In this chapter, we explore the rise of the use of messaging apps for news and how this is related to decline in Facebook use for news. As seen in the Executive Summary of this report, the use of Facebook for news has been falling since 2016 in many countries, especially in some that have been affected by public debate over misinformation. At the same time, more people have been using messaging apps such as WhatsApp for any purpose (44%), while average usage for news has more than doubled to 16% in four years.

In terms of definition, it can be hard to separate social networks from messaging applications, though we have attempted to do so on the basis of whether they are principally used for messaging or not. Twitter and Instagram, of course, have messaging built into their service but it is not their primary purpose. Snapchat started as an app for ephemeral messaging but has now developed a richer feature set.

In the US, which is one of the countries with the steepest decrease in Facebook use for news, we can see that this is much greater among young users (14 percentage points difference between 2016 and 2018) whereas among the oldest age group there are no differences reported. At the same time, use of messenger apps for news (WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, Viber, Telegram, etc.) has grown with all groups but under 35s are the heaviest users.

When looking at different news-related activities on Facebook and WhatsApp, we find that Facebook is most likely to be used for reading or discovering news, either by glancing at headlines or clicking to read a full story. On WhatsApp, users are more likely to take part in a private discussion about news (24%) or to take part in a group set up specifically to discuss a news topic (16%).

Focus groups, held in the US, UK, Brazil and Germany, give us more insight this year about why messaging apps might be better at facilitating interaction and discussion. Users said that they have groups set up for friends, family or work and that they can chat and post articles about all sorts of topics including news more freely:

The whole thing about social media is like wearing a mask. So when I am in my messaging groups with my friends the mask comes off and I feel like I can truly be myself

(F, 30-45, UK)

But the use of social networks and messaging apps for news is not mutually exclusive. Respondents often talked about coming across news via Facebook or Twitter, but then posting it on WhatsApp when they wanted a discussion or debate:

Somehow WhatsApp seems a lot more private. Like it’s kind of a hybrid between texting and social media. Whereas in Facebook, for some reason it just feels like it’s public. Even if you’re in Messenger.

(F, 20-29, US)

The source is still Facebook because when we’re going to share something on WhatsApp, usually the article we’ve found it on Facebook. So Facebook is still king in that sense.

(M, 20-29, US)

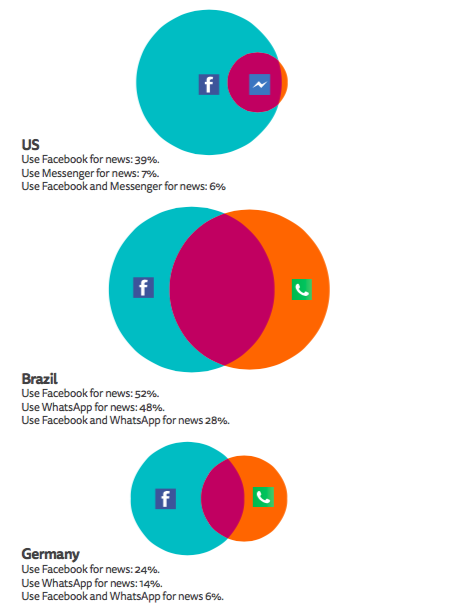

The majority of those who use messaging apps for news also use Facebook for news. This is particularly the case in the United States where Facebook Messenger dominates and WhatsApp is rarely used. But in Brazil and Germany, where WhatsApp is widespread, there is slightly less overlap with Facebook. In these markets more reading and sharing seems to have moved to WhatsApp as well as discussion — at least for some people.

OVERLAP IN USE OF FACEBOOK AND MESSAGING APPS FOR NEWS

Selected markets

Q12B. Which, if any, of the following have you used in the last week for news?

Base: Total sample in each market.

Across a wider set of countries, we find that the use of Facebook Messenger for news is high in a few countries like Greece or Norway where it is the dominant messaging app for news or for all purposes. However, in most countries, WhatsApp is the dominant messaging app, particularly in Latin American, Southeast Asian, and Southern European countries.

Elsewhere we see a range of other messaging apps that are not owned or operated by Facebook. Viber is the most popular messaging app in a number of Balkan countries where it is used for news by 14% in Bulgaria and Greece and 12% in Croatia. Line is widely used in Taiwan (73% for any purpose, 53% for news), while it is also the most popular messaging application in Japan (27% for any purpose, 9% for news).

WeChat is widely used in Hong Kong (52% for all purposes and 15% for news) and Malaysia (28% for all purposes and 10% for news). Kakao Talk is the dominant messaging app in South Korea used by the large majority of online news users (39% also use it for news). Telegram use is increasing but still at low levels. It has doubled since 2016 in the 26 countries of the 2016 sample, reaching 3% in 2018. However Telegram, whose main feature is strong encryption, is particularly popular in more authoritarian countries such as Malaysia (21% use it for all purposes and 9% for news) and Singapore (19% for all purposes and 6% use it for news).

Privacy is an important issue for users, and this partly explains the growth in use of messaging apps, as opposed to more open social networks. As noted in the Executive Summary, users in some ‘less free’ countries are more likely to think carefully before expressing their political views online. However, we can see that people also turn to messaging apps in non-authoritarian countries. One reason is that they do not always feel comfortable in expressing their political views in front of friends, family, and acquaintances. In countries like Japan, Norway, the US, or the UK (see chart), more people are concerned that their immediate or outer social circle will think differently about them,1 and that can be a reason why more people are using messaging apps for news.

Overall, these findings highlight the move of audiences, particularly younger groups, to more private apps for reading and particularly discussing news. However, as the findings suggest, large and less private social networks (mainly Facebook) are still largely used for finding and reading news stories. If these trends towards messaging apps are strengthened, it could create new dilemmas for publishers around being able to engage with ordinary citizens. The shift to messaging apps is partly driven by a desire for greater privacy, so pushing news into these spaces needs to be more organic and more conversational if it is to be accepted. In any case, setting up broadcast lists in WhatsApp is a complex and labour-intensive process (publishers have to provide a phone number2 which users then subscribe to). However, journalists have effectively used WhatsApp groups to distribute news when covering political development in places with censorship.3 Facebook Messenger makes it easier for publishers to create branded spaces and conversational interfaces but users have so far proved reluctant to sign up. Finally, if more immediate and intelligent discussion moves to messaging apps, this could make Facebook and Twitter comments even less representative of general users than they already are.

- A phenomenon called ‘context collapse’ by danah boyd, ‘Faceted Id/entity: Managing Representation in a Digital World’, MA thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, 2002, ↩

- E.g. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-30821245 ↩

- https://www.cjr.org/tow_center_reports/foreign_correspondents_chat_apps_unrest.php ↩