Executive Summary and Key Findings of the 2020 Report

This year’s report comes in the midst of a global health pandemic that is unprecedented in modern times and whose economic, political, and social consequences are still unfolding. The seriousness of this crisis has reinforced the need for reliable, accurate journalism that can inform and educate populations, but it has also reminded us how open we have become to conspiracies and misinformation. Journalists no longer control access to information, while greater reliance on social media and other platforms give people access to a wider range of sources and ‘alternative facts’, some of which are at odds with official advice, misleading, or simply false.

Much of the data in this publication was collected before the virus hit many of the countries featured in this survey, so to a large extent this represents a snapshot of these historic trends. But to get a sense of what has changed, we repeated key parts of our survey in six countries (UK, USA, Germany, Spain, South Korea, and Argentina) in early April. These responses confirm industry data which show increased consumption of traditional sources of news, especially television, but also some online news sources.

Journalism matters and is in demand again. But one problem for publishers is that this extra interest is producing even less income – as advertisers brace for an inevitable recession and print revenue dips. Against this background it is likely we’ll see a further drive towards digital subscription and other reader payment models which have shown considerable promise in the last few years. This is what makes it so important to understand how various models are progressing in different markets, such as the United States, Norway, and the UK, where we have conducted more in-depth research on pay this year. While the coronavirus crisis is likely to dramatically affect the short-term prospects for many publishers, our findings provide long-term insights into one important part of the future of the business of news. We also ask about the implications for society if more high-quality information disappears behind paywalls, a dilemma that has become more real during this health emergency.

Looking to the future, publishers are increasingly recognising that long-term survival is likely to involve stronger and deeper connection with audiences online, which is why we have also examined the growing importance of emails and podcasts, formats that are being deployed in greater numbers to increase engagement and loyalty. The coronavirus crisis has presented an immediate and urgent existential threat, but in the section on climate change, we explore how audiences access news about this longer-term threat to human existence and how they feel about media coverage.

Our report this year, based on data from six continents and 40 markets, aims to cast light on the key issues that face the industry at a time of unprecedented uncertainty. The overall story is captured in this Executive Summary, followed by Section 2 with chapters containing additional analysis, and then individual country and market pages in Section 3 with detailed data and extra context.

A summary of some of the most important findings from our 2020 research

- The coronavirus crisis has substantially increased news consumption for mainstream media in all of the countries where we conducted surveys before and after the pandemic had taken effect. Television news and online sources have seen significant upticks, and more people identify television as their main source of news, providing temporary respite from a picture of steady decline. Consumption of printed newspapers, has fallen as lockdowns undermine physical distribution, almost certainly accelerating the shift to an all-digital future.

- At the same time, the use of online and social media substantially increased in most countries. WhatsApp saw the biggest growth in general with increases of around ten percentage points in some countries, while more than half of those surveyed (51%) used some kind of open or closed online group to connect, share information, or take part in a local support network.

- As of April 2020, trust in the media’s coverage of COVID-19 was relatively high in all countries, at a similar level to national governments and significantly higher than for individual politicians. Media trust was more than twice the level for social networks, video platforms, or messaging services when it came to information about COVID-19.

From our wider dataset collected in January:

- Global concerns about misinformation remain high. Even before the coronavirus crisis hit, more than half of our global sample said they were concerned about what is true or false on the internet when it comes to news. Domestic politicians are the single most frequently named source of misinformation, though in some countries – including the United States – people who self-identify as right-wing are more likely to blame the media – part of a pick-your-side Facebook is seen as the main channel for spreading false information almost everywhere but WhatsApp is seen as more responsible in parts of the Global South such as Brazil and Malaysia.

- In our January poll across countries, less than four in ten (38%) said they trust most news most of the time – a fall of four percentage points from 2019. Less than half (46%) said they trust the news they use themselves. Political polarisation linked to rising uncertainty seems to have undermined trust in public broadcasters in particular, which are losing support from political partisans from both the right and the left.

- Despite this, our survey shows that the majority (60%) still prefer news that has no particular point of view and that only a minority (28%) prefer news that shares or reinforces their views. Partisan preferences have slightly increased in the United States since we last asked this question in 2013 but even here a silent majority seems to be looking for news that at least tries to be objective.

- As the news media adapt to changing styles of political communication, most people (52%) would prefer them to prominently report false statements from politicians rather than not emphasise them (29%). People are less comfortable with political adverts via search engines and social media than they are with political adverts on TV, and most people (58%) would prefer platforms to block adverts that could contain inaccurate claims – even if it means they ultimately get to decide what is true.

- We have seen significant increases in payment for online news in a number of countries including the United States 20% (+4) and Norway 42% (+8), with smaller rises in a range of other markets. It is important to note that across all countries most people are still not paying for online news, even if some publishers have since reported a ‘coronavirus bump’.

- Overall, the most important factor for those who subscribe is the distinctiveness and quality of the content. Subscribers believe they are getting better information. However, a large number of people are perfectly content with the news they can access for free and we observe a very high proportion of non-subscribers (40% in the USA and 50% in the UK) who say that nothing could persuade them to pay.

- In countries with higher levels of payment (e.g. the USA and Norway) between a third and half of all subscriptions go to just a few big national brands – suggesting that winner-takes-most dynamics are persisting. But in both these countries a significant minority are now taking out more than one subscription, often adding a local or specialist publication.

- In most countries, local newspapers and their websites remain the top source of news about a particular town or region, reaching four in ten (44%) weekly. But we find that Facebook and other social media groups are now used on average by around a third (31%) for local news and information, putting further pressure on companies and their business models.

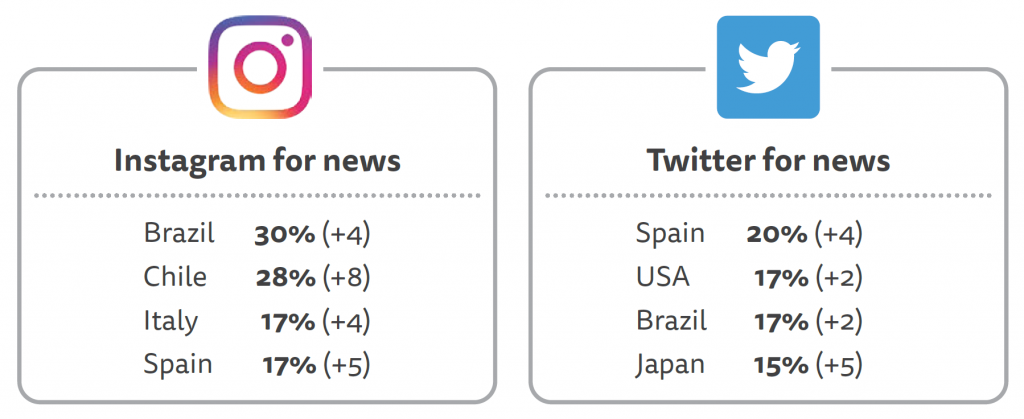

- Access to news continues to become more distributed. Across all countries, just over a quarter (28%) prefer to start their news journeys with a website or app. Those aged 18–24 (so-called Generation Z) have an even weaker connection with websites and apps and are more than twice as likely to prefer to access news via social media. Across age groups, use of Instagram for news has doubled since 2018 and looks likely to overtake Twitter over the next year.

- To counter the move to various platforms, publishers have been looking to build direct connections with consumers via email and mobile alerts. In the United States one in five (21%) access a news email weekly, and for almost half of these it is their primary way of accessing news. Northern European countries have been much slower to adopt email news channels, with only 10% using email news in Finland.

- The proportion using podcasts has grown significantly in the last year, though coronavirus lockdowns may have temporarily reversed this trend. Across countries, half of all respondents (50%) say that podcasts provide more depth and understanding than other types of media. Meanwhile, Spotify has become the number one destination for podcasts in a number of markets, overtaking Apple’s podcast app.

- Overall, almost seven in ten (69%) think climate change is a serious problem, but in the United States, Sweden, and Australia a significant minority dispute this. This group tends to be right-wing and older. Younger groups access much of their climate change news from social media and by following activists like Greta Thunberg.

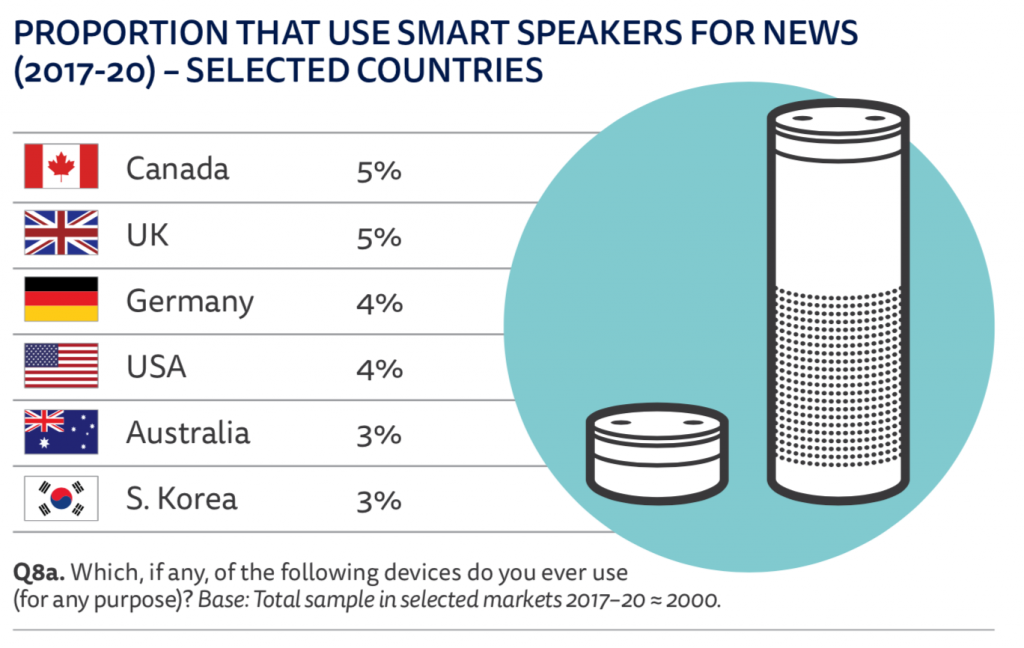

- Voice-activated smart speakers like the Amazon Echo and Google Home continue to grow rapidly. Usage for any purpose has risen from 14% to 19% in the UK, from 7% to 12% in Germany, and 9% to 13% in South Korea. Despite this, we find that usage for news remains low in all markets.

Coronavirus Reminds People of the Value of Traditional News Sources

Over the last nine years, our data have shown online news overtaking television as the most frequently used source of news in many of the countries covered by our online survey. At the same time, printed newspapers have continued to decline while social media have levelled off after a sharp rise.

The coronavirus crisis has significantly, though almost certainly temporarily, changed that picture. Television news has seen an uplift in all six countries where we polled in both January and April 2020. Taking Germany as an example (see chart), a 12-point decline in reach for TV news was partially reversed as many people turned to trusted sources of news including public service media.

Weekly TV news consumption rose by an average of five percentage points across all six countries. But it is worth noting that social media were also substantially up (+5) as more people used these networks for finding and sharing news in combination with television and online sites. By contrast, the lockdowns hit the reach of print newspapers and magazines with a six-point drop in Spain, not helped by difficulties in distributing physical copies.

The change of underlying preferences is even more clear when we ask people to choose their main source of news. The UK shows a 20-percentage-point switch in preference from online to TV between the end of January and the start of April, and Argentina 19 points, with the average across six countries being a change of 12 points.

In the UK, Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s address telling Britons to stay at home was one of the most-watched broadcasts in UK television history, with 27m tuning in live (excluding live streams via news websites and apps).1 Nightly viewership of BBC TV bulletins was up by around 30% in March while the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) reported daily viewing increases across countries of 14% in the early stages.2

The British prime minister’s address was shown on nearly all terrestrial channels and was also uploaded to YouTube and Amazon Prime. Photograph: REUTERS/Andrew Couldridge

The uplift in TV and social media was experienced across all age groups, with under-35s proportionally showing the biggest increase in use of television as well as for using social media to access news. In the UK, under-35s showed an increase in watching TV news of 23 percentage points compared with January, though their core preference for online and social media remained. Older groups read fewer newspapers and watched more television news.

By contrast to the UK experience, in countries with fewer widely used and broadly trusted sources, the television experience has been very different, with CNN and Fox News covering President Trump’s press conferences in fundamentally different ways, and some broadcasters refusing to transmit live from sessions where the President often goes directly against medical and scientific advice. In the United States we see less of a boost for television news overall, though a similar growth in usage from under-35s.

Industry data also indicate strong traffic increases for online news with the most trusted brands often benefitting disproportionately. The BBC reported its biggest week ever for UK visitors, with more than 70m unique browsers as the lockdown came into effect – though traffic has since returned to more normal levels.

Commercial media have also reported a significant increase in online traffic and have produced many examples of innovations in data journalism and other visual formats online to help explain the crisis. Websites and apps have included practical guides for managing isolation and staying safe.

EXPLANATORY AND DATA-RICH ONLINE COVERAGE FROM THE WASHINGTON POST

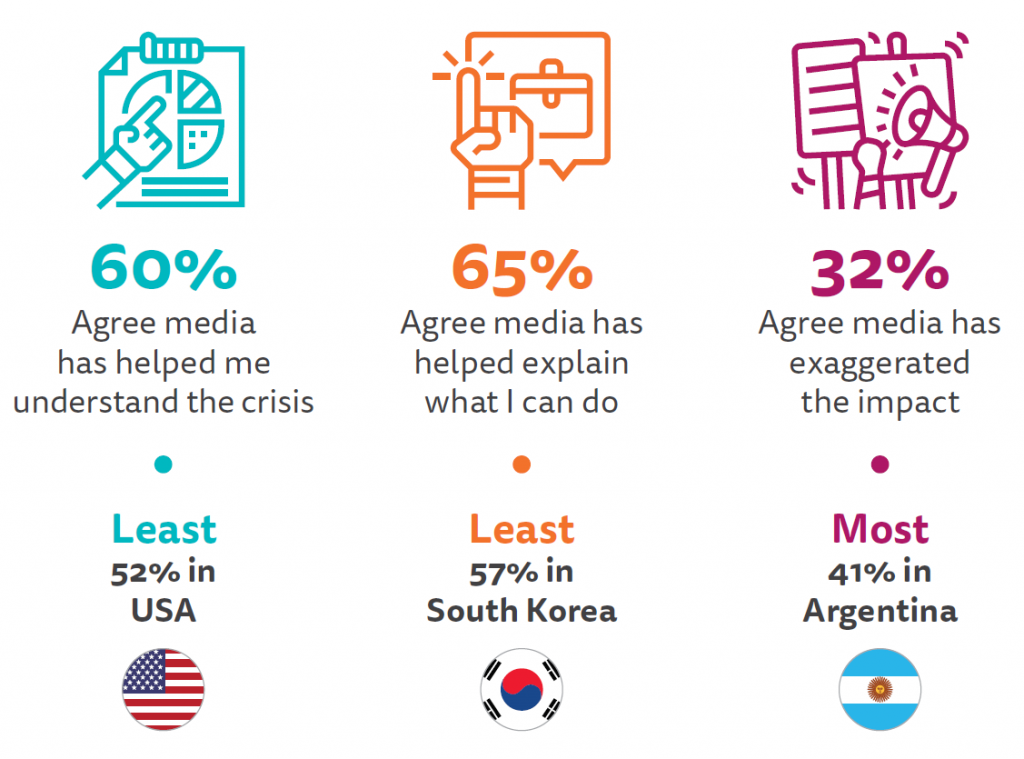

Overall our April 2020 survey found the news media were considered to have done a good job in helping ordinary people understand the extent of the crisis (60%), and also in making clear what people can do personally to mitigate the impact (65%). Though some media have in the past been accused of sensationalising stories, on this occasion only a third (32%) think that the media have exaggerated the severity of the situation, though concern was higher in the United States (38%) and Argentina (41%), and amongst those that distrust the media already.

ATTITUDES TOWARDS NEWS MEDIA COVERAGE OF CORONAVIRUS (APRIL 2020)

Selected countries

Q14 (Apr. 2020). To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements about the coronavirus (COVID-19)?

Base: Total sample: USA, UK, Germany, Spain, Argentina, S Korea = 8522.

And in terms of trust for information about coronavirus, national news organisations score relatively well, behind doctors and health organisations but ahead of individual politicians and ordinary people. In recent years some populist politicians in particular have taken to undermining the media but this coronavirus pandemic has been a reminder that even weakened media play a critical role in informing populations and shaping opinion.

At around the peak of the lockdowns, trust in news organisations around COVID-19 was running at more than twice that for social media, video sites, and messaging applications where around four in ten see information as untrustworthy. By contrast information found in search engines was seen as more reliable. Of course, neither search nor social companies create content themselves, so trust in this context is a reflection of the selection decisions they make.

It is particularly striking that average levels of trust in the national government and news organisations are almost identical, perhaps reflecting the way that in the early stages of this crisis many media organisations focused on amplifying government messages about health and social distancing, including carrying extended government press conferences. As things return to normal, the media are likely to become more critical of government and this may in turn lead to a return of more partisan approaches to media trust.

Social Media and the Crisis

While people are wary of social media and messaging apps, high usage may suggest that many people are confident in their own ability to spot misinformation or just that they value these platforms for other reasons, such as keeping in touch with family or friends, and for mutual support.

In April we found that across our six surveyed countries almost a quarter (24%) used WhatsApp to find, discuss, or share news about COVID-19 – up seven points on average on our January survey which asked about usage for any news. Around a fifth (18%) joined a support or discussion group with people they didn’t know on either Facebook or WhatsApp specifically to talk about COVID-19 and half (51%) took part in groups with colleagues, friends, or family. One in ten accessed closed video chats using platforms like Zoom, Houseparty, and Google Hangouts – many for the first time.

People applaud from their windows and balconies as they take part in an event organized through social media to show gratitude to healthcare workers during a partial lockdown as part of a 15-day state of emergency to combat the spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19), outside a pharmacy in Ronda, southern Spain, March 20, 2020. REUTERS/Jon Nazca

Meanwhile Instagram and Snapchat have become popular with younger groups for accessing news about COVID-19. Celebrities and influencers play an outsized role on these networks, with some sharing music, running exercise classes as well as commenting on the wider health issues. Almost half of our 18–24 respondents in Argentina (49%) used Instagram, 38% in Germany. One in ten (11%) accessed COVID-19 news via TikTok in the US and 9% in Argentina.

Social media may be helping to spread false and misleading information, but it has also supported people at a time of anxiety and isolation and provided an effective way to amplify reliable information. It is important to remember that social media are generally used in combination with other types of information. In the six countries we surveyed in April, more than four-in-ten (43%) accessed both social media for news and traditional media sources on a weekly basis. A more detailed analysis showed that, in most countries, those who relied on news organisations for information about coronavirus were more knowledgeable about the crisis, whereas there was no consistent, significant pattern for those who relied on various platforms including social media – they were not more informed but, despite some fears to the contrary, they were not misinformed either (Nielsen et al. 2020).

Lasting Effects?

Media habits changed significantly during the COVID-19 lockdowns even if levels of interest have proved hard to sustain.3 More people turned to live broadcast television news and to trusted news sources online, but the lockdowns have also accelerated the use of new digital tools, with many people joining online groups or taking part in video conferencing for the first time. Together with the impact on print production and distribution, it is likely that the net effect will be to speed up rather than slow down the shift to digital.

The implications for trust are harder to predict. In most countries the media played a largely supportive role in the early stages of the crisis – when lives were most at risk. But that consensus has already started to break down as normal activities resume and disagreements resurface about the best way to manage the recovery. Any ‘trust halo’ for the media may be also be short-lived.

Trust in the News Media Continues to Fall Globally

As the coronavirus hit, we observed overall levels of trust in the news at their lowest point since we started to track these data. In a direct comparison with 2019 we find that fewer than four in ten (38%) say they trust most news most of the time – down four percentage points. Less than half (46%) say they trust the news that they themselves use.

PROPORTION THAT TRUST EACH MOST OF THE TIME

All markets

Q6_1/2/3/4. Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements: I think you can trust most news/the news I use/news in search/news in social media most of the time.

Base: Total sample: All markets = 80,155.

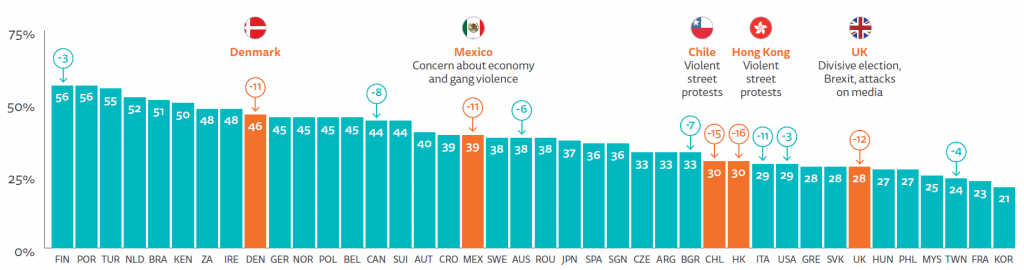

We continue to see considerable country differences, ranging from Finland and Portugal where over half (56%) say they trust most news most of the time, to less than a quarter in Taiwan (24%), France (23%), and South Korea (21%). Just six countries now have trust levels of more than 50%.

Notable changes over the last 12 months include a 16-percentage point fall in Hong Kong (30%) following violent street protests over a proposed extradition law. In Chile, which has seen regular demonstrations about inequality, the media has lost trust (-15) partly because it is seen as too close to the elites and not focusing its attention enough on underlying grievances.4

There were also significant falls in the United Kingdom (-12), Mexico (-11), Denmark (-11), Bulgaria (-7), Canada (-8), and Australia (-6) where our poll coincided with bitter debates over the handling of some of Australia’s worst-ever bush fires.

PROPORTION THAT AGREE THEY CAN TRUST MOST NEWS MOST OF THE TIME

All markets

Q6_1. Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: I think you can trust most news most of the time.

Base: Total sample in each market ≈ 2000, Taiwan = 1027

Divided societies seem to trust the media less, not necessarily because the journalism is worse but because people are generally dissatisfied with institutions in their countries and perhaps because news outlets carry more views that people disagree with.

One recent example of how this works came in the UK election in December 2019 where Boris Johnson asked the people to endorse his Brexit deal. The Tory victory came after a toxic political campaign where the media were heavily criticised by both sides (Fletcher et al. 2020). Many on the left blamed the Labour defeat on unfair media treatment of its leader Jeremy Corbyn by a ‘biased press’. The impact can be seen in the next chart with trust amongst respondents who self-identify on the left collapsing from 38% in January 2019 to just 15% a year later. Trust amongst those on the right also declined but by much less.

In the United States we observe the same picture but in reverse. It is the right that has lost trust, partly inflamed by the anti-media rhetoric of the president himself. A bruising Democratic Presidential Primary may help account for the decline in trust on the left.

Although the left has long had a problem with right-wing bias in the UK press, the Brexit crisis saw the public service BBC increasingly in the firing line. The BBC has a duty to be duly impartial in its news coverage but our data show that, although overall trust in its news remains high, criticism from those who are politically committed (on the left and the right) has grown over the last few years. Trust in the BBC with the most partisan groups has fallen by 20 percentage points since 2018.

Public service media remain by and large the most trusted brands, especially in Northern European countries where they have a strong tradition of independence. But criticisms from the extremes do seem to be chipping away at this confidence in many countries, especially when combined with anti-elitist rhetoric from populist politicians. Our country and market-based pages clearly show that, though trust remains high, distrust of public service media is growing and is often higher than for many other news brands.

Despite Partisan Pressures, Silent Majority Still Prefer ‘Objective’ News

Greater political polarisation has coincided with an explosion of low-cost internet publishing which in turn has led to the widespread availability of partisan opinions online. With news coverage increasingly commoditised, parts of the traditional media have also focused more on strong and distinctive opinion as a way of attracting and retaining audiences. Some commentators have increasingly questioned the value of objective news in a world where people have ready access to news from so many different points of view, while others worry that social media and algorithms are encouraging echo-chambers and pushing communities apart. In this context we were interested to know if consumer preferences for news that reinforce people’s views had grown since we last looked at this subject in 2013.

Looking across nine markets we see that the majority in each country say they prefer news with no particular point of view. In a sense this is not surprising given that traditional expectations are that journalists should produce neutral and detached news, but the differences between countries are striking.

This preference for neutral news is strongest in Germany, Japan, the UK, and Denmark – all countries with strong and independent public broadcasters. A preference for more partial news is strongest in Spain, France, and Italy – countries that scholars have labelled ‘polarised pluralist’ (Hallin and Mancini 2004) – as well in the United States.

Comparing 2020 with data from 2013, we see increased preference over time in the UK (+6) for news that has ‘no particular point of view’. At the same time, the proportion that prefers news that ‘shares their point of view’ has declined by a similar amount (-6). It is hard to be sure about the reasons, but one possibility is that a silent majority is reacting against a perceived increase in agenda-filled, biased, or opinion-based news. These themes came out strongly in comments from our survey respondents.

I prefer that news is delivered objectively so individuals are able to analyse what they have heard/read and come to their own conclusions without being unduly influenced.

Female, 61, UK

A Different Story in the United States

In the United States, where both politics and the media have become increasingly partisan over the years, we do find an increase in the proportion of people who say they prefer news that shares their point of view – up six percentage points since 2013 to 30%. This is driven by people on the far-left and the far-right who have both increased their preference for partial news sources.

PARTIAL TV AUDIENCES

In the USA, audiences for cable television networks, such as Fox on the right and CNN and MSNBC on the left, are strongly weighted to one view or another. At the same time, the influence of partisan websites (e.g. Breitbart, The Blaze, the Daily Caller, Occupy Democrats, Being Liberal) grew rapidly ahead of the 2016 election and even today around a quarter (23%) of our sample visits at least one of these each week. In our survey we asked respondents who said they prefer news that ‘shares their point of view’ to explain why they held that position. Many suggested that it helped avoid political arguments or because they felt they were getting closer to the truth:

I’m tired of hearing fake news from the dishonest left socialist commie traitors!!!

Female, 69, USA survey respondent

Because CNN, MSNBC tell the truth whereas Fox News is not bound by pure facts.

Female, 73, USA survey respondent

Complaints like this about the media have become increasingly vocal in recent years and yet it is striking that even in the United States a majority (60%) still express a preference for news without a particular point of view. We can also note that, during the coronavirus crisis, partisan websites and TV brands showed stagnant or low traffic growth compared with other brands.5

The Role of the News Source

It is interesting how people’s attitudes to objective, partial, or challenging news is related to the source of news they use most often. In the next chart we can see that in the USA people who regularly use strident 24-hour news channels like Fox and CNN are most likely to prefer partial news, followed by social media and then print.

In the UK we see the reverse picture, with people who use television as main source most likely to prefer neutral or objective news. This is not surprising given that television in the UK has an obligation to be duly impartial and is regulated accordingly. By contrast, those whose main source is a printed newspaper (or social media) are three times as likely to prefer news that shares their point of view. In Spain and Brazil, we see all three media sources being associated with a preference for partial news – and social media playing the biggest role.

Interpreting notions of objectivity is not an easy task at a time of rising political polarisation, even on issues in which the weight of scientific evidence overwhelmingly favours one side. Public media organisations like the BBC in the UK have faced criticism for adopting a ‘he said, she said’ approach to coverage of topics such as climate change as they seek to present both sides of arguments. Some UK news organisations have taken a different approach to these issues, with the Guardian adopting the term ‘climate emergency’ to describe the urgency of the story. Our recent qualitative study of news behaviours amongst under-35s showed that younger age groups in particular tend to respond well to approaches and treatments that take a clear point of view (Flamingo 2019). Our survey data also show that, across countries, young people are also less likely to favour news with no point of view.

In reality this is not a zero-sum game. Most people like to mix news that they can trust with a range of opinions that challenge or support their existing views. We do find, however, that those with extreme political views are significantly less attracted to objective news – and these are often the same people that are increasingly distrustful of mainstream media. Younger people are more ambivalent. They still turn to trusted mainstream brands at times of crisis but they also want authentic and powerful stories, and are less likely to be convinced by ‘he said, she said’ debates that involve false equivalence.

Misinformation and Disinformation

More than half (56%) of our sample across 40 countries remains concerned about what is real and fake on the internet when it comes to news. Concern tends to be highest in parts of the Global South such as Brazil (84%), Kenya (76%), and South Africa (72%) where social media use is high and traditional institutions are often weaker. Lowest levels of concern are in less polarised European countries like the Netherlands, Germany, and Denmark.

The biggest increase in concern came in Hong Kong this year (+6) as the conflict between the government and student protesters continued and also in Finland (+4), where we see higher than average concern over false and misleading information from foreign governments.

PROPORTION CONCERNED ABOUT WHAT IS REAL AND WHAT IS FAKE ON THE INTERNET WHEN IT COMES TO NEWS

All markets

Q_FAKE_NEWS_1. Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement. Thinking about online news, I am concerned about what is real and what is fake on the internet.

Base: Total sample in each market ≈ 2000, Taiwan = 1027.

Domestic politicians are seen as most responsible (40%) for false and misleading information online, followed by political activists (14%), journalists (13%), ordinary people (13%), and foreign governments (10%). Despite widespread media coverage of alleged attempts by outside powers to undermine elections it is striking that it is the rhetoric and behaviour of national politicians that is considered the biggest problem. This echoes arguments from scholars that misinformation often comes from the top (and not from ordinary people).

PROPORTION THAT SAY THEY ARE MOST CONCERNED ABOUT FALSE OR MISLEADING INFORMATION FROM EACH OF THE FOLLOWING

All markets

Q_FAKE_NEWS_2020b. Which of the following, if any, are you most concerned about online? False or misleading information from…

Base: Total sample = 80155.

We see a slightly different pattern in parts of Asia where the behaviour of ordinary people – for example, in sharing false information without considering the consequences – is considered the biggest problem in Japan (27%) and is second only to domestic politicians in Taiwan (29%).

But political starting positions can make a big difference when it comes to assigning responsibility for misinformation. In the most polarised countries, this effectively means picking your side. Left-leaning opponents of Donald Trump and Boris Johnson are far more likely to blame these politicians for spreading lies and half-truths online, while their right-leaning supporters are more likely to blame journalists. In the United States more than four in ten (43%) of those on the right blame journalists for misinformation – echoing the President’s anti-media rhetoric – compared with just 35% of this group saying they are most concerned about the behaviour of politicians. For people on the left the situation is reversed, with half (49%) blaming politicians and just 9% blaming journalists.

By contrast, in the Netherlands, there is less political polarisation and less picking of sides required, though those on the right are still twice as critical of the role of journalists.

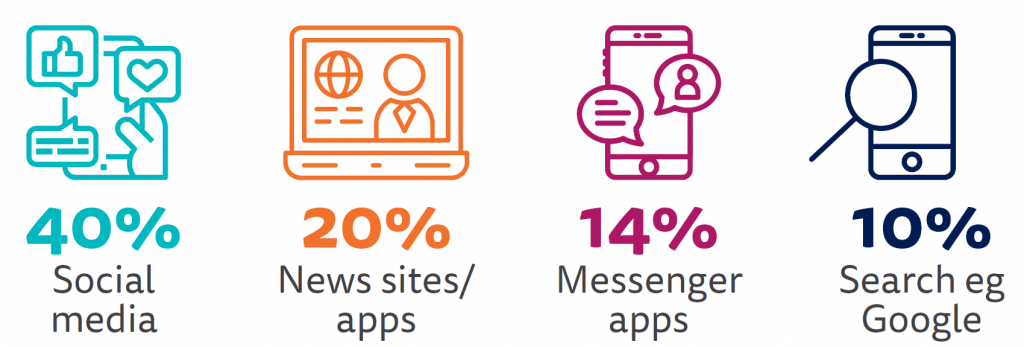

Channels of Misinformation

It is perhaps no surprise that people see social media as the biggest source of concern about misinformation (40%), well ahead of news sites (20%), messaging apps like WhatsApp (14%), and search engines such as Google (10%).

PROPORTION THAT SAY THEY ARE MOST CONCERNED ABOUT FALSE OR MISLEADING INFORMATION FROM EACH OF THE FOLLOWING

All markets

Q_FAKE_NEWS_2020c. Which of the following, if any, are you most concerned about online? False or misleading information from…

Base: Total sample = 80155

Breaking the social data down further, across all countries 29% say they are most concerned about Facebook, followed by YouTube (6%) and Twitter (5%). But in parts of the Global South, such as Brazil, people say they are more concerned about closed messaging apps like WhatsApp (35%). The same is true in Chile, Mexico, Malaysia, and Singapore. This is a particular worry because false information tends to be less visible and can be harder to counter in these private and encrypted networks. By contrast, in the Philippines (47%) and the United States (35%) the overwhelming concern is about Facebook, with other networks playing a minor role. Twitter is seen to be the biggest problem in Japan and YouTube in South Korea. Facebook is used much less widely in both of these countries.

MOST CONCERNING PLATFORM FOR FALSE AND MISLEADING INFORMATION

All markets

FAKE_NEWS_2020c. Which of the following, if any, are you most concerned about online? Please select one. False or misleading information from…

Base: Total sample in each market ≈ 2000, Taiwan = 1027.

The coronavirus crisis has reminded us that these networks can be used to spread all kinds of damaging misinformation, not just about politics. A range of unsubstantiated conspiracy theories have been doing the rounds including one linking COVID-19 to 5G networks and another suggesting that the virus was a biological weapon originating in a Chinese military research facility – though it is important to note that politicians and the media have also played a role in bringing these ideas to a wider public. In our April survey, almost four in ten (37%) said they had come across a lot or a great deal of misinformation about COVID-19 in social media like Facebook and Twitter, and 32% via messaging apps like WhatsApp.

Given these concerns, Facebook has stepped up funding for independent fact-checkers and a number of platforms including Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube have taken down misinformation that breached guidelines, including a video from Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro.6

Digital literacy has also been a priority, with a prominent link to trusted information sources pinned at the top of Facebook news feeds in many countries. Algorithms have been tweaked to prioritise official and trusted news sources.

It may be that COVID-19 finally supercharges the fight against misinformation and gives social networks more confidence to take down damaging or dubious content, but these judgements are likely to get more difficult once the immediate crisis is over, the blame game begins, and the cut and thrust of normal politics resumes.

Political Ads and Facebook

One flashpoint is likely to be the extent of any intervention by social networks in the run-up to the US presidential election in November. A burning question is the extent to which social networks should remove misleading advertising from politicians standing for election. Facebook has exempted candidates from normal fact-checking processes but has increased transparency so it is clear what campaigns are being run and how much is being spent. Twitter has taken a different view and has restricted political ads on its platform entirely.

In our January survey we find that 58% of our respondents think that misleading ads should be blocked by social media companies, with just a quarter (26%) thinking it should not be up to technology companies to decide what is true in this context. Support for blocking such ads was strongest in countries like Germany, France, and the UK where political advertising is already tightly controlled, and was weakest in countries that have traditionally worried about regulating free speech – such as the United States and the Philippines.

By contrast people are less keen on media companies omitting potentially misleading statements by candidates in the course of a campaign. Over half (52%) say that news organisations should report statements prominently because it is important to know what the politicians said. This is consistent with our earlier data which suggest the majority of people would like to make up their own mind rather than be told what to think by a journalist – or to feel that information was being withheld.

Changing Business Models and the Growth of Paid Content

It is too early to predict the full impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the news industry but it is almost certain to be a catalyst for more cost-cutting, consolidation, and even faster changes in business models. While some publications report growth in digital subscriptions, some publishers say advertising revenue has fallen by up to 50% and many newspapers have cut back or stopped printing physical copies and laid off staff.7 In Australia, News Corporation suspended print production of around 60 newspapers while, in the UK, analysts warn that as many as a third of journalists in the media could lose their job as a result of the pandemic.8 All of this puts more focus on reader payment models online – including subscription, membership, donation, and micropayment – and on the issue of trust which underpins these.

In the last 12 months more publishers have started charging for content or tightening paywalls and this is beginning to have an impact. Across countries we have seen significant increases in the percentage paying for online news, including a jump of four percentage points in the United States to 20% and eight points in Norway to 42%. We’ve also seen increases in Portugal, the Netherlands, and Argentina, with the average payment level also up in nine countries that we have been tracking since 2013.

PROPORTION THAT PAID FOR ANY ONLINE NEWS IN LAST YEAR

Selected countries

Subscription, membership, donation, or one-off payment for an article or e-edition

Q7a. Have you paid for ONLINE news content, or accessed a paid for ONLINE news service in the last year?

Base: Total sample in each market ≈ 2000.

PROPORTION THAT PAID FOR ANY ONLINE NEWS IN LAST YEAR (2014–20)

Selected countries

Q7a. Have you paid for ONLINE news content, or accessed a paid-for ONLINE news service in the last year?

Base: Total 2014–20 samples ≈ 2000. Note: 9 country average includes USA, UK, France, Spain, Italy, Germany, Denmark, Japan, and Finland.

Looking back, we can detect two clear waves of subscription growth in the United States. The first was sparked by the election of Donald Trump, with many younger and liberal voters looking to support publications that could hold the President to account. This year’s uptick may be partly driven by a new election cycle but also by publisher tactics to restrict the amount of content people can see for free combined with special deals.

In the wake of the pandemic, the New York Times and the Atlantic are among US publications reporting substantial increases in digital subscriptions while the Guardian has seen a boost to the numbers of contributors. Some publishers have emphasised the value of trusted and accurate journalism through a series of coronavirus-themed messaging campaigns designed to increase subscriptions or donations. But the crisis has also raised new dilemmas around paywalls, with many news organisations like the New York Times and El Pais in Spain dropping their paywalls for a time. Others like the Financial Times have offered a subset of content for free to ensure that critical public health content was available to all.

Many fear growing levels of information inequality, where people with less money become more dependent on social media and other low-quality news while those who can afford it get better information. Currently levels of concern about this issue from respondents are highest in the United States (24%) and Norway (17%). Lower concern in the United Kingdom (9%) may be because of widespread availability of high-quality free news from the BBC News website, many widely read popular newspapers and digital-born titles, and titles like the Guardian, with its open donation model.

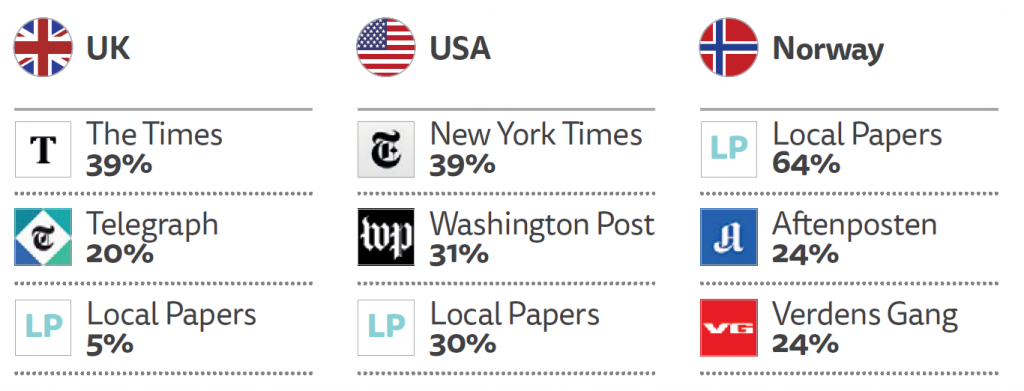

Winner-Takes-Most in Subscriptions

This year we conducted a second more detailed survey in three countries (USA, UK, and Norway) to understand more about patterns and attitudes to online news payment. This research clearly shows that a few large national news brands have been the biggest winners in all three countries. Around half of those that subscribe to any online or combined package in the United States use the New York Times or the Washington Post and a similar proportion subscribe to either The Times or the Telegraph in the UK, though in much smaller numbers. In Norway the quality newspaper Aftenposten leads the field (24% of those that pay), along with two tabloids that operate premium paywall models newspapers, VG (24%) and Dagbladet (14%). One surprise in these data is the extent to which people subscribe to local and regional newspapers online in Norway (64%). Most local news publishers in Norway charge for online news, with a total of 129 different local titles mentioned by our respondents. In the United States 30% subscribe to one or more local titles, with 131 different titles mentioned. By contrast in the UK only a handful of local publishers have put up a paywall.

PROPORTION WITH ACCESS TO PAID NEWS THAT HAVE ACCESS TO EACH BRAND

UK, USA, Norway

PAY3. You said that you currently have access to a single news brand. Please list all of the online brands you’d normally have to pay for that you currently have access to.

Base: All who have access to a single news brand: USA = 584, UK = 269, Norway = 751.

In all three countries the majority of those who pay only subscribe to one title, but in Norway more than a third (38%) have signed up for two or more – often a national title and a local newspaper. It is a similar story in the United States with 37% taking out two or more subscriptions, with additional payment often for a magazine or specialist publication such as the New Yorker, the Atlantic or The Athletic (sport). By contrast, in the UK a second or third subscription is rare, with three-quarters (74%) paying for just one title.

In the UK and Norway, three-quarters (75%) pay for subscriptions with their own money, around 5% are on a free trial, with the rest paid for by someone else (by work or a gift). The free trials seem to be twice as prevalent in the United States (10%), where competition for a limited pool of subscribers is extremely fierce.

Donations for news are relatively new, though Wikipedia and National Public Radio have generated much of their income this way for many years. Our survey showed a growing array of publications to which people are prepared to give money. In the United States 4% now say they donate money to a news organisation, 3% in Norway, and 1% in the UK. The Guardian has one of the most successful donation models of any major brand, with over a million people having contributed in the last year.9 According to our data, almost half of all the relatively small number of donations in the UK (42%) go to the Guardian, but most are one-off, with an average payment of less than £15. Other beneficiaries include small community websites such as the Bristol Cable, YouTube channels, and podcasts such as the one produced by the investigative co-operative Bellingcat.

In looking through the donation lists, it is striking to see so many political partisan websites such as The Daily Kos and Patriot Post in the US and The Canary and Novara media in the UK. In Norway, a significant number of donations to news services go to one of three far-right websites, Resett, Document, and HRS. With advertisers increasingly wary of controversial political content, donations are proving one important way to tap into the loyalty of committed partisans.

PROPORTION OF DONATORS THAT DONATE TO EACH BRAND

UK, USA, Norway

DONATE2. You say you currently donate to a news brand. Which brands do you donate to?

Base: All those who have donated: UK = 171, US = 447, Norway = 225.

After the 2008 economic crash many publishers saw advertising revenues drop by around a third and many worry that the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic could be even worse. Online subscriptions and donations may make up for some of this, especially at a time when trusted news matters more than ever, but for most publishers any extra reader revenue won’t be nearly sufficient. Industry expectations need to be realistic as many people are likely to have less disposable income and the majority of non-payers are still broadly happy with free sources.

Uncertain Future for Local News

The COVID-19 disruption is likely to hit local news providers hardest, given their continuing dependence on both print and digital advertising. Commercial local newspapers in particular are a key component of democracy in many countries, employing the majority of journalists, highlighting local issues, and holding politicians to account. In Denmark, Sweden, and some other countries the government has stepped in to provide subsidies and short-term relief for the sector.10 Without more support further closures and cuts seem inevitable. But how much would people miss their local newspapers if they were no longer there?

Our research shows that local newspapers (and their websites) are valued much more in some countries than others. Over half of those who regularly read local newspapers in federal Germany (54%) say they would miss them ‘a lot’ if they were no longer there, 49% in Norway, and 39% in the United States. By contrast only 25% of those who regularly read newspapers in the UK, 18% in Argentina, and 13% in Taiwan say the same. The value placed on local news seems to be partly related to the importance that countries place on their regions more generally – and the extent to which local politics matters. In federated systems like Germany and the United States local newspapers play a critical role in providing accountability and this is reflected in these scores. The value that people place on their local newspaper is closely correlated with the higher subscription and donation rates that we see for local news in Norway and the United States when compared to the UK.

PROPORTION OF READERS WHO WOULD MISS THEIR LOCAL NEWSPAPER A LOT

Selected countries

L4_2020. How much would you miss your local newspaper/website if it went out of business? Showing code ‘a lot’.

Base: Those who consume local newspapers in last week. Germany = 1136, Norway = 1283, USA = 730, UK = 835.

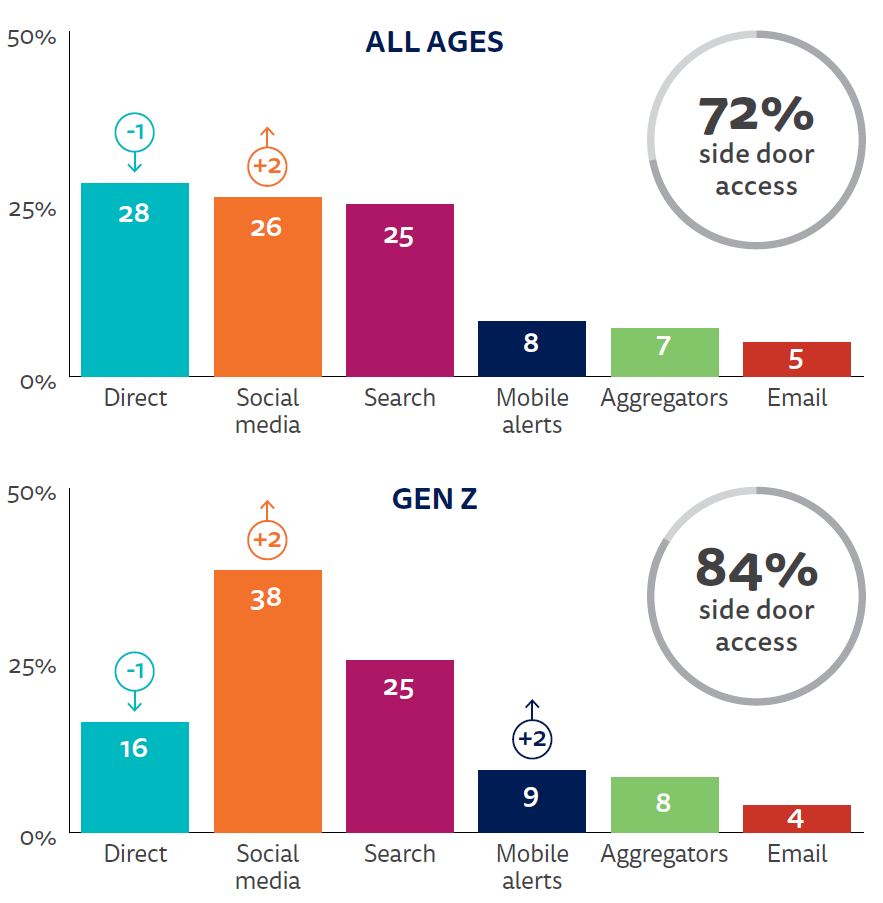

Gateways and Intermediaries

In terms of access points for online news, habits continue to become more distributed – as more and more people embrace various digital platforms that were initially used most intensely by younger people. Across all countries, just over a quarter (28%) prefer to start their news journeys with a website or app, followed by social media (26%) – up two percentage points on last year. Once again, though, we see very different patterns with 18–24s, the so-called Generation Z. This group has a much weaker direct connection with news brands (16%) and is almost twice as likely to prefer to access news via social media (38%).

If younger groups cannot be persuaded to come to specific websites and apps, publishers may need to focus more on how to build audiences through third-party platforms like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Snapchat. This may become more attractive for publishers now Facebook has started to offer direct payments for its dedicated ‘news tab’, but aggregated environments have not yet proved a good environment to build the loyalty and attribution that will be needed for long-term relationships.

MAIN GATEWAYS TO NEWS

All markets

Q10a. Which of these was the MAIN way in which you came across news in the last week?

Base: All/18-24s that came across online news in the last week: All markets = 74181/8640.

Mobile Aggregators

Some publishers have been reporting significant increases in referrals from mobile apps such as Apple News, Upday, and various Google products including Google News and Google Discover. Some of these (Apple News and Google) are very hard to measure in surveys because respondents often cannot recall these services – especially if they access via a notification. Apple News is still only available in a few countries but is accessed by 29% of iPhone users in the United States and 22% in the UK. Our data suggest that the premium Apple News + ($9.99 a month) has not yet has much impact outside the US, where the service includes content from the Wall Street Journal and the Los Angeles Times.

Aggregators remain more important in some countries (South Korea, Japan) than others but overall access remains constant at around 7% and there has been little movement in the headline numbers for specific apps. Line News reaches 22% and Gunosy 12% in Japan each week, while Kakao Channel (25%) is a popular mobile aggregator in South Korea. TopBuzz, an artificial intelligence (AI) driven aggregator that often surfaced poor quality news is being closed down after attracting low levels of usage in western countries, though it was becoming popular in parts of the Global South such as the Philippines (9%), Kenya (11%), and Brazil (9%).

Publishers Fight Back with Email and Other Loyalty Tactics

Faced with the growing power of platforms, publishers have been working hard to build direct connections with consumers via email, mobile alerts, and podcasts. Across countries, around one in six (16%) access news each week via email, with most of these (60%) accessing a briefing of general or political news, often sent in the morning. But publishers have been extending the range of formats, increasingly offering ‘pop up emails’ on subjects like coronavirus and the 2020 presidential elections. Emails have proved effective in attracting potential new subscribers, as well as encouraging existing users to come back more frequently.

Despite this revival in the newsletter format we find surprising differences in the level of adoption across countries. In the United States one in five (21%) access a news email weekly, and for almost half of these it is their primary way of accessing news. Northern European countries have been much slower to adopt email news channels, with only 10% using email news in Finland and 9% in the UK.

The New York Times now offers almost 70 different scheduled emails, with the popular morning briefing now reaching 17 million subscribers. The size and importance of this audience has meant an increased profile for flagship emails, with senior journalists appointed as hosts to help guide users through the news each day.11

Americans get, on average, more emails from different news providers (4) compared with Australians (3) or British (3). Across countries almost half (44%) say they read most of their news emails. Emails tend to be most popular with older age groups, while mobile notifications are more popular with the young and continue to grow in many countries.

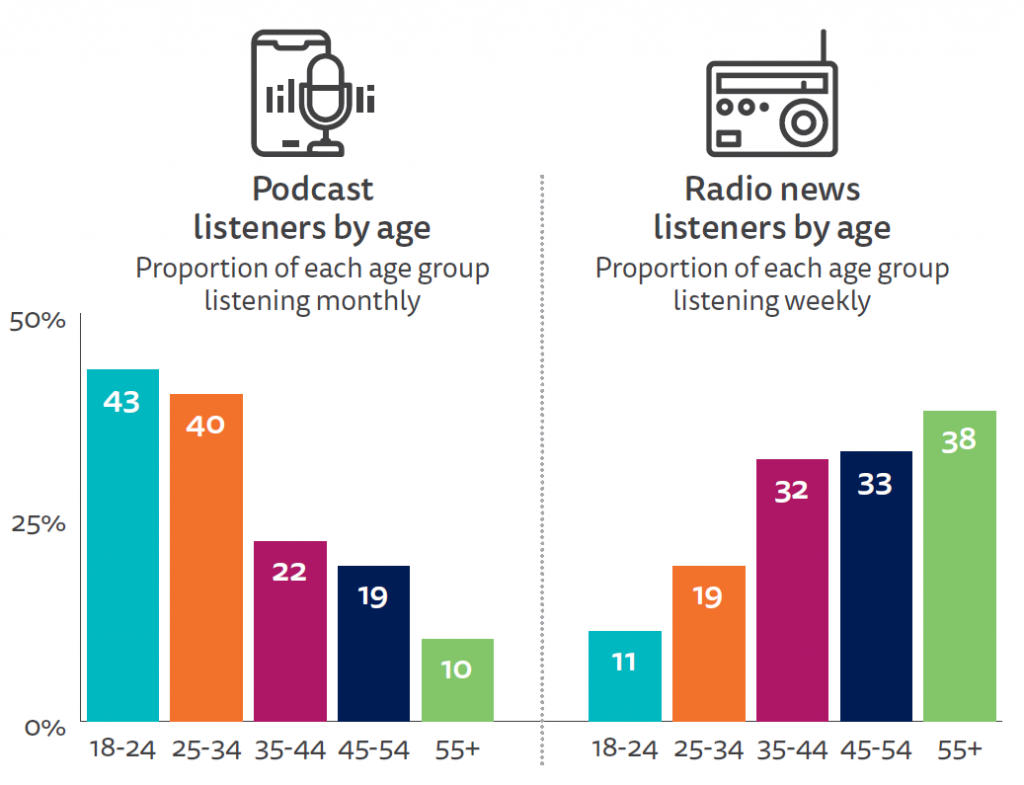

Podcasts and the Rise of Audio

In the last few years podcasts have become another important channel for driving loyalty to specific news brands. The Daily from the New York Times attracts 2 million listeners a day and, although the advertising revenue is substantial, the main strategic aim is to attract new subscribers and to build habit with existing ones (Newman and Gallo 2019). The Guardian (UK), Aftenposten (Norway), and Les Echos (France) are amongst publishers to have launched successful daily news podcasts in the last two years. During the coronavirus lockdowns some podcast listening reportedly fell by up to 20% – a reminder of how integral podcasts have become to commuting habits and other activities outside the home.12 At the same time, listening to other types of podcasting has shifted to the home and there have been some breakout hits, including Das Coronavirus-Update, a 30-minute show featuring one of Germany’s top virologists, which reached No. 1 in the podcast charts there.

The underlying picture remains one of growth. Our data show an overall rise in podcast listening to 31% (+3) across a basket of 20 countries we have been tracking since 2018. Almost four in ten access monthly in Spain (41%), Ireland (40%), Sweden (36%), Norway (36%), and the United States (36%). By contrast usage in the Netherlands (26%), Germany (24%), and the UK (22%) is nearer to a quarter.

PROPORTION THAT USED A PODCAST IN THE LAST MONTH

Selected countries

Q11F. A podcast is an episodic series of digital audio files, which you can download, subscribe, or listen to. Which of the following types of podcast have you listened to in the last month? Please select all that apply.

Base: Total sample in each market ≈ 2000. Note: We excluded markets with more urban samples as well as those where we are not confident that podcasts is a term sufficiently well understood to produce reliable data.

Podcast listeners tend to be younger (see next chart) and mainly listen via headphones/mobile phones. These demographics and habits are not just of interest to subscription businesses but also to broadcasters who, as we’ve already noted, are finding it harder to reach under-35s through linear programming. In the UK half of all podcasts are listened to by under-35s, despite these making up just a third of our sample. By contrast, the majority of those listening to traditional news bulletins and programmes on the radio each week are over 50.

PROPORTION THAT USED A PODCAST IN THE LAST MONTH BY AGE

United Kingdom

Q11F. A podcast is an episodic series of digital audio files, which you can download, subscribe, or listen to. Which of the following types of podcast have you listened to in the last month? Q3. Which, if any, of the following have you used in the last week as a source of news?

Base: 18–24 = 236, 25–34 = 287, 35–44 = 350, 45–54 = 353, 55+ = 785.

Many podcasts contain an informational element (sport, lifestyle, true crime) but podcasts specifically about news and politics are amongst the most widely listened to. About half of podcast users listen to a news podcast in the US, where the market has developed furthest. Podcast users in the United States say that the format gives greater depth and understanding of complex issues (59%) and a wider range of perspectives (57%) than other types of media.

News podcasts are most popular with 25–34s (young millennials). Those aged 18–24 are less likely to listen to news podcast but are some of the heaviest consumers of lifestyle and celebrity podcasts as well as true crime.

The deep connection that many podcasts seem to create could be opening up opportunities for paid podcasts, alongside advertising-driven models. Almost four in ten Australians (39%) said they would be prepared to pay for podcasts they liked, 38% in the United States, and a similar number in Canada (37%). Willingness to pay was lower in Sweden (24%) and the UK (21%) where so many popular podcasts come from free-to-air public broadcasters.

Which Platforms Do People Use to Access Podcasts?

Podcasts have traditionally been associated with Apple devices, but that is changing rapidly. In the last 18 months Spotify has invested over $500m in podcasting and has reported a doubling of podcast listens.13 Broadcaster apps like BBC Sounds, ABC Listen (Australia), NPR One (USA), and SR Play (Sweden) now offer original podcasts in addition to live and catch-up radio. Google has started to promote podcasts within search and has revamped its own podcast service. Our data from the UK show BBC Sounds (28%) at a similar level to Apple podcasts (26%) and Spotify (24%) in terms of access, while Spotify (25%) is now ahead of Apple (20%) and Google (16%) in the United States. The US has a much larger ecosystem of widely used smaller podcast apps and services including TuneIn, Podcast Addict, and Stitcher. Spotify (40%) is ahead in Sweden, the country of its birth and also in Australia (33%). In Sweden the national radio broadcaster reaches more than a quarter of podcast users.

Spotify’s move into podcasts, which includes commissioning its own high-quality original content, is bringing audio programming to a wider and more mainstream audience but it is also raising new questions for public broadcasters. Many worry that aggregators will take much of the credit/attribution for public content and are building up their own platforms instead. Some are withholding content from Spotify and Google or are previewing it first in their own apps. Broadcasters have also been losing presentation and production talent to newspaper groups, platforms, and independent studios.

Has Reading Had its Day Online?

For many years bandwidth and technical limitations meant online news was largely restricted to text and pictures. But now, in most parts of the world, it is possible to seamlessly watch news videos or listen to on-demand audio as well. But what do consumers prefer? Reading text is convenient, but can be difficult on small smartphone screens, and a desire to get away from screens may be one factor driving the current boom in audio listening, according to research (Newman 2018).

We find that, on average, across all countries, people still prefer reading news online, but a significant proportion now say they prefer to watch, with around one in ten preferring to listen. Parts of the world with strong reading traditions such as Northern Europe are most keen on text (54%), while our sample of Asian markets is more equally split (44% for text and 42% for video). The Philippines and Hong Kong are two markets where a majority say they prefer to watch news online rather than read (55% and 52% respectively). Across markets we also find that people with lower levels of education are more likely to want to watch online news, compared with the better educated– a finding which reflects traditional offline preferences around television and print.

Perhaps more surprisingly, we find that in a number of countries including the UK, Australia, France, and South Korea, younger people (under-35s) are more likely to say they prefer to read rather than watch news online. We know that the young consume more video news than older people because they are more exposed via Facebook and YouTube, but the speed and control that comes though reading often seems to trump this when it comes to underlying preference.

Video Consumption across Countries

Looking at absolute consumption of different kinds of video news we also see interesting regional differences in line with these stated preferences. Nine in ten say they access video news online weekly in Turkey (95%), Kenya (93%), the Philippines (89%), and Hong Kong (89%), but only around half this proportion do in Northern European countries such as Germany (43%), Denmark (41%), and the UK (39%).

Across countries over half (52%) access video news via a third-party platform each week, such as YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter, with a third (33%) accessing via news websites and apps. But again, we find very significant differences between markets. In Hong Kong three-quarters (76%) access video news via third-party platforms but this figure is less than a quarter (23%) in the UK.

The popularity of social networks and video platforms in Asia, Latin America, and Africa seems to be stimulating video consumption at the expense of text – even if most people consume a mix of the two.

Even in Europe a number of publishers have stepped up investment in video formats. The German public broadcaster ARD has recently made vertical video a central feature of its Tagesschau app. Swiss publisher Ringier has launched Blick TV, a 15-minute news show that is broadcast online but updated through the day, while rival 20 Minuten is significantly increasing its video production. The big dilemma for publishers, however, is how to monetise video, which has proved difficult for shorter news items. Publishers like the New York Times, Vox, and BuzzFeed have been focusing on longer form linear commissions aimed at online streaming services and cable TV.

Consumer preferences around video and audio are changing, opening up new possibilities for publishers, but shifting resources from text carries significant risks while the commercial returns are still far from proven.

Social Media Preferences Also Becoming More Visual

With video now a key component of social platforms, it is interesting to see how this is playing out in the networks people use most often.

Each year we track the importance of different social networks averaged across more than a dozen countries we have been tracking since 2014. Facebook and YouTube remain by far the most important networks, with around two-thirds using them each week for any purpose. Almost half now use WhatsApp (48%), part of a shift towards more private messaging which started in around 2016.

Another big change in the last few years has been the growth of Instagram which popularised visual formats like ‘stories’ and short videos via IGTV. Instagram now reaches more than a third (36%) weekly and two-thirds of under-25s (64%). As people spend more time with the network, the role of news has also increased significantly. Instagram reaches 11% across age groups, almost as many as use Twitter for news.

Both Instagram and WhatsApp were designed from the ground up for mobile usage, which gives them a cutting edge with younger people. In developing countries, Facebook has often made arrangements to bundle these applications with free data which has also helped them grow. After years of stagnation, Twitter has also seen significant growth in a small number of countries, also driven by younger demographics engaging with the platform more often. Twitter has also been pushing new video formats and monetisation of live video in the last few years.

By allowing Instagram and WhatsApp to develop separately, Facebook as a company has been able to cater for many different demographics and try new formats, without losing its core loyalists. Across countries, Facebook Inc now reaches 85% each week on average, rising to 94% in Brazil and 96% in Kenya and South Africa.

Dependence on Smartphones Continues to Grow

Over two-thirds (69%) of people now use the smartphone for news weekly and, as we’ve seen, these devices are encouraging the growth of shorter video content via third-party platforms as well as audio content like podcasts. Those who use smartphones as a main device for news are significantly more likely to access news via social networks.

Usage is often highest in parts of the Global South such as Kenya (83%) and South Africa (82%) where fixed-line internet tends to be less prevalent. Access is lowest in Canada (55%), Japan (52%), and in much of Eastern Europe, though even here the smartphone has become – or is on its way to becoming – the main platform for accessing news.

Across countries almost half (48%) use two or more devices to access news each week compared with 39% in 2014. Computers and laptops remain important for many but the convenience and versatility of the smartphone continues to win out. In the UK the smartphone overtook the computer in 2017 and is now used by around two-thirds of our sample. Tablets are flat in terms of usage for news (26%) with a small group of older and richer users continuing to value their larger screens. Smart speakers are now used for news by around 5% of online users.

AI-driven smart speakers such as the Amazon Echo and Google Home continue to become more widely available, along with the intelligent assistants inside them, now in more than 20 countries including India, Mexico, and a wider range of European languages. Usage for any purpose is up five percentage points to 19% in the UK and a similar amount in Germany to 12%. In South Korea, where local firms make a range of popular speakers including the Naver Wave and Kakao Mini, usage is up four points to 13%.

Both Amazon and Google have been looking to improve the news experience after disappointing levels of take-up of available for on-demand briefings. Google has been rolling out a new atomised audio news service that aims to offer a more story-based approach and the BBC has added more controls to its news briefing allowing consumers to skip between stories. Despite these initiatives, our data suggest that only between a third and a quarter are using their devices to regularly access news.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 lockdown has reminded us both of the value of media that bring us together, as well as the power of digital networks that connect us to those we know and love personally. For many of those stuck at home, television remains a window to the wider world, and some broadcasters have provided a platform for governments and health authorities to communicate health and other advice to mass audiences.

New digital behaviours have also emerged in this crisis that are likely to have long-term implications. Many have joined Facebook or WhatsApp groups for the first time and have engaged in local groups. Young people have consumed more news through services like Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok. Video conferencing has emerged as a new platform for personal communication but has also changed the face of government press conferences. The media have embraced these new technologies in terms of remote working, but also in terms of the production and distribution of content.

The biggest impact of the virus is likely to be economic, with local and national media already cutting staff or publishing less frequently. The coronavirus crisis is driving a cyclical downturn in the economy hurting every publisher, especially those based on advertising, and likely to further accelerate existing structural changes to a more digital media environment in terms of audience behaviour, advertising spending, and reader revenues. Reader payment alternatives such as subscription, membership, and donations will move centre stage, but as our research shows, this is likely to benefit a relatively small number of highly trusted national titles as well as smaller niche and partisan media brands. The crisis in local media will become more acute with more calls for support from government and technology companies – with all the problems that this entails in terms of media independence.

As if this were not enough, dependence on aggregated and mobile content has made it harder for news brands to forge direct relationships with consumers. Our report shows that younger users, especially those now coming into adulthood, are even less connected with news brands and more dependent on social media. More effective distribution of formats like video, podcasts, emails, and notifications may help but most publishers continue to struggle to engage more deeply with the next generation and other hard-to-reach groups. More widely, concern about misinformation remains high, while trust in the news continues to fall in many countries.

Despite this, there are some signs of hope. The COVID-19 crisis has clearly demonstrated the value of reliable trusted news to the public but also to policymakers, technology companies, and others who could potentially act to support independent news media. The creativity of journalists has also come to the fore in finding flexible ways to produce the news under extremely difficult circumstances. Fact-checking has become even more central to newsroom operations, boosting digital literacy more widely and helping to counter the many conspiracy theories swirling on social media and elsewhere. Publishers have also found innovative ways to display and interrogate data, just one of many format innovations that have helped audiences understand the background and the implications for each individual.

The next 12 months will be critical in shaping the future of the news industry. Many news organisations go into this period clearer than ever about the value of their product even if the immediate outlook looks uncertain.

- https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2020/mar/24/boris-johnsons-covid-19-address-is-one-of-most-watched-tv-programmes-ever ↩

- https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/tv-radio/2020/03/coronavirus-bbc-corporation-boris-johnson-protect. EBU Report, Covid-19: The Impact on Digital Media Consumption, Apr. 2020, https://www.ebu.ch/publications. ↩

- https://www.niemanlab.org/2020/04/the-coronavirus-traffic-bump-to-news-sites-is-pretty-much-over-already ↩

- https://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/listeningpost/2019/11/chile-protests-media-191103105957626.html ↩

- New York Times analysis of traffic changes https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/07/technology/coronavirus-internet-use.html ↩

- https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-brazil-president-refuses-to-ramp-up-covid-19-lockdown-as-facebook-pulls-video-11966279 ↩

- https://www.poynter.org/business-work/2020/a-qa-with-tampa-bay-times-chairman-and-ceo-paul-tash-about-the-times-print-reduction ↩

- https://www.endersanalysis.com/reports/enders-analysis-calls-government-support-news-magazine-media ↩

- 1.16m have contributed, including 821,000 ongoing monthly donations (and subscriptions). https://www.theguardian.com/media/2020/apr/29/guardian-reports-surge-in-readers-support-over-past-year ↩

- https://euobserver.com/coronavirus/147956 ↩

- https://www.niemanlab.org/2020/04/the-new-york-times-morning-email-newsletter-is-getting-an-official-host-and-anchor ↩

- https://podnews.net/article/coronavirus-covid19-affecting-podcasting ↩

- https://www.theverge.com/2020/2/5/21123905/spotify-earnings-q4-2020-podcasting-investment-operating-loss ↩