| Statistics | |

| Population | 31m |

| Internet penetration | 70% |

Zaharom Nain

Centre for the Study of Communications and Culture, University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus

The media environment in Malaysia remains a heavily controlled and censored one, strictly monitored and policed by an authoritarian regime.

Traditional media ownership in Malaysia is heavily concentrated in the hands of institutions and local conglomerates that are aligned to or owned by the Barisan Nasional (BN) government. One corporation, Media Prima, owns all four of Malaysia’s free-to-air commercial television stations and three newspapers (Harian Metro, Berita Harian, the New Straits Times). Media Prima is an investment company of the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), the dominant political party in the ruling BN coalition. The largest circulation English-language newspaper, The Star, is owned by the Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA), another key party of the BN.

There is a slew of laws that constrain both traditional and online media from being critical of the regime. One of these, the Sedition Act (1948), was widely used in 2015 and 2016, leading to the detention of more than 150 Malaysians, including journalists.

Despite these political, legal, and economic constraints, the internet and social media have continued to grow after the regime launched the Malaysian Multimedia Super Corridor (MSC) in 1996. Internet penetration rates have increased tremendously since then, while internet news media, like Malaysiakini, FreeMalaysiaToday, and the new The Malaysian Insight, have captured the imagination of an increasingly urbanised Malaysian public. Many have attributed this growth to the Bill of Guarantees that came with the launch; a pledge by the regime that the internet will not be censored. However, use of other legal constraints – including the Sedition Act – to harass and detain journalists, academics, politicians, and activists has, in reality, voided that `guarantee’.

2016 witnessed one of the most unfortunate closures in the Malaysian media industry, that of The Malaysian Insider (TMI), a news portal that, since its establishment in 2007, had risen rapidly to rival the more established Malaysiakini (est. 1999). The official reason for the closure was economic, as TMI was incurring extensive losses that its financial backers, the Edge Group, could not sustain. However, political reasons were also clearly evident, with the site having been blocked by the Malaysian Communication and Multimedia Commission (MCMC), the state regulatory body.1

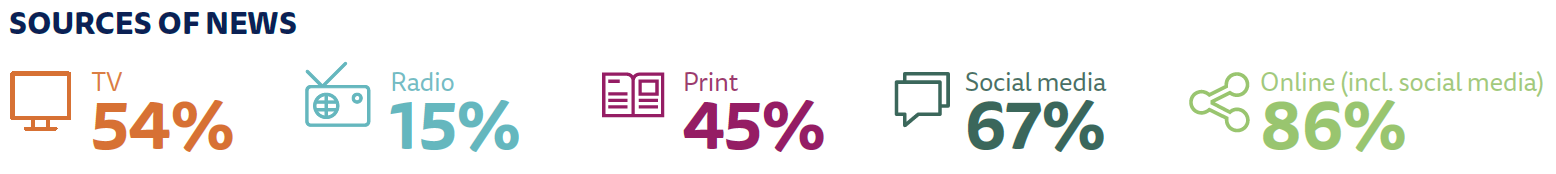

Television news continues to hold on to audiences, especially in the rural areas, often described as `the Malay heartland’. Over the past year, the commercial TV station, TV3, has continued to dominate the airwaves, not necessarily because of its news content but because of its more catchy presentation style – predominantly aimed at a rural, ethnic Malay audience – which has enabled it to do better than the staid, state-owned television station Radio Television Malaysia (RTM) for more than two decades.

Newspaper circulation continued to fall in 2016, with the English-language New Straits Times and once hugely popular Malay daily, Utusan Malaysia, recording ongoing losses. Both newspapers have not recovered from their loss of credibility from the late 1990s onwards. Their unyielding support of the regime, despite the latter being hit by a series of scandals in 2016, made them lose large segments of the rising middle-class Malaysian audience.

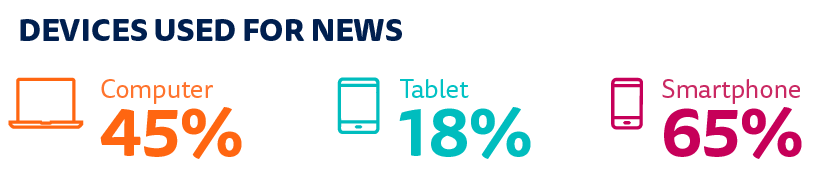

Malaysia’s growing internet penetration rate is certainly one of the main reasons why online news portals have become the medium of choice for many for a variety of news – amusing, complex, opinionated, and even political. Indeed, three factors are central to this development: the declining credibility of the mainstream media, the spread of a purportedly `free’ and `independent’ digital media environment, and the easier and more-immediate access to these news sources.

`Fake news’ has been around in Malaysia for years. For opposition groups, the term describes regime propaganda; something that has been churned out since at least the 1960s when state television was introduced into Malaysia and when UMNO took ownership of the Utusan media group. The regime, on the other hand, clearly capitalising on recent Western official critiques of fake news, has turned the argument around to help counter questions and critiques posed by news portals such Malaysiakini, the London-based Sarawak Report, and even international news agencies. A new portal, Sebenarnya (the truth), was set up in March this year by the MCMC purportedly to enable Malaysians to check the validity of news.2 There has been talk also of greater legal policing of social media and new legislation is anticipated in 2017.

Changing Media

Trust

The Malaysian public has trust issues with local media. State/regime ownership and control of much of these media, coupled with their constant manufacturing of falsehoods and crude regime propaganda, are the main reasons for this distrust. Many subsequently turn to social media for news.

- BBC News, Blocked Malaysian Insider News Website Shuts Down (Mar. 2016): http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-35800396 ↩

- http://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2017/03/14/sebenarnya-portal ↩