The political landscape of many Western countries is changing. As long-standing political parties fade, populists make significant gains at the ballot box – even taking power in some cases. In response, people have started to search for causes and, as is often the case, some have looked to the influence of the news media.

Understanding the influence of the news media on people’s political attitudes is far from easy, and we should rarely expect to find straightforward causal links. Nonetheless, a useful first step is to build a better understanding of how different groups within society access news.

In this section we will explore whether people with populist attitudes in Europe and the US have different media habits to the rest of the population.1 In particular, we will describe how they arrive at news, how they interact with it, and what outlets they rely on. We will also show how newer, more partisan, and alternative news outlets are carving out audiences from the gaps left by established news media.

Defining Populism

Inspired by recent cross-national research, we identified those with populist attitudes based on their belief in: (i) the existence of a ‘bad’ elite and the ‘virtuous’ people – two separate groups with competing interests, and (ii) the ultimate sovereignty of the will of the people (Pew Center 2018). We tapped the first dimension by asking people whether they agree (on a five-point scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’) that ‘most elected officials don’t care what people like me think’, and the second by asking whether ‘the people should be asked whenever important decisions are taken’. For the purposes of the analysis here, those that selected ‘tend to agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ for both of these statements were placed in the ‘populist attitudes’ group, with all other respondents placed in the ‘non-populist attitudes’ group.

People have different views about what populism is. Some argue that populism is nothing more than a style of communication. Others see populism as a ‘thin’ ideology, best understood in combination with more comprehensive belief systems such as left–right (Mudde 2004). We will turn to this later, but given that those with populist attitudes do appear to have distinct media habits that are relatively consistent across countries, we will proceed with this simple distinction for now.

Populist Attitudes in Different Countries

The proportion of the online population that agreed to both statements varies from country to country. Figures range from just under half in the Netherlands (49%), the UK (45%), Norway (49%), and Denmark (42%), to around three-quarters in Slovakia (71%), Greece (71%), Portugal (73%), and Croatia (77%). In the US, 54% of those surveyed agreed with both of the above statements.

This suggests that populist attitudes are less widespread in Northern and Western European countries than in Eastern and Southern Europe. In almost every country we analysed, populist attitudes are more common among those either in the older age groups, with lower incomes, or with lower levels of formal education.

Those with Populist Attitudes Prefer Television over Online News

Despite concern that the rise of populism is being driven by online media, when it comes to news, those with populist attitudes prefer offline news use – especially TV. Of those with populist attitudes 46% say that television is their main source of news, compared to 40% of those without. This preference is stronger for commercial television outlets, but weaker for public service broadcasters. Indeed, public service media have been a particular target for negative attacks from populists as their influence has grown in recent years (Cushion 2018).

Those with Populist Attitudes are Heavy Facebook News Users

Nonetheless, online news access is clearly important for those with populist attitudes, as well as for those without. If we drill deeper and look at the different ways people arrive at news online, we see many similarities between these groups – but also key differences. In Europe, directly accessing a branded website or app is the single most popular way of arriving at online news for those with populist attitudes (31%) and for those without (35%). However, those with populist attitudes have a stronger preference for social media (24% compared to 19%). In the US, social media ties with direct access as the main way of arriving at news for those with populist attitudes. There’s also no clear preference for direct access among those without populist attitudes.

The preference for social media among those with populist attitudes is largely due to a preference for Facebook. This group is more likely to use Facebook as a source of news, but no more likely to use other social networks like Twitter. Furthermore, our data also suggest that this gap may be growing. As a group, those with populist attitudes say they have started spending more time on Facebook in the past 12 months, whereas everyone else says they are spending less. This pattern makes sense if we think of Facebook as a network that primarily surfaces content based on the preferences of ordinary citizens, as opposed to Twitter, which many see as being dominated by elite voices, the established news media, and a relatively small and generally more privileged user base.

People with populist attitudes are also more likely to share and comment on news more when using social networks. Other studies have found that populist parties tend to be more active on Facebook – posting more, and generating more interactions with their content than established parties.2 These trends could be combining to create a social media environment where populist ideas and perspectives are over-represented – however it is not possible to conclude this from our data alone. So far, there’s little evidence that the growth of populism is being primarily driven by the popularity of social media – but it may be the case that people’s discontent with the established media is prompting people to rely more on social media for news (Schulz 2019).

Populist Attitudes and News Outlet Selection

Our data also show that those with populist attitudes gravitate towards different news outlets, and thus have different news diets. If we take our cross-platform data (online use combined with offline use) from the UK as an example, we can see that some outlets are more widely used by those with populist attitudes than those without, and vice versa. People who hold populist views are significantly more likely to use ITV, the Mirror, the Express, and the Sun, but those without populist attitudes are more likely to rely on the FT, Channel 4, the Telegraph, the Times, the Guardian, and the BBC. Audiences for other brands – including the Mail and Sky – are roughly evenly split.

This pattern reflects a preference for commercial TV and tabloid newspapers among those with populist attitudes. Those without, on the other hand, seem to prefer broadsheet newspaper brands and public service media. Some digital-born sites like HuffPost and BuzzFeed tend to have news audiences that are fairly evenly split. Other outlets however – particularly those we have previously referred to as alternative or partisan outlets – are often favoured by those with populist views, in addition to having audiences with a heavy left–right skew.

It is also noticeable how populist preferences cut across left–right divides, highlighting new dimensions along which news audiences can be segmented. For example, those with populist attitudes exhibit a clear preference for both the right-leaning Sun and the left-leaning Mirror. Similarly, those without populist attitudes have a preference for both the Guardian and the Telegraph – two newspapers with very different editorial lines.

Populism and News Audience Polarisation

Given these different usage patterns, we might wonder whether news audiences are polarised according to populist attitudes. In other words, to what extent do those with populist attitudes consume news from one set of outlets, and those without from another?

In our 2017 report, we explored how individual left–right preferences created a large degree of news audience polarisation in some countries, but not in others. We saw that in US, the UK, and in Southern and Eastern Europe, audiences for news outlets are often heavily right- or left-leaning – with relatively few outlets able to attract people of different persuasions. Whereas in other countries – typically those in Western and Northern Europe – news outlets had mixed audiences made up centrists, those on the left, and those on the right.

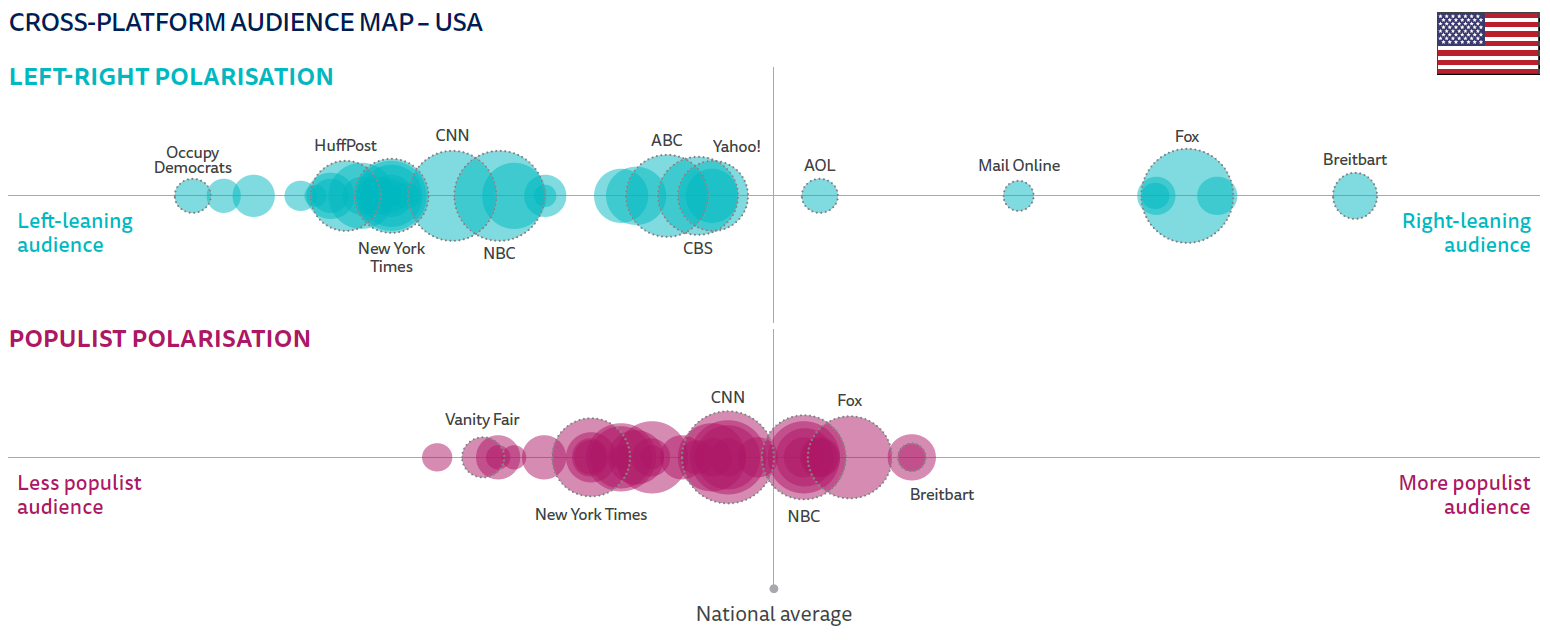

In the charts below, we compare the degree to which countries have strong left- or right-leaning audiences, with the degree to which they have strong populist or non-populist audiences. In the UK and the US – as in most countries – the extent of left–right polarisation is greater than the level of populist polarisation. The UK – with its prominent tabloid press – is home to outlets with relatively large populist audiences, but given that some outlets have audiences with a higher proportion of left- or right-leaning people (indicated by their distance from the centre of the map), it’s arguably true that left–right preferences are more important to people when deciding what news outlets to use. This is even more so in the US, where the degree of left–right polarisation is particularly strong.

CROSS-PLATFORM AUDIENCE MAP

United Kingdom

United States of America

Q1F. Some people talk about ‘left’, ‘right’, and ‘centre’ to describe parties and politicians. With this in mind, where would you place yourself on the following scale?

Q5A/B. Which of the following brands have you used to access news offline/online in the last week?

Base: Total sample: UK = 2023, USA = 2012.

In Germany, we see a different pattern. Here, the level of populist news audience polarisation is broadly similar to the US and the UK, but because the degree of left–right polarisation is low due to a general reluctance from the German news media to adopt partisan positions, populist attitudes have become more important to people when deciding what outlets to use.

CROSS-PLATFORM AUDIENCE MAP

Germany

Q1F. Some people talk about ‘left’, ‘right’, and ‘centre’ to describe parties and politicians. With this in mind, where would you place yourself on the following scale?

Q5A/B. Which of the following brands have you used to access news offline/online in the last week?

Base: Total sample: Germany = 2022.

Mapping News Audiences along Two Dimensions

Although some assume populism to be closely aligned with the right, scholars tend to see populism as a thin ideology that can be combined with both left- and right-wing views. Within each country we can essentially merge the above maps to identify outlets with populist left or populist right audiences.

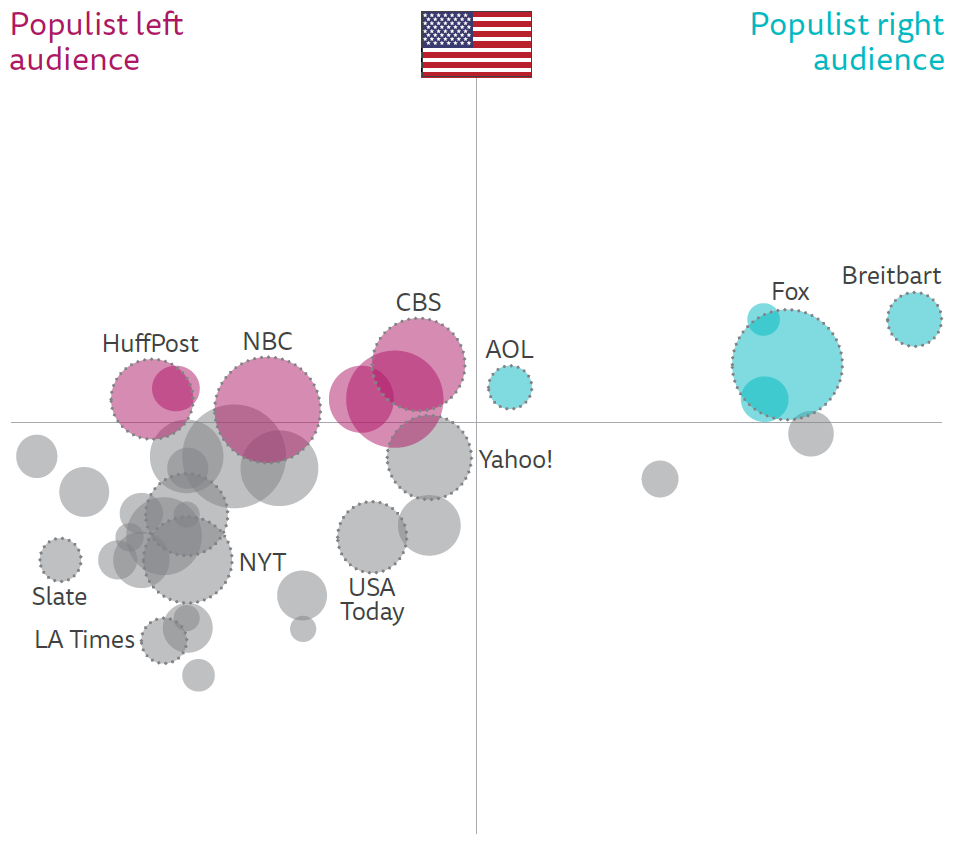

When we do this, a number of interesting patterns emerge. The position of each outlet along the horizontal axis indicates whether it has a left-leaning or right-leaning audience, with the distance from the centre indicating the strength of the skew. The position on the vertical axis indicates whether the outlet has a populist audience. The higher the outlet, the more its audience is skewed towards those with populist attitudes. Outlets with populist left audiences are coloured red, and outlets with populist-right audiences are coloured blue.

The US and the UK both contain a mixture of outlets with populist left and populist right audiences. The Mirror, for example, clearly has an audience that is predominantly made up of people who self-identify on the left, and who also hold populist attitudes. Readers of the Sun also tend to hold populist attitudes, but self-identify on the right.

In the US, though there are some outlets with populist audiences – such as Fox and HuffPost – it is also clear that the majority of outlets have audiences that are predominantly non-populist left, such as the New York Times. It is also clear that none of the outlets we examined in the US have audiences that are as skewed towards populists as in the UK. It may be that the inability or unwillingness of the established news media in the US to connect with those with populist attitudes has created a ‘populist vacuum’ – which may explain why many turn to social media and talk radio for news and information.

CROSS-PLATFORM AUDIENCE MAP

UK and USA

Q1F. Some people talk about ‘left’, ‘right’, and ‘centre’ to describe parties and politicians. With this in mind, where would you place yourself on the following scale?

Q5A/B. Which of the following brands have you used to access news offline/online in the last week?

Base: Total sample: UK = 2023, USA = 2012.

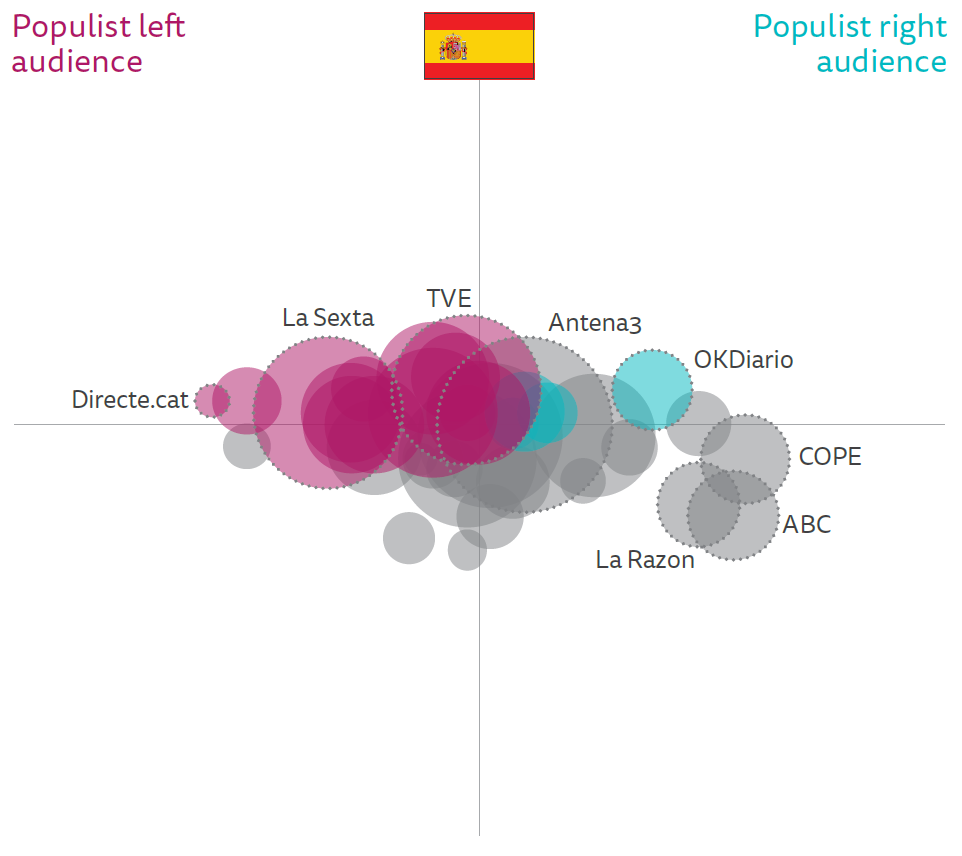

Not every country has this relatively even balance between populist left and populist right audiences. In Germany, we did not find any outlets with a populist left audience in our data. However, a considerable number of outlets have populist right audiences, particularly commercial television channels like Sat.1 and RTL. In Spain we see the opposite. Here, there are several outlets with populist left audiences, but only a handful on the right. It is perhaps no coincidence that Spain has also seen one of the strongest populist left political movements in recent years, though the populist right did well in 2019 elections.

CROSS-PLATFORM AUDIENCE MAP

Germany and Spain

Q1F. Some people talk about ‘left’, ‘right’, and ‘centre’ to describe parties and politicians. With this in mind, where would you place yourself on the following scale?

Q5A/B. Which of the following brands have you used to access news offline/online in the last week?

Base: Total sample: Germany = 2022, Spain = 2005.

The maps we have shown so far also contain partisan and alternative news websites – such as the Canary in the UK and Breitbart in the US. These outlets usually have very left- or right-leaning audiences, but as is clear from the maps, they often have very populist audiences as well. Breitbart has the most populist audience in our US dataset, and the Canary’s audience is also more likely to hold populist views.

Sweden contains some extreme examples of this phenomenon. Outlets like Fria Tider are used by around 10% of the online population, and have audiences that are heavily skewed towards those that both self-identify on the right and hold populist views. These outlets are sometimes understood as anti-immigration, but are also critical of political elites and the criminal justice system (Nygaard 2019). Their tone and style of coverage is a clear departure from the norms that govern the established television and newspaper outlets in Sweden.

CROSS-PLATFORM AUDIENCE MAP

Sweden

Q1F. Some people talk about ‘left’, ‘right’, and ‘centre’ to describe parties and politicians. With this in mind, where would you place yourself on the following scale?

Q5A/B. Which of the following brands have you used to access news offline/online in the last week?

Base: Total sample: Sweden = 2007.

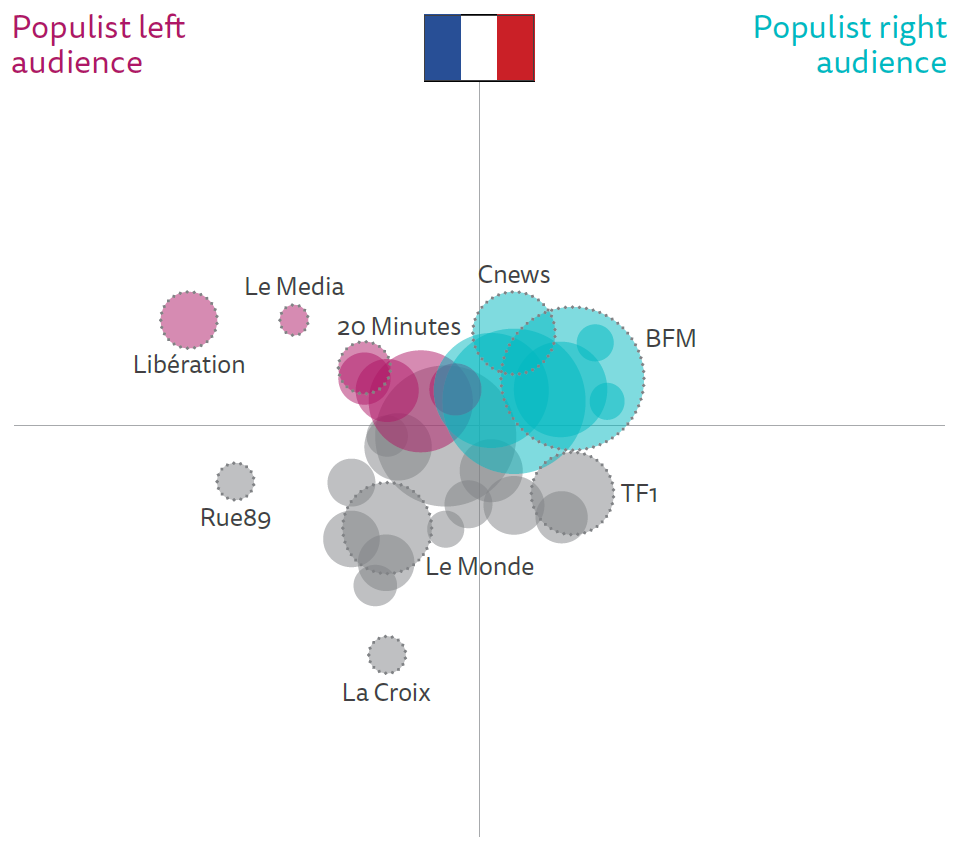

In France and Italy, perhaps the most notable feature of the maps is that the most popular outlets also have a higher than average number of people with populist attitudes in their audience. These are typically commercial television channels, again highlighting the link between populist attitudes and seeing TV as the main source of news.

We have not fully explored the links between populist attitudes and trust this year. But our data do show less of a trust gap between those with populist attitudes and those without populist attitudes in countries where the most popular news outlets have populist audiences. However, in countries where populist outlets are less prominent – often because public service media are dominant – populists are considerably less likely to think that they can trust most news most of the time. In short, people who do not find any news media that reflect their attitudes often trust all news media less.

CROSS-PLATFORM AUDIENCE MAP

France and Italy

Q1F. Some people talk about ‘left’, ‘right’, and ‘centre’ to describe parties and politicians. With this in mind, where would you place yourself on the following scale?

Q5A/B. Which of the following brands have you used to access news offline/online in the last week?

Base: Total sample: France = 2005, Italy = 2006.

It has become fashionable to dismiss left–right as an outdated concept that no longer explains people’s beliefs. But when it comes to news use, it is still able to explain a lot in both Europe and the US. Populism clearly matters too, but is best understood in combination with left–right self-identification.

A key question for publishers is how they will understand their own position within this two-dimensional space, especially as new partisan and alternative outlets carve out audiences from the spaces they have left vacant. A key question for public debate concerns what will happen if a significant minority is unable to find some, if any, established news outlets that reflect their attitudes, and instead turns to alternative and partisan outlets, and social media.

- Our data comes from the following 23 European countries: UK, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Belgium, Netherlands, Switzerland, Austria, Hungary, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, Croatia, and Greece. ↩

- https://www.politico.eu/article/europe-populists-european-election-alternative-for-deutschland-rassemblement-national-facebook/ ↩