Executive Summary

In this report, we analyse the potential for collaborative journalism initiatives to address the challenges facing local news. Although collaboration has been examined in the context of national and international partnerships, often among larger news organisations, few studies investigate these efforts at the local level, particularly in Europe. As local media around the world continue to face declining revenues and shrinking newsroom staffs, collaborative approaches may offer a vehicle for producing high-quality accountability journalism at the local level.

This report is based on more than 30 interviews with key figures in high-profile collaborative journalism experiments in three different countries, including journalists as well as senior management, community organisers, data analysts, technical experts, and others. The three primary cases featured are the Bureau Local (UK), ‘L’Italia Delle Slot’ (Italy), and Lännen Media (Finland). We also interviewed the director of CORRECTIV.Lokal, an initiative in Germany seeking to replicate the work of the Bureau Local.

These cases reflect three distinct models of collaboration: (1) a permanent network of journalists and non-journalists engaged in topic-driven reporting projects (the Bureau Local); (2) legacy and start-up news organisations working together on a single extended investigation (‘L’Italia Delle Slot’); and (3) regional news organisations sharing content through a collaborative newsroom (Lännen Media).

These initiatives involve both similar and divergent approaches to network building, project development, and content distribution. Two of the collaborations focus on publishing high-impact stories simultaneously across multiple outlets; the Bureau Local pursues multiple projects each year, while ‘L’Italia Delle Slot’ is a time-limited project focused on one subject. The third collaboration, Lännen Media, includes journalists working in newsrooms around Finland to produce national and international reporting shared among 12 member newspapers.

We find that these very different initiatives feature many common elements that offer potential lessons for other local newsrooms:

- Each collaboration is designed to facilitate concrete forms of resource sharing – of both human and technical resources – while minimising potential competitive friction among the individuals and organisations involved.

- All three collaborations feature diverse and dispersed networks, and are dedicated to creating connections, both virtually and in person, to allow for knowledge-sharing, skills enhancement, and mentorship. They also aim to engage participants as equal partners in editorial processes.

- Participants suggest that collaborative approaches have allowed them to report on topics they would not typically cover as well as engage with familiar subjects in more comprehensive ways. Many said they have also learned how to better incorporate data and multimedia elements into their reporting.

- Two of the collaborations embrace strategies that allow them to connect with communities to tell their stories. The Bureau Local and ‘L’Italia Delle Slot’ have worked to build partnerships with individuals and organisations affected by the issues they cover, while Lännen Media journalists aim for coverage with broad appeal that doesn’t favour particular localities.

- Despite their short tenures, these efforts have shown evidence of impact on a variety of political, social, and economic issues, due in part to distribution strategies in which national and local content is released simultaneously across an array of platforms.

We also find that these collaborations face distinct challenges. In particular, participants cited the need to develop a shared mission and goals, unite newsrooms with different ownership structures and funding models, teach local journalists how to incorporate data into their reporting, adapt their communication and management structures to reflect the needs of participants, and find ways to chart and measure the implications of their work.

People involved in these initiatives are hesitant to suggest that they offer the definitive solution to the problems facing local news, and they do not aim to replace the news industry in the cities and towns where they operate. They also expressed uncertainty about the sustainability of their efforts. Nevertheless, these projects highlight the potential of collaboration for making the most of limited resources, and show the willingness of journalists and other community-level actors to embrace experimental approaches fostering journalism that makes a difference in people’s lives.

1. Introduction

Over the last decade, news organisations have increasingly experimented with collaborative approaches as a way to extend their resources and maximise the reach and influence of their reporting. This trend has been driven by several factors, ranging from economic challenges to access to large data sets and the need to work across borders to investigate global or regional issues (Sambrook 2017). The most visible examples are international projects uniting hundreds of journalists and dozens of news organisations, such as the Panama Papers, which depended on a remarkable culture of mutual trust (McGregor et al. 2017) and has prompted official action in scores of countries around the world (Graves & Shabbir 2019).

Notable collaborations have also emerged between national and local organisations, such as ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in the US, and among local news outlets, such as Resolve Philadelphia’s partnership between newspapers, radio, TV, digital-born outlets, and others (Knight Foundation 2018; Kramer 2017). However, despite signs that collaboration can yield ‘exponential benefits’ at the local level (Stonbely 2017), these efforts have received less attention than high-profile national and international collaborations – and are particularly under-studied in the European context.

This report uses a strategic sample of three case studies in three European countries to examine the benefits, challenges, and potential of collaborative approaches for producing high-quality local journalism. We define collaboration as initiatives or projects through which journalists from different news organisations work with one another and with other actors – such as technologists, data scientists, academics, and community members – to report, produce, and distribute news. We chose cases led by editors and journalists, rather than citizens or other non-journalists, and that were designed specifically to address challenges facing local journalism in the countries where they emerged. We also focused on collaborations incorporating both print and digital distribution strategies.

The research is based on 31 interviews conducted between December 2018 and February 2019 with directors, editors-in-chief, managing editors, newsroom and freelance reporters, community organisers, data analysts, funders, and start-up founders working with collaborations. The cases included in the report are the Bureau Local in the UK, ‘L’Italia Delle Slot’ in Italy, and Lännen Media in Finland. We also interviewed the director of CORRECTIV.Lokal, an initiative in Germany seeking to replicate the work of the Bureau Local.

Context

Local news has been especially hard hit by the economic crisis in journalism. In many countries, once-dominant local newspapers face a structural transformation as their print products decline and digital revenues fail to make up for the losses (Nielsen 2015). Additionally, management strategies focused on cutting costs and maximising profits for local newspapers have raised concerns over declining quality, a lack of critical or investigative journalism, and a loss of connection with local communities (Franklin 2006). Local media also tend to have fewer resources to invest in new digital strategies for content, audience engagement, and commercial efforts than their national and international counterparts (Ali et al. 2018; Hess and Waller 2017; Jenkins and Nielsen 2018).

Meanwhile, collaboration across newsrooms has become an increasingly common alternative for resource-challenged news outlets. A report by the Center for Cooperative Media, chronicling 44 collaborative projects mostly in the US, found that these initiatives vary in their level of integration, commitment, and duration, but they all seek to ‘produce content that is greater than what any individual journalist, newsroom, or organisation could produce on its own’ (Stonbely 2017, 14). Participants in US-based collaborative efforts have cited other benefits, including fostering ethnic, gender, and geographic diversity; gaining expertise to cover complex stories; expanding the reach of content; offering access to topics, geographic areas, and sources not ordinarily covered; providing collective leverage; and spurring public discussions about key issues (Bryant 2017).

At the local level, editors, reporters, and others associated with small-market newspapers in the US have suggested that coalitions, associations, and partnerships are increasingly important, such as for negotiating with digital platforms, including Google and Facebook, and sharing risks and responsibilities across outlets (Ali et al. 2018). Hess and Waller (2017) contrast collaborative approaches with the centralisation and dispersion of local content production that has occurred across much of the local media ecosystem; rather, a collective strategy ‘moves the emphasis from profit to preservation’ (p. 197).

Collaborations often revolve around data-driven reporting, helping transfer a highly valued and still largely specialised skill from larger, mainly urban newsrooms to local and hyperlocal journalists (Ausserhofer et al. 2017; Stalph and Borges-Rey 2018). These initiatives also connect local journalists with data experts (analysts, developers, graphic designers, academics) as well as specialists in other topic areas (NGOs, activists, community members).

Although potential advantages of collaboration are well-documented, little research exists about the ways that local news organisations have experimented with collaborative journalism, or about the particular challenges they face and the approaches they use to build and manage collaborations that unite participants with differing backgrounds, experience, and expertise.

Research Approach

To begin to answer these questions, this report offers a close examination of three case studies representing very distinct models of collaboration: (1) collaboration among a network of journalists and non-journalists engaging in topic-driven reporting projects (the Bureau Local);

(2) collaboration among legacy and start-up news organisations on a single topic (‘L’Italia Delle Slot’); and (3) collaboration among regional news organisations through shared content distribution (Lännen Media).

We chose these initiatives to reflect the wider diversity of collaborative efforts in Europe; each addresses different challenges and involves different types of professional groups and organisations. The cases also represent multiple media systems (Hallin and Mancini 2004) encompassing very different media markets (see Table 1) and landscapes for local news. For example, while national media companies and brands dominate the UK news environment (Nielsen 2015), Finland is distinguished by regional titles and high levels of ownership concentration (Hujanen 2008) and Italy’s newspaper market is led by two primary publishing groups owning national and local titles (Newman et al. 2018).

Table 1. Media markets for countries covered

|

Finland |

Italy |

UK |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Population (millions) |

5.54 |

59.3 |

66.6 |

|

Internet penetration |

94.3% |

92.4% |

94.7% |

|

Media use (2018) |

|||

|

Printed newspapers as a main source of news |

11% (212/1979) |

6% (112/2006) |

9% (188/2035) |

|

Websites/apps of newspapers as a main source of news |

26% (506/1979) |

11% (217/2006) |

13% (267/2035) |

|

Social media as a main source of news |

8% (158/1979) |

10% (191/2006) |

10% (212/2035) |

|

Advertising expenditures (€) |

|||

|

Total advertising expenditures |

1,171.3 |

7,308.9 |

20,376.1 |

|

Advertising expenditure per capita |

211.4 |

123.3 |

305.95 |

|

Advertising expenditures per medium (€) |

|||

|

Newspapers |

362 |

551.3 |

1384.8 |

|

Internet |

370 |

2,138.6 |

12,090.7 |

|

Change in advertising expenditures |

|||

|

Change in internet advertising (2013–17) |

+55.7% |

+34.8% |

+68.3% |

|

Change in newspaper advertising (2013–17) |

-25.2% |

-28.5% |

-40.8% |

Source: Adapted from Cornia et al. (2016: 13). Data: Internet World Stats (2019) for population (2018 estimate) and internet penetration in Dec. 2017, www.internetworldstats.com; Newman et al. (2018) and additional analysis on the basis of data from digitalnewsreport.org for printed newspaper use, websites/apps of newspapers use, and social media use (Q4. You say you’ve used these sources of news in the last week, which would you say is your MAIN source of news?); WAN-IFRA (2018) for size of the 2017 national advertising market (total advertising expenditure in € millions, exchange rates £1/€1.13, 31 Dec. 2017), distribution of that expenditure across media, and changes in internet and newspaper advertising expenditures 2013–17, www.wptdatabase.org/.

We interviewed representatives from multiple levels of the collaborations, including those in leadership positions, those involved with the funding and community-development aspects of the projects, and members of the reporting teams and networks. Interview questions addressed the benefits and challenges of collaboration for local media, how the collaborative project was developed, editorial processes, the nature of the content produced, how audiences receive the content, commercial strategies, how participants see the impact and future of their initiatives, and how the collaborations address deficits in local news in each of the countries.

The 31 interviews conducted for this research took place in person (13) or remotely by phone or Skype (18). (See the complete list of interviewees at the end of the report ; one interviewee wished to remain anonymous.) The interviews were all conducted in English. The interview data were triangulated by analysing news output produced through the collaborations, including articles, data visualisations, interactive features, videos, and other multimedia content. We also examined tools used to connect participants, such as Slack channels and social media accounts, and organisational documents, including website content, press releases, and public presentations.

This report is structured as follows. First, we assess the background and development of each of the collaborative models, including how they define ‘collaboration’ and the challenges in the local-news environments that gave rise to their initiatives. We then examine the structure and editorial routines at work in the collaborations, including their approaches to building their networks and developing and distributing their editorial work. Next, we consider how participants in the collaborations view their relationships with the communities they cover and their perceived impact. Finally, we examine the benefits and challenges they have faced and how these considerations compare across countries.

2. Three Models for Collaboration

Various kinds of formal and informal collaboration have long been present in journalism, from wire services to pool reporting. However, economic challenges and technological change have led many news organisations, particularly smaller, more specialised ones, to openly embrace the potential of collaboration for enhancing the impact and emphasising the value of their work (Graves and Konieczna 2015).

Collaborative initiatives share some key characteristics, such as an emphasis on maximising resources, sharing expertise, producing high-quality content, and enhancing the reach of the reporting, but they also differ in important ways, particularly in terms of the types of actors and outlets participating, the editorial mission or focus of the content, the planned longevity of the project or initiative, and the level of integration of the outlets involved (Stonbely 2017).

This chapter begins by focusing on how respondents working with our three case examples defined collaboration in the context of their own projects. The second part describes the origins and development of each of the collaborative initiatives.

Table 2. Collaborations covered

|

Collaboration |

Country |

Founded |

Participants |

Content approach |

Funding model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

UK |

2017 |

Staff of 6 (director, 2 community organisers, 3 investigative journalists); reporting network of 966 journalists, data analysts, designers, academics, citizens, and others |

Data-driven investigations typically developed by the central staff and shared with a network; projects usually include a national article published on the Bureau Local website and content produced by national and local partners; 10 investigations and 350 local stories published as of April 2019 |

Funded by grants from Google News Initiative (first funder; $660,000, two-year grant), Open Society Foundations (local reporting fund grants awarded to network members), Lankelly Chase, and European Journalism Centre’s Engaged Journalism Fund |

|

|

Italy |

2017 |

Partnership between two data journalism start-ups (Dataninja and Effecinque) and newspaper chain the GEDI Group (publisher of La Repubblica) |

Two data-driven investigations into the prevalence of slot machines and other forms of gambling in Italy, consisting of an interactive online presentation and reporting from local newspapers |

Contract-based payments made by the GEDI Group; newspapers rely on memberships, advertising, and a mix between a freemium and metered paywall model online |

|

|

Finland |

2014 |

12 regional newspapers from 8 parent companies; almost 40 reporters working across the 12 newsrooms, including a team of 10 based in a joint Helsinki newsroom |

Joint news agency of a rotating slate of journalists producing national and international news, background articles, weekend features, theme pages, and commentary and analysis for print and online distribution |

Reporters paid by newspapers where they are based. Member newspapers rely on subscriptions, advertising, and mixed online paywall models |

Sources: Interviewees; Bureau Local website, www.thebureauinvestigates.com/local

Defining Collaboration

Important similarities and differences among the cases were evident in the ways respondents defined ‘collaboration’. They identified common attributes, including sharing resources, identifying reciprocal benefits, drawing together diverse participants, using a common method, and developing and agreeing upon a shared mission and goals.

The first and most important theme respondents emphasised was the value of collaboration for local news organisations, which already tend to have fewer resources to invest in producing high-quality journalism in the digital environment than national and international organisations.

For example, Kyösti Karvonen, Editor-in-Chief of Kaleva, a regional newspaper based in Oulu, Finland, that is part of Lännen Media, said the continuing economic challenges affecting local newspapers in Finland meant regional newspapers needed to seek out opportunities to enhance efficiency and reduce costs while not sacrificing the quality of their reporting. As a result, ‘joining forces’, as he described, with other media houses in content areas in which they do not directly compete presented a viable solution.

Emma Pearson, News Editor at the Lancashire Post in the UK and a Bureau Local network member, said collaboration is defined by the ability of news organisations to share resources in pursuit of producing high-quality journalism in response to dramatic cuts and shrinking capacity.

Collaboration really, for me, is about people getting together and pooling the small amount of resources they do have and using it efficiently to do stuff that’s still good.

Second, respondents emphasised that collaboration provides access to new ideas, expertise, skills, and tools that may not exist in their newsrooms.

Raffaele Mastrolonardo, founder of Effecinque, a partner in the ‘L’Italia Delle Slot’ investigation, said collaboration is defined by complex projects requiring different skillsets and perspectives, which should involve different types of journalism organisations.

Right now, the landscape is pretty diversified, meaning there are traditional media, there are freelancers, and there are small organisations like Effecinque. Or there are small groups of innovators within traditional media. … So when I think about collaboration in journalistic terms, I think about all these different figures pulling together on a single project.

Natalie Bloomer, a freelance journalist based in Northampton in the UK who has worked on multiple Bureau Local investigations, said collaboration allows news organisations to share information, such as data, sources, and other advice to aid reporting.

We’re looking into the same issues already, so it makes sense to join forces and share the information that we’ve each found. Sometimes it can be an issue of resources, so one organisation might have greater resources to look into a particular area and another might have some other skill or knowledge that can bring something else to the article. The key thing is the sharing of information, really.

Megan Lucero, Director of the Bureau Local, sees collaboration as an important community-led reporting tool. The Bureau Local welcomes those with diverse backgrounds and abilities to come together to tell stories – on a variety of predetermined themes – that might otherwise go unreported.

We bring people together who represent different locations, different skillsets, different knowledge, different expertise, with the common goal of investigating stories that are of interest. Telling stories that matter to communities, digging into things that aren’t being told, holding local and national power to account, solving problems that journalists need to face. That’s why our community comes together and collaborates.

Third, collaboration is defined by the editorial practices, processes, and philosophies of the participants, who share similar understandings of how they should approach their reporting and the impact they hope it will have. Like Lucero’s ‘common goal’, other respondents referred to their collaborations as having a ‘shared outcome’ or ‘mutually agreed end’.

For Kathryn Geels, Director of the European Journalism Centre’s Engaged Journalism Accelerator, a Bureau Local funder, collaboration can include news organisations working with one another, with non-journalists and non-news organisations, and with their communities. She said local news organisations have recognised that, to remain sustainable, they must be willing to take risks and try different strategies for reporting, considering a ‘whole ecosystem approach’ rather than emphasising competition. She said this philosophy is evident in initiatives like the BBC’s Local Democracy Reporter1 programme and Google’s Digital News Initiative, in which organisations that could be seen as competitors have become partners.

Considering these responses as a whole, we suggest that local news collaboration can be defined as journalists from different news organisations coming together in a structured way to maximise resources, benefit from the abilities and perspectives of diverse participants, and pursue a common goal, particularly tied to producing high-quality journalism.

Three Approaches to Collaboration

The collaborations in this report seek to address needs specific to their countries as well as those affecting the local-news landscape in general. These collaborations reflect three distinctive approaches (see Table 2) that range from a single-subject investigation to a joint newsroom staffed and funded by different regional newspapers.

Reflecting these approaches, the collaborations are structured differently in terms of their editorial philosophy, management style, distribution strategy, and funding model. In this section, we discuss how each of the collaborations was developed and these key facets of its work.

The Bureau Local

The Bureau Local is a collaborative network, based in London but with members around the UK, that specialises in large-scale, data-driven investigations that can be adapted locally by journalists in different parts of the country. Typically this means producing a large national data set and working with reporters to localise information to their area, by providing reporting guides and other resources to help them cover stories that might otherwise be beyond their reach.

The initiative started in 2017 as a programme of the Bureau for Investigative Journalism (TBIJ), which was founded in 2010 and describes itself as ‘an independent, not-for-profit organisation that holds power to account’, according to its website. TBIJ Editor Rachel Oldroyd recognised that the business model for local news was collapsing, with newspapers around the UK downsizing and in some cases closing, creating the potential for a ‘democratic deficit’ in which many citizens would not have access to the information they need to actively engage in their communities. She sought funding for a potential solution to the decline, eventually securing a €662,000 grant from the Google Digital News Initiative.

Oldroyd recruited Megan Lucero, formerly a data editor at The Times and Sunday Times in London, to serve as the Bureau Local’s director and develop its vision. Lucero and her team visited the US to learn about other organisations focused on collaboration around data journalism, such as ProPublica, and conducted a ‘listening exercise’ through which they visited newsrooms around the UK to gauge local journalists’ interest.

In May 2017, although they had not yet announced their first project, the Bureau Local team was forced into action when Prime Minister Theresa May called for a snap election on 8 June. They launched a series of investigations and, over the next six weeks, created a Slack channel for network members, worked with statisticians to build databases, partnered with universities to hold ‘hack days’ in five different cities, and developed data-reporting toolkits. Lucero said this first reporting experience, which resulted in 150 local articles, set the tone for the investigations to come.

That sort of set the foundation for a lot of things, which is that it showed the power of bringing people together. It showed the power of local ideas and how that can be applied for a national scale. It showed the hunger but lack of information available for people. … The importance of reporting on something before it happens rather than after it happens to empower people to act on it is a really important facet for local [news].

‘L’Italia Delle Slot’

‘L’Italia Delle Slot’ is the title of a two-year investigation into the rise of gambling in Italy, produced by a partnership between two journalism start-ups, Effecinque and Dataninja, and the GEDI Group, which publishes La Repubblica, the country’s largest newspaper, and 13 local newspapers. The two start-ups worked specifically with the Visual Lab, GEDI’s hub for creating visual and interactive digital content.

The inspiration for ‘L’Italia Delle Slot’ came in 2013. Raffaele Mastrolonardo, founder of Effecinque, which focuses on developing innovative approaches to online journalism, said Italy was riddled with slot machines – in bars, tobacco shops, restaurants – and that gambling revenues had been rising since 2004. He set out to find data about the prevalence of slot machines around the country and how they had affected the economy. No data were available, so he filed a request with the government to access relevant public records. The request was denied.

Mastrolonardo then partnered with Alessio Cimarelli, a data scientist and co-founder of Dataninja, a grassroots network focused on data journalism; they discovered that the government maintained an online database of every business in the country, with associated addresses, authorised to house a slot machine. The data set was too large to download manually, so they scraped it. They then compared the numbers with data (shared from Italy’s national research centre) about the prevalence of gambling addiction in different regions of Italy and used population data to determine the number of businesses authorised to house slot machines per resident. This resulted in per-capita rankings of slot-machine prevalence.

Mastrolonardo and Cimarelli wanted to connect with a news organisation to share their findings, eventually partnering with Wired Italia, which created interactive maps and graphics. They also recognised the value their data might hold for local outlets and ran regional analyses of the relationships between the presence of mini casinos (a sub-category of businesses authorised to house more lucrative types of slot machines) and the amount of income people spend on gambling. They approached Il Secolo XIX newspaper in Genoa, which agreed to report on the findings. In 2014, editors from Il Tirreno, the regional newspaper in Tuscany, requested their own version of the investigation.

In 2016, the Freedom of Information Act in Italy was passed. Mastrolonardo and Cimarelli filed another request for the government’s gambling data in 2017 and were successful, receiving records outlining the number of slot machines for the nearly 8,000 municipalities in Italy and how much people spent on them, the first time such data were made available to the public. The pair approached the GEDI Group about collaborating to produce a multimedia news feature. They expressed interest, and Mastrolonardo and Cimarelli determined per-capita slot-machine rates and spending for villages, cities, and municipalities across Italy. They also prepared localised reports to share with the GEDI Group’s local newspapers, and partnered with the University of Pisa to compare slot-machine prevalence with gambling addiction rates among young people.

Marianna Bruschi, who now heads the Visual Lab, said all of the GEDI Group’s local newspapers had covered gambling, but the partnership with Mastrolonardo and Cimarelli offered valuable data and context.

You can write about this game and gambling addiction, but if you don’t have a data set that proves to you, ‘Yes, we have a problem in our city’, it’s not the same. I think that one of the great things about ‘L’Italia Delle Slot’ is that not only did our 13 local newspapers use this project, but in the first week we found on the web almost 50 articles written by very, very small titles that used this data set. So I think this is a great thing.

The first investigation was such a success that the Visual Lab partnered with Mastrolonardo and Cimarelli for a second edition, which was published in December 2018. ‘L’Italia Delle Slot 2’ expanded the data to include not only slot machines but all types of legal gaming around Italy. It also featured additional interactive and multimedia elements as well as another collection of reports from local journalists at GEDI newspapers.

Lännen Media

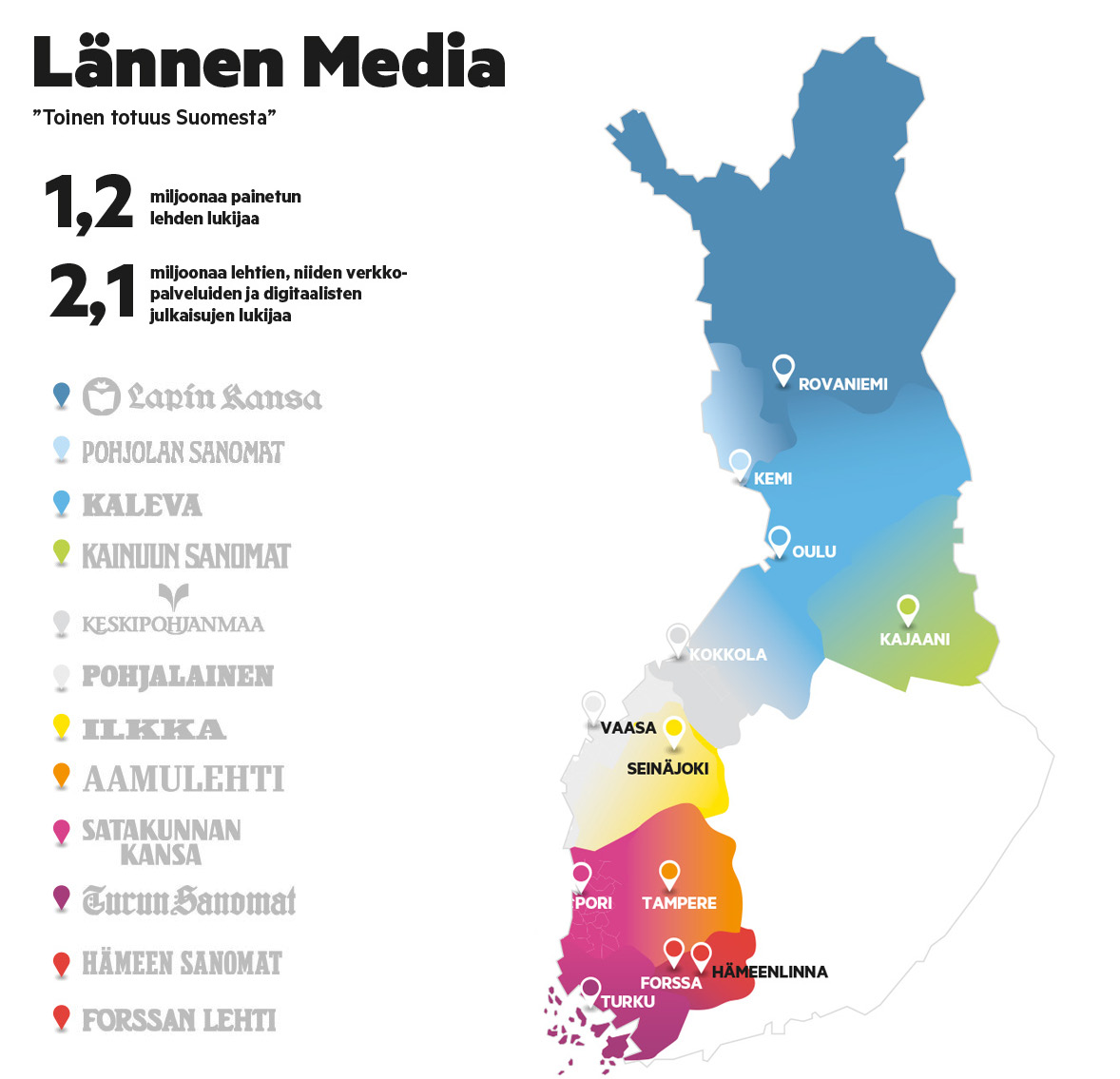

Founded in 2014, Lännen Media is a joint newsroom serving 12 regional newspapers that represent eight different media companies from across western and northern Finland. Lännen Media journalists produce national and international news, background articles on current events, weekend features, theme pages (health, travel, cars, family, etc.), and commentary and analysis for both print and online distribution by any member newspaper.

Collaboration between regional newspapers has a ‘long tradition’ in Finland, said Veijo Hyvönen, Managing Editor of Turun Sanomat in Turku. In 2013, editors with the regional newspapers recognised that sections of their print newspapers and portions of their web content could be produced collaboratively so they could focus on creating local content, said Matti Posio, Lännen Media Editor-in-Chief.

The co-operation was there, but it was kind of messy and kind of random, and then there would always be some sort of quarrel about which region you have to take into account more. We wanted to make something that would serve everybody equally.

The country’s biggest regional newspapers – Kaleva in Oulu, Aamulehti in Tampere, and Turun Sanomat – and some smaller newspapers decided to create a more sustainable option. Kyösti Karvonen, Editor-in-Chief of Kaleva, said the companies faced similar economic challenges, and Lännen Media presented a way to solve their problems.

Those years, we had a downturn and also the media disruption was at full speed, so we had to cut costs, and also, of course, we wanted to improve our content and our journalism for our readers.

Now, with a staff of four editors and and almost 40 journalists working in newsrooms around the country, including a Helsinki-based newsroom of ten journalists, Lännen Media represents one of the country’s largest and most well-developed news-coordination efforts. Participating news organisations disperse costs by paying only the journalists based in their newsrooms, as well as a service fee for Lännen Media content, and the costs are distributed based on the size of the outlet.

Posio said Finland does not have a national newspaper covering the whole country, so regional newspapers serve vital roles, although the rise of digital news is complicating this structure because everyone ‘competes at the same level’. As a result, member newspapers are implementing different types of paywalls, and Lännen Media leaders are working to determine which content readers will pay for across the outlets.

CORRECTIV.Lokal

The Bureau Local inspired a similar initiative based in Germany that works with local journalists on in-depth reporting projects with national significance and local relevance. A project of the non-profit investigative reporting organisation CORRECTIV, CORRECTIV.Lokal aims to share the organisation’s expertise in investigative reporting and data journalism, as well as resources it has developed, such as a crowd-sourcing tool called Crowd Newsroom, for free with local newsrooms. As Director Justus von Daniels described:

We try to offer all these kind of journalistic resources, and that’s why we collaborate with the local level. … We can deliver some resources that they don’t have because they lack the time and sometimes, of course, they lack resources. But what they have, what we don’t have, is the experience on the ground. They are the local reporters. They know the place where they live. They know the people.

Von Daniels said that before launching CORRECTIV.Lokal, he focused on sharing stories his organisation had reported with local newsrooms and asking them to publish the work. He said that, although editors were open to receiving the content, they were concerned that the stories did not reflect their writing style or did not focus on their town.

Instead, CORRECTIV.Lokal allows von Daniels and other CORRECTIV staff to work alongside local newsrooms as partners on large-scale investigations. In February 2018, they began with a series aiming to make housing markets more transparent, beginning with ‘Who Owns Hamburg?’ (see Figure 1) and moving to five other cities around the country.

Working with the daily newspaper Hamburger Abendblatt, they launched a campaign to raise a debate in the city about the housing market, including setting up a ‘mobile office’ to meet with citizens, hosting weekly debates, creating a newsletter, and launching a Crowd Newsroom to collect structured data on ownership and tips from the public. Von Daniels said the initiative reaped other benefits as well.

Figure 1. CORRECTIV.Lokal’s ‘Who Owns Hamburg?’ investigation, published in November 2018

For us, a fairly small organisation, we got visibility in the city which we wouldn’t have ever had, and for a non-profit organisation … it’s key that people get to know you because we actually want to get people to fund us, to support us on an idea level but also on a financial level. So, people in Hamburg could learn or could see what we’re doing, how we’re doing it, they can trust this kind of journalism — that was really good. (Justus von Daniels)

CORRECTIV.Lokal moved from Hamburg to Berlin and Düsseldorf to conduct similar investigations. From these larger partners, they are also launching three new collaborations with local newspapers in smaller cities (80,000–120,000 residents) in spring 2019.

Von Daniels said this focus on training and working with local newsrooms and local citizens serves two purposes. First, it allows journalists to show that ‘Journalism is not magic, and you can help us, you can be part of it.’ Second, local journalists need to remind readers why they should subscribe to their local newspaper and follow its reporting.

I think that’s why this investigative stuff is so important, saying, ‘We really care about the problems that are here; we are trying to hold power accountable in our region.’ … I think you get more trust or people feel more affiliated to journalism if they see that journalists care.

3. How Collaborations Work

The collaborations explored here were formed to address different needs in their countries and to achieve particular editorial aims. Although they all endeavour to produce or enable the production of meaningful local news, they rely on different types of management, editorial, and distribution strategies to develop and share this content with audiences.

Different models for collaboration have been identified in other contexts, such as in the US, where researchers outlined six approaches – temporary and separate, temporary and co-creating, temporary and integrated, ongoing and separate, ongoing and co-creating, and ongoing and integrated (Stonbely 2017). These models suggest different levels of commitment and integration, with an overall desire to create high-quality content.

Other elements are key to ensuring that collaborations operate successfully, including the need to build trust and develop clear structures and guidelines; involve neutral partners in editorial co-ordination, communication, and problem-solving; use technology strategically; establish a clear purpose and metrics for success; and reinforce the value of producing investigative journalism (Sambrook 2017).

In developing their collaborations, the Bureau Local, the ‘L’Italia Delle Slot’ team, and Lännen Media relied on specific strategies. This chapter focuses on the operational practices for the collaborations, including how they recruited partners and built their networks, their approaches to editorial project development, and their methods of content distribution.

Building a Network

The success of the collaborations, according to respondents, depends not only on creating high-quality journalism but also on recruiting dedicated partners with shared goals. The collaborations studied for this report feature networks of varying sizes and include participants ranging from journalists in local newsrooms to freelancers, data scientists, academics, technologists, and founders of news-based start-ups.

The leaders of the collaborations also use different techniques for recruiting, communicating with, managing, and maintaining the individuals involved with their work, who, in all cases, are dispersed around a large geographic area. They rely on both top-down and bottom-up structures, remaining open to refining their processes to adapt to the needs of participants.

The Bureau Local: A Transparent Approach to Organising

The Bureau Local launched in March 2017 with the aim to ‘build a network of regional reporters and tech experts across the country to investigate large-scale datasets and uncover local public interest stories’, according to a blog post on its website. They also aimed to maintain a transparent approach to organising in which methods and strategies could change depending on the needs and interests of the network.

As noted, the Bureau Local embarked on its first project just two months later – a multi-pronged investigation into the UK snap elections, including a look at targeted political advertising (‘dark ads’) on social media, the political power of new voters, the level of reporter access to party leaders, and the use of crowdfunding for political campaigns. To engage interested journalists in the project, the Bureau Local team launched a Slack channel. By the June election, the network had grown to more than 350 local journalists, bloggers, civic tech workers, and others from 84 cities around the country, according to a Bureau Local blog post.

Since the election investigation, the Bureau Local has overseen several other projects, including covering domestic violence provision, racial profiling at immigration checks, homeless deaths, and local council spending pressures. Each investigation is announced to the network via social media, emails, and the Slack channel. Participants receive the tools they need to get involved, including access to data, ‘reporting recipes’ (described as ‘how-to guides for using our data and developing the story’), and code for analysing and visualising data.

The Bureau Local also hosts ‘hack days’ during which network members learn how to gather, organise, and analyse large data sets. The first hack days, which focused on voter power, were held simultaneously in five cities around the UK and featured data from the UK census, Labour Force Surveys, the British Election Study, and past votes and registration numbers (Ciobanu 2017).

Birmingham City University’s Paul Bradshaw helped organise the hack days. He said these events should address topics that have broad implications for society – ‘Let’s shine the light on something good as well as the bad, a problem that needs solving’ – and include a diversity of participants, such as local journalists, developers, open-data advocates, people from the non-profit sector, politicians, and others.

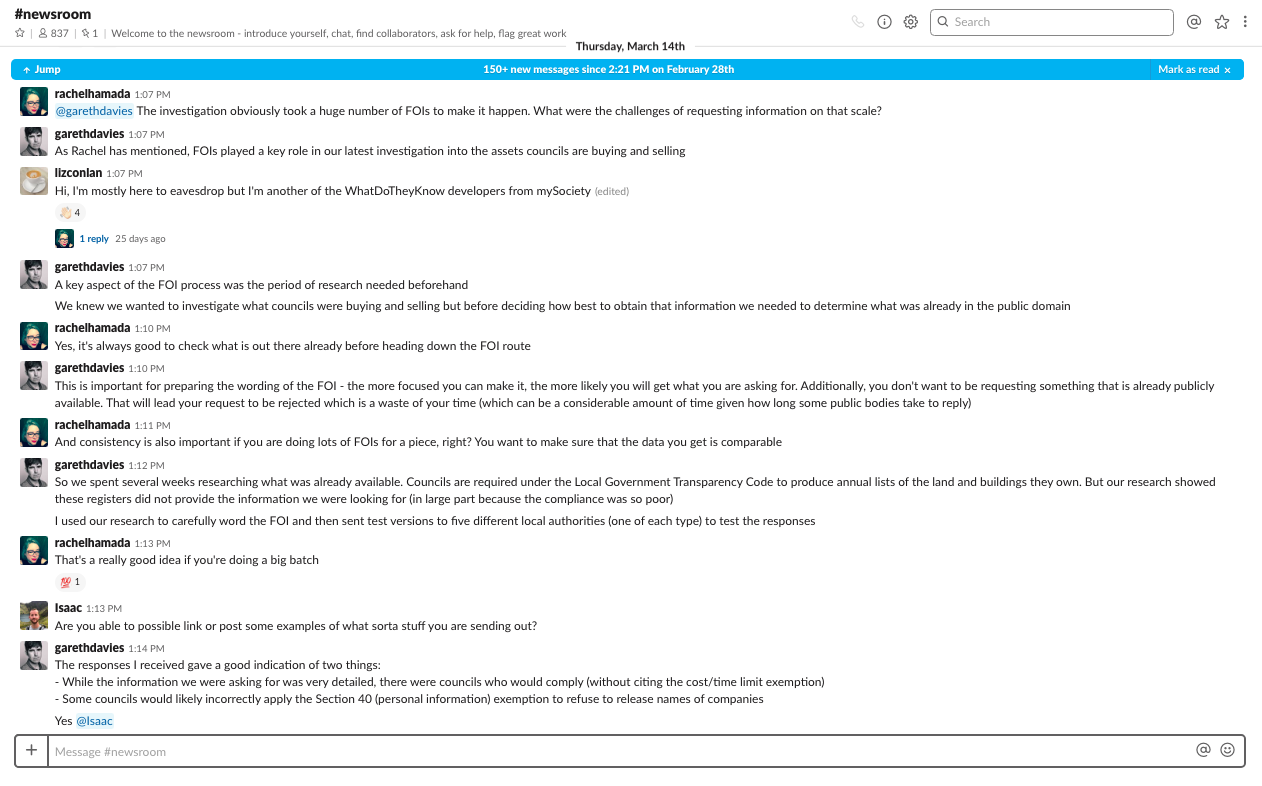

The Bureau Local has also begun hosting one-hour ‘open newsrooms’ on the Slack channel (see Figure 2). Rachel Hamada, one of the Bureau’s community organisers, said the open newsrooms focus on a particular topic but also include opportunities to highlight recent work by network members and ‘do a bit of troubleshooting together’. Open newsrooms have explored how to glean additional information from a postcode or address, challenges associated with court reporting, and how to effectively involve communities in journalistic work.

Figure 2. The 14 March 2019 Bureau Local open newsroom, hosted on Slack, focused on sharing questions and advice about FOI requests, specifically in the context of local council investigations

During the open newsroom focused on postcodes, Bradshaw and Anna Powell-Smith, a developer and data analyst, assisted journalists trying to identify the kinds of properties on a list of addresses sold by local councils. Powell-Smith said the open-newsroom approach differs from her previous work on data-driven projects, in which journalists tended to be more protective and less open about their work.

It’s kind of unusual because the newsrooms I’ve worked with before would find it very difficult to do an approach like that where they FOI’d every council, every local authority, so 350 local authorities, and they got all these data sets back, and I think probably a newspaper was finding that really hard to work with because they’d have 350 different data sets in different data formats, like some are incomplete, some are really messy. So probably a normal newspaper wouldn’t have the capacity to do that kind of project except for maybe The New York Times or something. … The Bureau Local has this unusual newsroom model where they can get local people working on it and spotting stuff.

Although not all network members regularly use the Slack channel, multiple respondents said it offers a useful resource to receive advice about using data, finding and working with sources, acquiring public documents, and other topics. Emma Pearson, News Editor with the Lancashire Post, who has worked on projects such as the domestic violence investigation, said:

It’s been good for sharing ideas, and even stuff that we’ve sort of been talking about, but it hasn’t worked out for various reasons – there is still stuff that you can take away from that. … Practical questions about the Bureau, which they are always very helpful and always very keen on answering, but it’s also quite a good resource for ideas and chatting to other journalists. It’s nice to see outside of your own bubble sometimes.

‘L’Italia Delle Slot’: ‘A Very Collaborative Work Process’

The ‘L’Italia Delle Slot’ project began when Raffaele Mastrolonardo and Alessio Cimarelli approached the GEDI Group’s Visual Lab about co-operating on a project focused on the prevalence of slot machines in regions around Italy. Marianna Bruschi, Head of the Visual Lab, said the partners in the collaboration each had a different role to play, with Dataninja and also Effecinque providing and interpreting the data set, the Visual Lab determining how to visualise the data, and journalists in local newsrooms producing stories with community impact. They also worked with Amministrazione Autonoma dei Monopoli di Stato (Autonomous Administration of the State Monopolies) to provide context for the findings of the data analysis and develop a guide to the laws and games referenced in the project.

To aid the reporting process, which took two to three months, Mastrolonardo and Cimarelli created reports for each local newsroom, including data about their city as well as tables with data on the top 20 cities in their surrounding region and an interactive map. The reports served as a starting point for the local journalists, who could decide how to frame the story and what types of sources to interview, while the Visual Lab assisted with producing videos and other multimedia elements. Mastrolonardo and Cimarelli ensured that the data were presented clearly in online infographics and interactive features.

Mastrolonardo said he and Cimarelli engaged actively throughout the process, even participating in a press conference at the Italian Parliament to share the results with politicians, anti-gambling citizen associations, and representatives from the gambling industry.

It was a very collaborative work process. It was very satisfying. … The fact, for instance, that we were invited to the press conference and we were on the stage for the press conference – I mean, they did consider us as partners. We worked as their partners, not just people who were handling that work. … The original idea is ours, mine and Alessio’s basically, so they recognised that.

Lännen Media: ‘Partnering with our Rivals’

Lännen Media began with three regional newspapers and a few smaller titles, and grew to a network of 12 around the country (see Figure 3). The Lännen Media team includes about 40 reporters working across the 12 newsrooms – all have at least one reporter, with larger organisations housing up to six – including a team of ten working in a newsroom in Helsinki providing national and international news on politics, economics, courts, crime, and sports.

Figure 3. A map of participating newspapers in Lännen Media

Veijo Hyvönen, Managing Editor of Turun Sanomat, a regional newspaper based in Turku, said that because his newspaper and others in the region compete for the same readers, ‘the most promising partners are also our rivals’. So, Lännen Media newspapers have focused on co-operating through sharing national and international news, which results in more resources for them to focus on creating high-quality local and regional content. Hyvönen said:

I think it’s more important with a smaller newspaper because they are afraid that if we start to do too much co-operation that they will somehow lose the battle, so we let them do their work and we do ours.

Editors are also placed around the country and often travel for meetings. Because the Lännen Media reporting network is so widely dispersed, they use video conferences to stay connected. Each morning, Lännen Media’s four editors meet with the 40 reporters to discuss their planned stories for the day. They then meet with editors from the participating newspapers on the same video channel to update them on editorial plans and determine what Lännen Media content the newspapers will use. A content management system also allows Lännen Media editors, reporters, and newspapers to stay connected and follow the progress of current and planned reporting.

The reliance on video conferencing can also present challenges for Lännen Media reporters based in regional newsrooms. Ossi Rajala, a journalist based at Turun Sanomat who covers domestic and international news, said:

The video conference is OK, it works, but it’s not as good as being in the same room. In Helsinki, there are seven journalists there. Then it’s easier to talk about ideas and suggest improvements. Here, all who are sitting around me are working for Turun Sanomat, and I’m the only Lännen Media journalist there, so it’s a bit more difficult because they don’t know what I am doing and I don’t know what they are doing. It’s a bit more lonely to work here than in Helsinki.

Collaborating with journalists working in a range of newsroom environments also means that Lännen Media editors must work to understand and accommodate a range of organisational cultures, journalistic routines, and work styles. Päivi Ojanperä, a features reporter based at the Turun Sanomat, said:

It’s probably how you handle chaos. The methods differ: if you have a lot of material and maybe three stories that you are writing or planning at the same time, it’s not always so easy, but some people may have a very strict plan how to proceed and other people will say, I’ll do this now and maybe a little bit of the other story later today and so on.

Project Development

Each of the collaborations takes a distinctive approach to news production, depending on its structure. Different strategies are applied for areas including topic selection, frequency of publication, reporting methods, presentation style, and level of involvement from editors, reporters, data analysts, designers, and web developers.

The Bureau Local: If it’s Happening Here, is it Happening Elsewhere?

The Bureau Local’s investigations are typically developed by the central team, which shares data, reporting guides, and other resources – including cash grants – so network members can find local stories.

In 2017, for instance, the Bureau Local began a long-term project called ‘Dying Homeless’, which collaborated with local journalists, non-profit organisations, and grassroots groups to record the deaths of homeless individuals in the UK. After conducting an initial count, the central team asked the reporting network to investigate deaths in their areas and add their information to the national database. (They have counted the occurrence of 800 deaths since October 2017.)

Freelance journalists Samir Jeraj and Natalie Bloomer spent four months reporting on homeless deaths in Northampton. They also received a local reporting fund grant from the Bureau Local to assist with their work, which Jeraj said allowed them to spend several days in Northampton (Jeraj is based in London) to interview people living homeless, people working for outreach organisations, shelter employees, and others.

Before they began reporting, Bloomer said, she and Jeraj met with Bureau Local staff to discuss what data and information they had and what they still needed to gather, and they were assigned an editor to answer questions. Bloomer said of working with the editor:

It gave you the support that you would have if you were working for a publication rather than being freelance. So it was the best of both worlds; we had the freedom to look into a story that we really cared about, but we had the support and resources available that you would get from, say, working for a publication.

The reporting ultimately found that homeless people had been turned away from the local night shelter despite it having available spaces. It was published on the Bureau Local website and in the Northampton Chronicle & Echo, as well as being featured on BBC Radio Northampton.

As part of the same investigation, freelance journalist Emily Goddard and photographer Alex Sturrock spent four months reporting on teen homelessness in Milton Keynes, where she lives, which was also funded by a local reporting fund grant. Goddard said the grant was vital to giving her the time to build relationships and trust with her sources.

It was purely time, which is obviously so important, and it’s just very difficult to find it when you’re a freelancer and when you’re doing lots of small jobs that aren’t making a lot of money. You’re kind of always thinking about, ‘Oh, I need to be able to do more to make sure I’m making enough.’ And when I did that [grant], it just gave us the flexibility and freedom to be a lot more flexible.

In other cases, the Bureau Local takes a more ground-up approach. In 2018, the network began a long-term investigation into funding cuts affecting domestic violence refuges around the UK, after investigative journalist Maeve McClenaghan saw a news report about drastic cuts in one community, Sunderland.

We thought, if that’s happening there, is it happening elsewhere across the country? The hypothesis was, this is not a one-off case, we know that council funding is being decimated, is this happening elsewhere?

McClenaghan and Bureau Local intern Jasmine Andersson began talking with refuge managers, who were hesitant to speak publicly. So they created an online survey and invited local journalists to share it with sources in their communities to determine whether funding had been cut, learning that more than 1,000 women and children had been turned away in the previous six months because funds were cut or reallocated. They compiled these data into ‘reporting recipes’ for other network members.

Tom Bristow, Investigations Editor at Archant, a publisher of regional and local media, described the approach of the domestic violence investigation, in contrast to other Bureau Local projects:

That wasn’t a case of, ‘here’s the data, here’s the reporting recipe, have a look and see what you think for your area’. That was more like a, ‘we want to look at this, let’s see what people come back to us with‘. It was more one where we had to go out and get the data ourselves and then we all shared it, shared the interviews. That was more like a collaboration in terms of working on the story together from an early point.

McClenaghan said she was proud of the final result.

What was really gratifying was when these really beautiful, deep, nuanced reports came out across the country. … With something as sensitive as this, obviously you can’t just ring up your local refuge and say, ‘Find me a woman that will cry for me on the radio.’ But they had been talking to people for weeks, if not months, and they had the national context and what was happening in their local area.

‘L’Italia Delle Slot’: Turning Problems into Opportunities

When they were invited to participate in the first ‘L’Italia Delle Slot’ project, some journalists in GEDI’s local newsrooms, particularly smaller ones, were intimidated by using a large data set to investigate the rise of slot machines in Italy, Bruschi said, but working with a central newsroom allayed concerns.

The reaction is very different, because for a small newsroom, it can be a problem, so you have to help them to not consider this as a problem but an opportunity.

Paolo Cagnan, Deputy Editor-in-Chief for four GEDI newspapers in the Veneto region, said that once his newspaper received the data, as well as some infographics and other visualisations, he assigned a reporter to the project who would work with a small team to produce print and online content. The team created a long-form article addressing gambling in Europe, then in Italy, and then in the region, and conducted 20 interviews with people commenting on the findings of the analysis, including citizens, politicians, health providers, and representatives of civic organisations working on the issue.

Figure 4. The homepage for ‘L’Italia Delle Slot 2’, published on the GEDI Digital Lab website in December 2018

Anna Ghezzi, a reporter at La Provincia Pavese in Pavia, said that when she received the data for the first investigation, she found it clean and easy to use, and she worked to determine what stories to follow, focusing initially on the amount of money earned by the state from slot machines in each town, which she accompanied with personal stories from local people who used and owned the machines. She said she also compared the amount of money spent at every machine in her town versus smaller and larger cities.

In summer 2018, Bruschi contacted Mastrolonardo and Cimarelli about creating a second edition of ‘L’Italia Delle Slot’, based on a new Freedom of Information Act request covering all types of gambling (see Figure 4). The data specialists played a similar role in the second edition – cleaning, organising, and interpreting the data – but did not create local reports for the GEDI Group’s newspapers, as they now had the experience to conduct their own analyses. The journalists received a simplified data set with information about their region and top 20 cities, as well as a glossary with definitions for the different games. They had a shorter turn-around – two weeks – than with the first version. As Mastrolonardo described the process:

There were the inputs from us, which were mainly data and analysis, then there was the input from the freelancer who did the design. And then there were the developers and the data people within the lab that were developing the application and the receiver of the reports that were in the local newspapers. The central hub was the Visual Lab.

Lännen Media: ‘A Premium News Agency’

At Lännen Media, story ideas come from the editor-in-chief, news editors, and the journalists based at newsrooms across the country. A primary challenge is identifying stories that will be of interest to readers around Finland, particularly in the areas served by partner newspapers. Editor-in-Chief Matti Posio said that when determining which news Lännen Media should cover, they consider whether the story is interesting and the effect it will have on the lives of readers.

In terms of news, the capital city issues are less dividing than stories from other regions, so when you have a story from another region, the reader would always ask, ‘Why are they having this story from a different region? Are they trying to somehow trick me or just use the same stories again and again in various places? What is this?’ But there is no problem with the Helsinki-based stories in that way. So, from another region, it needs to be a really big news event, like a major car crash or whatever, but what we do is, we try to cover the issues and then we would use the people and interviews and cases from those regions where the journalists are.

Reporter Rajala, who is based at Turun Sanomat, said reporting stories that resonate with all regions in Finland can be challenging and might vary depending on the news event.

It’s a bit tricky, especially about the weather, because the weather in the south and north are completely different [things] in many times of the year. So, at the beginning of the week, we had a big storm in Finland. Of course, in the southern parts they were more affected than in the north, but I wonder if the northern newspapers weren’t so interested, but we did a lot of stories. Sometimes they win, sometimes the southern papers win. But, in general, it should be like that, that the topic considers much of the people, no matter where they live in the country.

The staff of Theme Editor Riikka Happonen are responsible for developing several theme pages each week and three to four features for the weekend, including topics such as lifestyle (work, home, relationships), health, consumer news, food, travel, and cars. She said that because of the longer turn-around time for features, her team, which is housed in multiple newsrooms, spends more time discussing story ideas and sharing feedback with one another.

Our themes are so-called ‘useful information’ for the reader, so it comes from those interpretations, and I think our newspapers are expecting that we are doing those kinds of stories for them. They can do the local entertainment and news by themselves, but we get something more, and I think also we have to think about the reader. Otherwise, our stories are not so important to the reader – the reader may read local news in any case, but there has to be a reason why he is interested in our common stories.

Turun Sanomat’s Hyvönen said editors at participating newspapers can suggest stories to cover, but decisions are ultimately left to Lännen Media staff, although the newspapers’ news editors determine which articles they want to print. In some cases, newspapers use a Lännen Media story for national context while assigning their journalists to provide local context.

Whenever there is a bigger story and it’s one where we can add some real information, then we would do it. For us it’s like a news agency. Like a premium news agency.

Content Distribution

All three of the collaborations aimed to reach as wide an audience as possible. They pursued this goal through empowering a network to concurrently produce multiple local articles focused on one overarching topic (‘L’Italia Delle Slot’, the Bureau Local) or multiple beats or subjects (Lännen Media). Articles were presented in various formats, from local and regional print and online newspapers to national digital-born outlets to radio and TV features to hyperlocal websites and blogs.

In two of the collaborations, the Bureau Local and ‘L’Italia Delle Slot’, this reporting was also accompanied by a centrally developed online portal, which included articles offering national context and links to the local articles, as well as infographics, videos, and interactive features.

The Bureau Local: Creating a ‘Big Push’

The Bureau Local’s investigations, which are published with local and national press partners, are all released on the same day to enhance the impact of the reporting and spark local and national dialogue.

Archant’s Bristow, who has participated in several Bureau Local investigations, said this strategy has been effective and allows more people to see the stories than would otherwise, from local and national politicians to citizens to those directly affected. It can also inspire days or weeks of follow-up reporting.

Rachel Hamada said having one fixed publication date can be a challenge for the Bureau Local team, which needs to ensure that national print or broadcast coverage lines up with the embargoed date that network members sign up to, but the benefits make it all worthwhile.

What it creates is a big push, a big impact. Lots of local politicians will see the stories at the same time, national politicians, and so on. It’s proven to be a really effective formula. People could break the embargo. I’m not sure what we could really do, but people have tended not to, probably because, I think, people see the value in presenting those stories collectively. There’s much more power in them all coming out at once than them coming out in a dribble.

Director Megan Lucero said the centrally produced national report for each investigation, produced by Bureau Local reporters and released on its website, plays an important role in ensuring all the reporting reaches a broad audience.

We always focus on having local stories and national stories because both need to be told. They need to be seen by those who can change it. At the end of the day, we are looking at systemic issues, and it’s important for people to be informed locally and nationally about these findings. These stories have to be put at the seat of power.

‘L’Italia Delle Slot’: An Opportunity for Interactivity

Both editions of the ‘L’Italia Delle Slot’ project were released as a Visual Lab-created website with interactive interfaces so users could access data on their particular cities and regions, as well as infographics and data visualisations, a glossary, and in the case of the second edition, a comparison with the previous year.

These features were accompanied by a collection of articles published simultaneously across the GEDI Group’s 13 local newspapers and the local editions of La Repubblica and La Stampa. All the local newspapers received the date on which the articles should be published within the group, and they could produce follow-up reporting.

The Visual Lab’s Bruschi said this distribution strategy – a centrally produced web presence linking to the local articles – allowed the local newspapers to give their readers access to more complex, customised, and interactive web features than they might otherwise. The project also spurred reporting on slot machines and gaming by non-GEDI newspapers around Italy.

Deputy Editor-in-Chief Cagnan said that, although his newspapers allocated two pages to the first investigation, they continued to follow the topic over the following days, ‘interviewing and trying to understand the reasons why’ slot machine usage and distribution had grown.

Lännen Media: Finding an Online Strategy

For Lännen Media, dozens of stories are made available daily to the partner newspapers via a shared content management system (Lännen Media does not have its own distribution platform). The newspapers then choose the stories they want to publish. In Kaleva, for example, 30–40% of articles a day, on average, are produced by Lännen Media.

Once a story has been assigned to a Lännen Media reporter, whether in Helsinki or one of the partner newsrooms, a photographer and graphic designer from that newsroom (or a Helsinki newsroom or freelance photographer) create visuals to accompany the piece, which can then be shared with other Lännen Media publications. Lännen Media makes print articles and layouts available to newspapers, as well as online versions.

News Editor Jussi Orell said Lännen Media editors now make daily decisions about which articles participating newspapers can publish for free and which offer ‘something extra’ to justify payment, such as a piece of political commentary or a human interest feature on Finnish politicians or ‘interesting common people’ – stories that cross regional boundaries.

I think that in terms of the person we are writing about, it doesn’t matter where he or she comes from. If the story is interesting enough, it works.

Editor-in-Chief Posio said analytics connected with digital content, which are provided by partner newspapers, increasingly inform news selection. Often the most popular stories are those that address ‘what’s actually important in life’, he said, such as health, relationship, and lifestyle stories that offer a reader-service component.

4. Collaboration and Community Impact

Even as the transition to digital news challenges geographic ties, local news organisations highlight the trust they have cultivated with readers and their distinctive ability to address local problems and suggest solutions (Jenkins and Nielsen 2018).2 Many local journalists also embrace community-centred approaches to reporting, such as advocacy and solutions journalism (Ali et al. 2018).

The collaborative initiatives explored in this report reflect this wider emphasis on building, reflecting the needs of, and working alongside communities. Participants said these efforts allow them to better connect with readers, enhance the reach of their reporting, and potentially create impact in the form of public dialogue and responses from political leaders.

This chapter focuses on the strategies collaboration participants use to better understand, tell the stories of, and connect with their communities. It then addresses the impact collaboration participants perceive their work is having, both at the local and national levels.

Connecting with Communities

Although all of the collaboration examples reflect networked approaches in which participants from across a country contribute content to reveal national trends, they also aim to allow local journalists to better cover their areas. Participants use strategies such as working alongside local grassroots and non-profit organisations to tell stories, hosting public forums to discuss local issues, and even creating a stage show to illustrate the implications of an investigation topic.

The Bureau Local: Bringing the Community into Local Reporting

The Bureau Local worked with campaigners, civil society groups, NGOs, members of Parliament, and other individuals and organisations to develop its recent investigations into homeless deaths and domestic violence refuges and better report on what they see as key concerns facing their communities. They also hold collaborative reporting days to draw people together with knowledge of and experience with different issues.

Director Megan Lucero said this emphasis on working within communities to tell stories is central to the aims of the Bureau Local and allows the network to build trust with those directly affected by the topics they investigate.

If you want to have accountability, you need to bring in all the players in the process. … We care about who is affected by the issue, who is embedded or knows the issue very deeply, who is causing the issue, who’s part of the issue, and then who can change the issue? These are the key players we ideally want to collaborate with.

When the Bureau Local began its investigation into local council spending in autumn 2017, they were overwhelmed by the amount of data compiled on the extent of proposed cuts and possible implications for public services. Lucero said they asked, ‘How do we narrow it to what actually matters to people?’ In response, they hosted an expert roundtable, including members of a women’s budget group and finance directors from a local council, to identify key problems to address.

The Bureau Local has also relied on non-traditional venues to tell its stories. As part of its domestic violence investigation, the journalists collaborated with a survivor, Cash Carraway, who wanted to share her story in the form of a touring stage show, Refuge Woman (see Figure 5). The Bureau supported the show, which travelled around the country and included a panel discussion during which journalists discussed their experiences reporting on domestic violence and budget cuts facing refuges.

Figure 5. A poster advertising Refuge Woman, a semi-autobiographical, one-woman play about life in a domestic violence refuge

Carraway’s presentation also included a critique of how the media interact with and report on victims, which Rachel Hamada, a community organiser for the Bureau Local, said ‘reversed the narrative’ and forced journalists to look back at themselves. She said the show also drew emotional responses from audience members.

[There were] very powerful comments from women who had gone through this themselves but also from people who’d come along … and been hugely affected and hugely hit by what they’d heard during the evening. It’s hard to come out of that and not feel something.

Emma Pearson, News Editor with the Lancashire Post, participated in the panel discussion at the Lancaster performance of Refuge Woman. She said the experience was important for making connections and continuing to report on the challenges facing domestic violence victims:

We did a Q&A session around it with local groups, and that was good just for building contacts and meeting people that we wouldn’t have met otherwise, so it carried on for quite a long time afterwards because what I think most papers tend to do is work very hard on a project, put it in the paper, and then forget about it. So, it kept giving for quite a few months afterwards, so that was good as well.

Emma Youle, a special correspondent for HuffPost UK who formerly worked with the Archant Investigations Unit, also participated in a Refuge Woman panel discussion and said it helped her better understand how the experience of dealing with the press impacts on survivors of domestic violence. In the performance, Carraway said she appreciated that when she was interviewed for the Bureau Local investigation, the journalist focused on budget cuts to refuge provision and its implications, rather than emphasising her experience as a victim. Youle said:

It was a real eye-opener to hear how somebody had felt about being on the receiving end of the questions journalists ask when reporting a story like that, and to think about the way that you try to represent other people’s stories and do that without taking their story away from them.

Lucero said journalists should embrace opportunities to work alongside invested community members to enhance accountability reporting.

I think journalism has been afraid to touch that space because you think, oh, we’re not activists. I need to have an objective approach. Journalists are humans. Journalists are not robots. You have perspective, but it’s about consciously putting forward the aim to seek the truth and to see both sides, and you have to hear all perspectives. So it’s about bringing them [the community] into it.

The Bureau is also working to connect local journalists with engagement experts who can conduct clinics or provide tools on how to work with communities, Hamada said.

Another thing that we’re looking at is something like community engagement recipes. Just as we have reporting recipes, helping people have quite structured ways of thinking through how they can work with their various local communities, to make sure that they’re getting genuine input locally, not just speaking to the same people over and over again, which, especially if you’re time poor, it’s easy for that to happen.

‘L’Italia Delle Slot’: Topic-Driven Partnerships

Covering the prevalence and implications of slot machines in Italy required not only working with the GEDI Group and its newspapers but also seeking out the perspectives of local civic groups, health organisations, NGOs, and academics invested in the issue.

Dataninja founder Alessio Cimarelli said he prefers to work on projects that focus on identifying an important issue, gathering and analysing data to provide context, working with news organisations to ask questions about the topic, and then helping newspapers to share these findings with readers in an engaging way. He suggested that in some cases, journalists and activists can work together, but transparency is always key. These efforts can be particularly effective at the local level, where the local newspaper and local organisations can work together on topics affecting local citizens, he said.

We are very happy to collaborate with different newspapers, different groups, different news companies, on a large project. Because some projects and issues can be phased only at the big level, it needs resources in time and in skills. Some topics, it would be very interesting to see a partnership from a newspaper and an NGO, so civic activists interested in one specific topic. And then I think that the newspaper can go with the organised citizens on a topics basis and start to build a community around the topic, start with an already structured organisation of the citizens.

Effecinque founder Raffaele Mastrolonardo said that while he and Cimarelli refrain from taking a particular stance on issues, they remain passionate about the need to make the data available and accessible to a wide audience.

We’re just saying that supporting the slot machines, or challenging the slot machines, you need information in order to make informed decisions through an informed public debate. The public needs to be informed. Slot machines and gambling are a huge thing with big economic, health, and cultural implications, and this issue is a political issue. … So our mission was, and is, to provide the public with the data that should enable more informed decisions about it.

Lännen Media: Avoiding ‘False Locality’

Editors with Lännen Media see their dispersed network of reporters as a resource that allows them to become engaged with issues and people in different parts of Finland.

A Lännen Media journalist said this strategy is ‘good for news’ because it ensures that when big news happens, a reporter is ready to get local perspectives.

A couple of years ago, there were big problems with the Talvivaara mine, and there was an environmental catastrophe that was really big news. It was really good that we had a Lännen Media journalist in Kajaani because she already knew all the local things, she knew the people, and she was near the place where everything happened. Because here in Helsinki, 600 kilometers from Sotkamo, we write what specialists or experts said, but she was really in the place where it happened.

Although Lännen Media reporters are headquartered in multiple cities, because they focus on writing articles to reach broad audiences, they are careful not to overemphasise location in their reporting, instead focusing on sources and topics with broad interest and appeal.

Theme Editor Riikka Happonen said she and her team avoid ‘false locality’ when choosing sources for features, that is, they are careful to feature people whose stories will be interesting to readers from anywhere in the country, regardless of where the story takes place. Happonen said they ‘find those kinds of people that their story is so interesting that they don’t become that false locality, if you understand. But I think we have been able to solve these problems, but we think of that every day.’