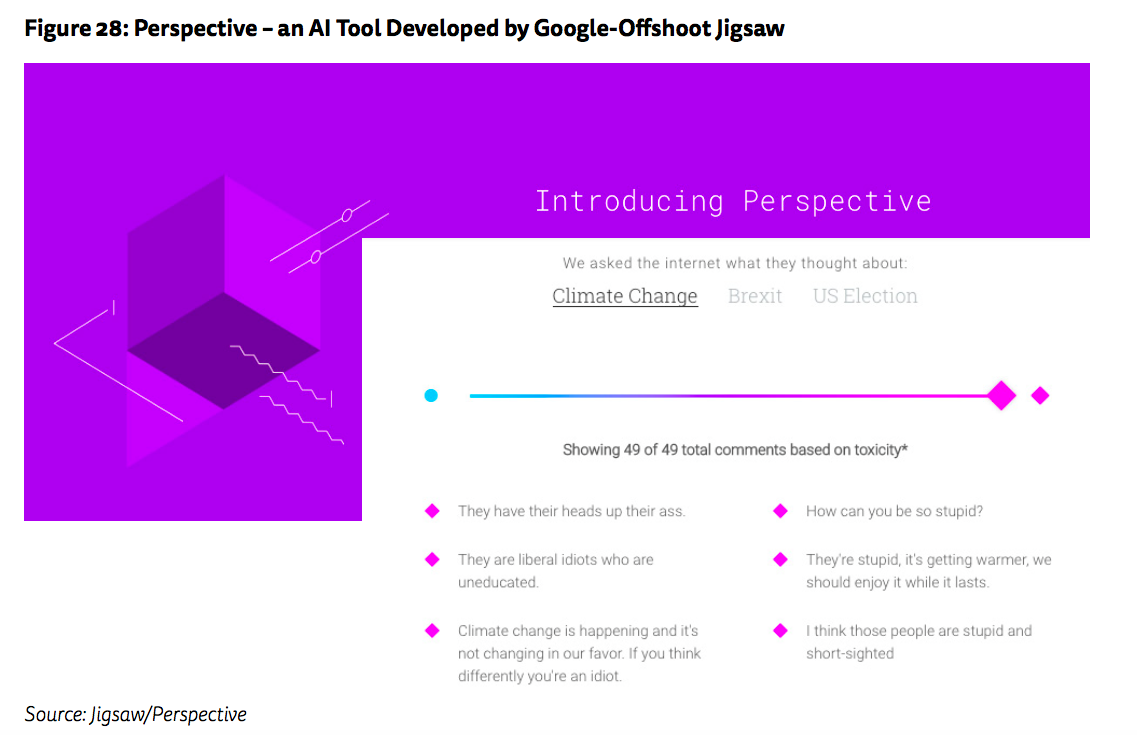

Another early example of intelligent automation is Perspective, an AI powered tool developed by Google-offshoot Jigsaw to help improve moderation of comments. This uses machine-learning models to score the perceived impact a comment might have on a conversation. The first model released was around the ‘toxicity’ of a comment and was based on taking comments from Wikipedia editorial discussions, the New York Times, and other unnamed partners and showing these to real people.

Jigsaw believes that this human inspired collective intelligence will be far more powerful than existing efforts to stop trolls, but critics argue that early results show the dangers of algorithms mirroring existing biases by marking down comments containing words like black and gay.These are early days for AI and freeing the internet from trolls will be one of the hardest nuts to crack. Jigsaw stresses that these systems will only be part of the answer and are designed to help humans do their jobs more efficiently. The New York Times is using the system to increase the percentage of stories with comments from 10% to 80%. But as AI assisted moderation becomes widespread, expect to hear more concerns about censorship and greater calls for transparency.

New Devices and Technologies

Intelligent Speakers and the Battle for the Home

Adoption of voice-enabled smart speakers like the Amazon Echo and Google Home is taking off rapidly, with one report (Juniper Research) suggesting they will be installed in 55% of US households within five years. Globally, the hardware market is estimated to be worth $10.6 billion market by 2022 with Amazon dominating everywhere except for China.

These stand-alone devices are reshaping home ecosystems, with voice becoming an increasingly important way of managing entertainment and controlling smart systems like lights and heating. These systems are taking off in the home first because there is less social stigma than in other locations and because voice is proving a quick and convenient way of managing a range of tasks.

These stand-alone devices are reshaping home ecosystems, with voice becoming an increasingly important way of managing entertainment and controlling smart systems like lights and heating. These systems are taking off in the home first because there is less social stigma than in other locations and because voice is proving a quick and convenient way of managing a range of tasks.

Amazon, which already accounts for around 70% of the market, has the widest range of devices, the most skills/apps (15,000+), and the greatest number of integrations with other manufacturers through its Alexa speech recognition engine. While other players were focusing on the smartphone, Amazon has been building a powerful position as the lynchpin of the connected home. Amazon sold tens of millions of Echo devices over Christmas while, for example, Apple’s HomePod launch was delayed until early 2018.

This year will see the smart speaker wars hotting up further, with Amazon and Google facing competition from Sonos, Samsung, Apple, Microsoft, and possibly Facebook.

This really matters because many see AI-powered smart speakers as an increasingly important gateway to the home, not just for media but for commerce and communication too. In Asia, Alibaba, Xiaomi, Kakao, LG, and Naver are just some of the players looking to get a foot in the door.

Behaviour Changing

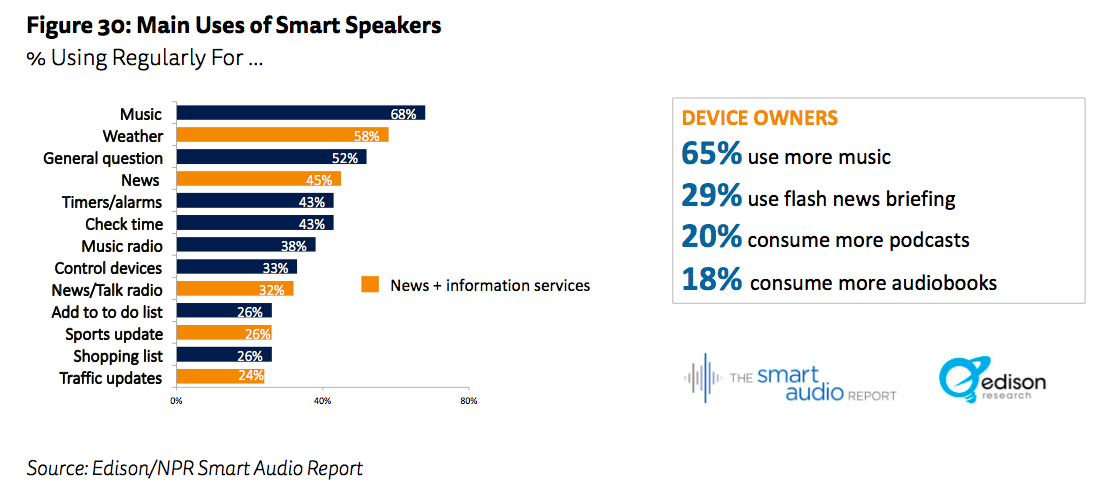

These devices are already changing consumer behaviour, with media content a main beneficiary. The Smart Audio report from Edison Research showed that 65% of device owners listened to more music, with significant increases for news, podcasts, and audio books too. These devices are helping boost revenues for the music industry too, which grew almost 10% in 2017 with streaming subscriptions to services like Spotify up more than 40%.

Voice capable AI assistants are also expanding across other devices, notably in cars and on smartphones and PCs where ultimately assistants like Alexa, Siri, Google Assistant, Viv, and Microsoft’s Cortana, will lead to the greatest level of usage.

All of this will increase the disruption of radio schedules and stimulate more on-demand audio usage. Responding to these trends, media companies polled in our leaders survey said they’d be investing more this year in audio-based media such as podcasts (58%) and shorter form content experiments (58%) that are native to the new platforms. These initiatives were considered more important for publishers than longer form video (47%) and more than twice as important as virtual reality (25%).

Many of us continue to underestimate the acceleration of voice use in the home and on mobile. Some of these devices will have screens but it marks a clear departure from dense text as a way to convey information.

Bede McCarthy, Director of Product, Financial Times

Developments to Watch in 2018

Amazon Forges Ahead with Voice Driven Commerce

On Android smartphones, Google say more than 20% of searches are now via voice. Assuming that this trend continues, Google’s core business is in serious danger of being disrupted. As the Stratechery blog has pointed out, Google doesn’t really have a business model for voice, whereas Amazon already has most of the pieces in place.The vast majority of purchases are initiated at home and Alexa links seamlessly to the biggest retail store and delivery network that has ever existed. A simple series of commands will enable products to be ordered, paid for, and delivered in a frictionless and convenient way – furthering Amazon’s objective of being the logistics provider for everyone and everything. It can afford to give away its devices and its technology, undercutting its rivals, because the money is made elsewhere. Once consumer habits are set – and commands learned – Amazon’s position will be hard to shift.

More Screens Attached to Speakers

Speech input is three times faster than typing on a mobile device, but speech output is far less efficient than reading from a screen. Asking ‘What’s on TV?’ is quick, but waiting for a synthesised voice to run through all the options is an ordeal. This is why more smart speakers will come with some kind of visual display in 2018. This will also open up new functionality such as video calling or monitoring smart home cameras – as well as offering opportunities for less intrusive notifications. Amazon will launch its first branded home security cameras that will link to its video enabled speakers this year.

Implications for Content: More Native Experiences

Look out for innovative formats that go beyond using these devices for distribution. The BBC has created an interactive science fiction comedy called the Inspection Chamber where audience members play a part in the story using their own smart speakers. Share the Facts consolidates a range of US-based fact-checkers into a single Alexa service that responds to questions. Expect to see far more voice driven bots that answer questions or interact in new ways this year, not least because tools like Dexter make it simple to turn existing text bots into Alexa skills. More widely, expect technology solutions that make it easier to create experiences on different platforms (e.g. Alexa, Siri, Cortana, etc.). The BBC has created its own cross-platform engine for interactive stories but expect market solutions to emerge in 2018.

Smartphones and Tablets

Global smartphone growth is slowing. Smartphone shipments grew 3% last year, compared with 10% the year before and 28% year the year before that (Mary Meeker). But despite this, our dependence on these devices is growing. The 2017 Reuters Institute Digital News Report showed that, on average across 36 countries, 46% of smartphone users accessed news from bed and 32% in the bathroom or toilet. In countries like the US we have reached the tipping point with smartphones now preferred by as many people as computers for news.

This growing importance matters because these devices are personally addressable in a way the computer never really was, but also because the smaller screen is changing the formats of news and information more generally. Visually led content will become more important as will push notifications and alerts.

More widely, better cameras will enhance our ability to identify ourselves and other people, while improved software will give us more power to create content of our own as well as instantly communicate with others.

The mobile phone will become our ‘eyes and ears’ on the world thanks to major enhancements with image- and voice-recognition software. These technologies are becoming the new battlefield for tech giants, opening up an array of new media experiences and business opportunities.

Ed Roussel, Chief Innovation Officer, Dow Jones & Wall Street Journal

Developments to Watch in 2018

Camera Driven Search and Discovery

We’ll be doing less typing on our phones this year as visual discovery becomes more important. Google Lens enables your smartphone camera to understand more about objects and then act on that information. For example it can provide information on a building or landmark, show customer ratings for a restaurant, look up product information using a bar code, or turn a business card into text. Snapchat is also using object recognition to identify what’s in users’ photos and then automatically suggest relevant filters. Snap is also looking to commercialise this by linking specific objects or locations to commercial opportunities (i.e. themed filters that could be sponsored by a coffee company or travel company).

Google Lens is already integrated into Pixel cameras and other manufacturers such as Samsung and Apple are working on similar functionality to integrate into phones and software this year.

Foldable Phones Another Nail in Coffin for Tablets

Samsung is expected to unveil a foldable smartphone that will extend the screen to more than seven inches at the Consumer Electronic Show in Las Vegas in early 2018. The technology has been under development for many years and combines portability with a much larger screen when required. The new device, possibly called the Samsung X, will be released slowly, in just a few markets, to test consumer interest. The first models are likely to be prohibitively expensive but over the next decade fold-out screens are likely to become standard not just on smartphones but on a range of other devices too.

Dealing with Lockscreen Congestion

Our lockscreens are increasingly becoming cluttered with a range of messages and push notifications from our favourite apps. This is leading to many consumers deleting apps that send too many messages. In the news space, media companies now compete with aggregators like Apple News and Google News that are also sending more alerts based on previous reading history and other signals.

A recent Tow Center/Guardian Mobile Lab report on notifications showed that some news organisations sent more than 10 alerts per day. Alerts are increasingly being crafted to tell stories on the lockscreen itself and many publishers have branched out beyond breaking news. Only just over half (57%) of alerts studied were about breaking news subjects, with that figure falling to around a quarter (25%) of those sent by Apple News. In 2018 expect to see moves to reduce duplication and increasing the relevance of alerts. Expect platform companies to add functionality in notification centres to filter the messages that appear by default on the lockscreen – meaning controversially that not everything that is sent will necessarily get through.

Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR)

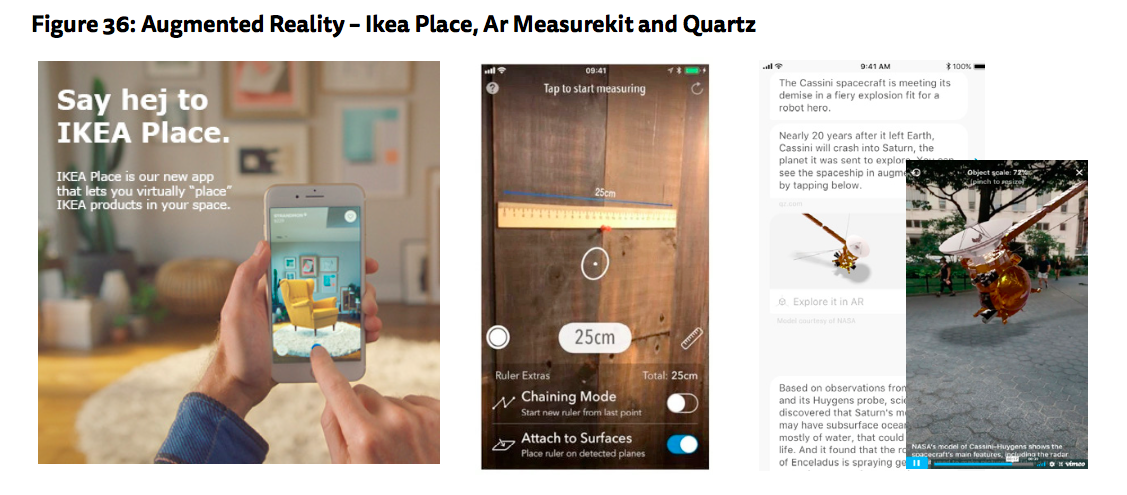

AR will take a major step toward widespread adoption in 2018 leaving VR to focus on building niches in the corporate sector and through games. The key stimulus was the release of Apple’s ARKit and Google’s ARCore, which allows developers to more easily build immersive AR applications that can reach hundreds of millions of existing iOS (iPhone 6S and above) and Android users (more advanced models).

In terms of third-party apps, IKEA Place allows consumers to visualise how furniture will look in their own homes by dropping 3D representations as visual overlays on the smartphone camera. Other early implementations include an app that allows you to measure distances using your phone (AR MeasureKit). Quartz was quick to demonstrate the possibilities for news by incorporating a 3D representation of the Cassini spacecraft as part of its conversational app.

Many of these implementations are still a little clunky but will improve as the year goes on, shaking off, to some extent, the reputation for novelty that came with Pokémon Go and Snapchat Filters. Indeed, for hardware manufactures like Apple, it is essential that AR grows up and starts attracting an older and richer demographic. Smartphone replacement lifecycles have slipped to around three years and AR could provide the next big reason to upgrade.

Key Developments

AR and Mixed Reality Glasses

AR glasses will be back in the public eye this year with the much-hyped Magic Leap headset finally emerging. The Magic Leap One Creator Edition includes smart glasses (Lightwear) with six cameras and an array of sensors on the front connected to a battery and computing pack (Lightpack) designed to ‘produce lifelike digital objects that co-exist in the real world’, according to the company website. This helps our brain process them more naturally, ‘making it comfortable to use for long periods of time’.

Like Google Glass and Microsoft’s Hololens, the goggles will start with a limited release aimed at developers in early 2018. All three products continue to be held back by the challenge of packing enough computing and battery power into a shape – and price point – that works for consumers. Most tech companies are taking the long view on AR glasses. ‘They aren’t here yet, but when they arrive they’re going to be the great transformational technologies of the next 50 years’, said Oculus’s chief scientist Michael Abrash at the recent Facebook F8 conference.

Mixed and Virtual Reality Focus on Corporate Market

For the next few years, we are likely to see a growing split between mobile AR (and mobile VR) delivered to consumers and more expensive and immersive products aimed at the corporate world. Google Glass reinvented itself last year with the launch of an enterprise edition through selected partners. Companies that have adopted the glasses like General Electric (GE) say they have found uses in training staff. Instructions for complex processes can be integrated just above the natural line of sight, making workflows more efficient. Healthcare professionals are also using Glass to record patient visits or livestream consultations.

VR headsets are also being used in training delivery drivers at UPS and at Walmart where in-store simulations help staff to prepare for the Black Friday rush. Direct to consumer VR experiences, on the other hand, remain constrained by the limited number of headsets sold, the fragmented nature of the market, and the lack of quality content.

This year the platforms will be looking to stimulate both the supply of content and the demand for it in key areas. Sport is a natural fit given VR’s ability to immerse audiences in another world and the NBA has been broadcasting games in VR for the 2017–18 season through its League Pass VR. Google Daydream and Samsung Gear headset owners get to see the action for free and we are likely to see similar arrangements for the Winter Olympics and World Cup. In news, both Google and Facebook will be subsidising publishers like the New York Times and the Guardian to step up production of quality content.

Facebook still has big plans for VR that don’t just depend on professional content. Its vision is to engage more than a billion people with the technology directly – through getting users to create their own VR content. Facebook Spaces was launched in April as a virtual meeting and hangout space and after disappointing sales for the Oculus Rift, it has launched a new (cheaper) mass market model (Oculus Go, $199) to stimulate demand. To boost usage it is also opening up spaces to other headset makers, starting with the HTC Vive.

To sum up, 2018 looks set to be a breakthrough year for mobile AR alongside incremental progress with VR. Both technologies will struggle to reach their full potential until portability can be combined with compelling use cases and a sufficiently low price. That is still some way off.

Hearables – Four to Watch

The year ahead will see further advances in technologies designed to bring a range of smart technologies closer to our ears

Amazon Glasses with Bone-Conducting Audio

This may be the surprise launch of the year – without AR but with an embedded Alexa assistant that links wirelessly to a smartphone. A new bone-conducting audio system will allow Alexa to be heard as clear as a bell without the need for headphones.

Pilot for Real-Time Translation

These much hyped ear buds (‘a gadget out of science fiction’) from New York start-up Waverly Labs should hit the market in 2018 after raising a total of $4.5 million in crowd-funding. They offer instant audio translations offline or online, starting with a handful of European languages.

Sony Xperia Ear Open

Currently just a concept but the tech sits behind your ears with two spatial acoustic conductors and drivers that transmit sound to your ear canal. The idea is to allow users to mix real-world sounds with music or instructions from your virtual assistant. This is good for running, city walking, and other situations where you need to be aware of the world around you.

Jabra Elite Sport

These buds are designed for people who like to multitask while taking exercise. They offer fitness tracking, real time ‘in ear’ coaching, and heart rate sensing. Tap the buds to allow audio pass-through so you can pay more attention to the world around you. The gadget also allows easy switching between calls and music.

The Rise of Asian Tech

With technology having saturated Western markets much of the opportunity for growth is shifting to markets like China and India. But Silicon Valley giants like Google and Facebook face restrictions in China in particular, leaving Asian tech firms driving new ideas at a relentless pace. Without a computer-based legacy to worry about, this is a part of the world that is able to fully embrace mobile first technologies. Increasingly we’ll be looking to the East for innovations in technology in 2018.

Mobile Payment Opens Way to Cashless Society

It is becoming harder to pay for goods and services by cash in China, with mobile payment doubling in the last year to around $5trillion, according to analysis by Hillhouse Capital. Much of the growth has come from payment via smartphones within the popular WeChat messaging app. Consumers pay in seconds by scanning bar codes, with roadside stalls accepting mobile payment. WeChat has over 500m users for mobile payment, splitting the market with AliPay, the other big player. Korea is another market where the two big mobile portals (Naver and Kakao) dominate. Kakao Pay is used by around 10m users and comes as part of a package with the country’s most popular messaging app (Kakao Talk). It competes with a growing number of other electronic systems such as T-Pay and Samsung Pay.

Mobile payment linked to powerful e-commerce sites has enabled China’s tech giants Tencent and Alibaba to race up the table of the world’s most valuable companies, becoming genuine long-term rivals to Google, Facebook, and Amazon.

Micropayments Enable New Services

For merchants, the transaction fees with mobile payment cost much less than with a traditional credit card and this is unlocking new business models – including sharing services ranging from bikes to news.

The streets of China’s main cities have become clogged with colourful bikes for rent. For just 15 cents, users can hire bicycles and leave them wherever they want. Mobike and Ofo are two of the largest private bike-sharing operators and both have plans to expand internationally. The upfront fees may be small, but the companies see the data being collected about users as providing a path to future profitability.

Some Chinese mobile news sites have introduced small per article payments for journalists/ authors and the same process applies to livestreaming of content.

AI Driven Apps, from News to Music

Frederic Filloux, author of the Monday Note, has been paying close attention to Toutiao, an app that uses artificial intelligence to aggregate content from around 4,000 traditional news providers as well as bloggers and other personal content. Toutiao has around 120m daily active users and an engagement time of 74 minutes per day. Newsfeeds are constantly updated based on what its machines have learnt about reading preferences, time spent on an article, and location. Toutiao claims to have a user figured out within 24 hours. In Korea, Naver is also looking to add AI recommendations to its mobile services. Line is another mobile news aggregator that is popular in Korea, Taiwan, and Japan. News aggregators like Flipboard and Laserlike have made little progress in the US and Europe. But that could change as Toutiao, leaning on its $22 billion valuation, is looking to move aggressively into the Western countries this year. Toutiao’s parent company Bytedance also recently bought Musical.ly, a lip synching platform popular with American teens that was developed in Shanghai – and one of the first Chinese built apps to become popular in the West.

Indian Mobile Explosion and Smartphone IDs