Executive Summary

In this report, we analyse how local and regional newspapers in Europe are adapting to an increasingly digital, mobile, and platform-dominated media environment. Local news organisations play a particularly important role in terms of serving their communities. The challenges and opportunities they face are partly similar to those of national news organisations (declining legacy reach and revenues, shrinking newsrooms, new chances to connect with audiences online) but also partly distinct (most have fewer opportunities to pursue scale and more limited resources to invest in digital media but also less direct competition in their local markets).

We focus here on the digital transition of local and regional newspapers and how they define and navigate the challenges and opportunities they face, including creating digital-first newsrooms, understanding and adapting to audience needs, and diversifying their business models. A key theme is how the approaches of local newspapers’ parent companies shape the ways they adapt to digital media.

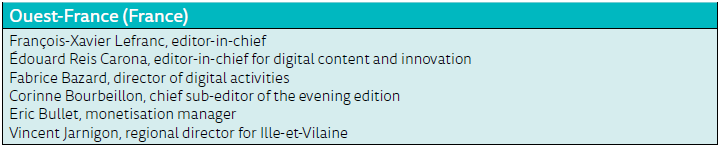

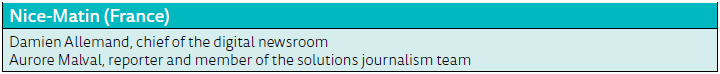

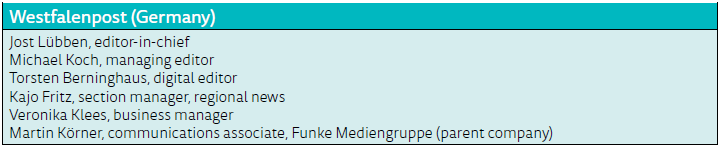

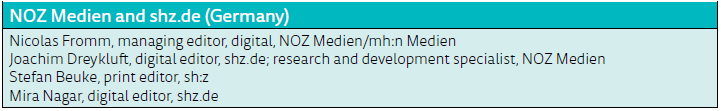

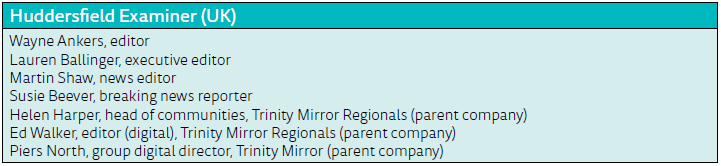

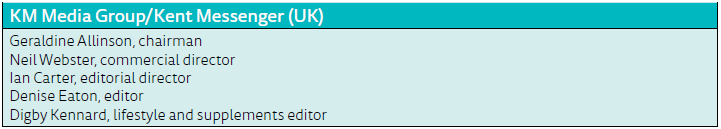

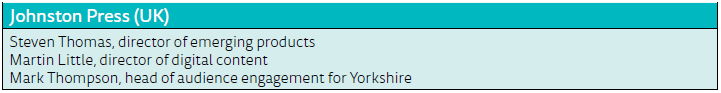

The report is based on 48 interviews with editors, reporters, and commercial directors at newspapers and editorial and commercial executives at their parent companies in the UK, France, Germany, and Finland. Our case newspapers represent both independent and group-owned ownership models.

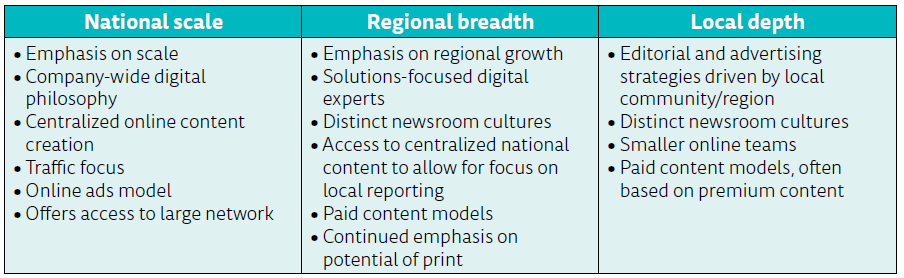

In particular, we suggest that parent companies are pursuing different overall strategies for producing and monetising local news in the digital age. We identify three approaches: the search for national scale, regional breadth, or local depth. These strategies influence not only how local newsrooms make decisions about editorial content but also how they differentiate their online and print products, discuss their audiences, cultivate social media tactics, focus their business models, and develop plans for the future.

(1) National scale: This strategy emphasises economies of scale, pursued through the acquisition of a portfolio of different titles that, in aggregate, can draw the largest possible audience, which is in turn primarily monetised through advertising. This approach was most evident among the national parent companies in the sample, particularly in the UK. These companies tend to feature centralised newsrooms producing online content that can then be shared across multiple newspapers and adapted to local markets. They also seek to minimise costs through shared digital advertising sales, human resources, etc. These companies pursue a common digital culture across their holdings through in-newsroom training, conference calls, and company-wide editorial initiatives. Interviewees discussed both the benefits of this structure (access to digital experts and tools, a large network of local newspapers, robust web content) and challenges (what some saw as difficult-to-meet traffic targets).

(2) Regional breadth: This approach also emphasises economies of scale but focuses on developing a more focused portfolio of editorial and other offers for a particular, often contiguous, region. The aim is to achieve a strong and distinct market position in that specific area, a position that local publishers increasingly seek to monetise through paid content models and the pursuit of auxiliary forms of revenue from events, services, e-commerce, and the like to supplement advertising. This approach is evident in large regional companies in France, Germany, and Finland, countries that have long sustained a robust local and regional press. As in the national-scale approach, these organisations often feature centralised newsrooms for national content while emphasising regionalism in editorial content and considerable centralisation of back-end functions, such as ad sales and human resources. However, companies focused on building a broad range of offers tailored to the different communities in the region they serve often give local titles autonomy to address specific needs, and affiliated newspapers maintain distinct cultures.

(3) Local depth: This approach is pursued by individual local titles and groups and by those owned by smaller parent companies. Examples include Finland’s Kaleva, France’s Nice-Matin, Germany’s Main-Post, and the UK’s Kent Messenger. These organisations remain editorially and financially powered by their communities and regions – reporting on smaller geographic areas and in many cases relying on local advertising and print subscriptions. Like larger groups pursuing regional breadth, they increasingly look beyond display advertising and seek to sustain themselves through premium content and subscription models as well as auxiliary revenue sources. These organisations are often highly tailored to the specific areas they serve but tend to have fewer resources and hence less complex infrastructures for digital production than other companies in the sample. Their emphasis on a more targeted geographic area and audience also make them less able to realise economies of scale and more dependent on local support in the long run.

All of these approaches are distinct from a more resigned strategy that is seen in some parts of the local and regional news industry, where companies focus on cutting costs to remain profitable even as legacy revenues decline. All of the approaches discussed here involve investment in developing new digital offerings and ways of engaging local communities that are not solely focused on extracting short-term operating profits from a declining print business.

This orientation toward the future is critically important for the future of local news, both as a business and as a part of local communities. Most of the local news organisations we cover here still generate 80–90% of their revenues – and sometimes more – from legacy print operations that are in clear structural decline. Although many of them are building impressive new digital offerings, across their websites, social media accounts, and other channels, they have significantly lower reach among younger people in their communities than they have had historically among their older print readers. Like many other news organisations, they find themselves in a position where some of the companies with whom they compete for advertising revenues – large platform companies like Facebook and Google – are also central to how they reach their online audiences through search engines and social media.

The traditional bundle of local news combined with other information about the weather, movie listings, sports results, and various forms of advertising is less attractive to younger users, and many interviewees believe that the classic combination of a traditional package overwhelmingly funded through advertising will not remain the mainstay of local journalism. Their commitment to continued experimentation is based on their recognition of the pressing need to continue to evolve the ways they serve their local communities through their journalism, as well as the digital business models that enable this aim. For all the impressive work already done, the digital transition of local news is still clearly at an early stage.

Introduction

Local news plays a vital role in democratic societies. Local news organisations, from legacy players such as newspapers and TV and radio stations to emerging actors such as hyperlocal news websites, have a distinctive ability to connect and empower their audiences through informing them about their communities and equipping them with the information they need to become active participants (Harte et al. 2017; Nygren et al. 2017). Local newspapers, in particular, have long occupied dominant positions in their media environments, facing little competition – for readers or advertisers – and in many cases offering information not available anywhere else (Nielsen 2015b).

The future of local media, however, has become increasingly uncertain, with the shift to a digital-, mobile-, and platform-dominated media environment and the resulting changes in audience behaviour affecting this sector perhaps even more acutely than national and international media (Ali and Radcliffe 2017; Cornia et al. 2016, 2017; Newman et al. 2017; Sehl et al. 2016, 2017). Historically, advertising was the most important source of revenue for many local newspapers, and because they were the main publication available in their communities, they had considerable market power and could operate sometimes very profitable businesses. The move to digital media has changed this status profoundly. Advertisers increasingly invest in online advertising, which is dominated by large US-based platform companies that offer low prices, precise targeting, and unduplicated reach. Local newspapers cannot compete directly, and online, their traditional business model, advertising, is thus existentially challenged. As one advertising executive put it: ‘Local isn’t valuable anymore. Anyone can sell local’ (quoted in Nielsen 2015a).

The need for local news organisations, particularly newspapers, to adapt to these trends and demonstrate their relevance while facing declining advertising revenues, circulation rates, and staff sizes has resulted in a perfect storm for layoffs, buyouts, and even closures. In this report, we look at how eight European local and regional newspapers operating in different countries are adapting to these shifts and evolving both their editorial offerings and the business that underpins it.

Despite their shared emphasis on uniting diverse audiences in specific geographic areas (Powers et al. 2015) and generally strong sense of democratic purpose to provide analysis and accountability (Coleman et al. 2016), local media should not be regarded as monolithic. Understanding the outlook for local news requires considering both variations among and within countries, such as assessing differences in media systems and between rural and urban news organisations (Nielsen 2015a). Across Europe, local media environments feature significant differences, with strong public- and private-sector national news but a heavily consolidated local press in the UK, market-dominant regional newspaper companies in France, and robust local and regional newspapers in Germany and the Nordic countries. Therefore, comparatively evaluating local media is vital.

This report examines challenges and opportunities facing European local newspapers and how they have responded to shifts in audience preferences, revenue opportunities, and ownership requirements. In particular, the report addresses three components of local news: editorial strategies, including the routines and processes through which journalists at local newspapers produce news; distribution strategies, specifically how expectations have changed in response to the need to deliver news on digital platforms and via mobile in particular; and business strategies, including both existing and emerging revenue sources.

This research is based on 48 interviews conducted between November 2017 and February 2018 with managers, editors, reporters, and business staff members at local and regional newspapers and their parent companies in four countries. The countries selected – Finland, France, Germany, and the UK – represent different media systems (Hallin and Mancini 2004), and the chosen newspapers operate according to different ownership models.

We chose two similar-sized local or regional newspapers in each of the countries: the Huddersfield Examiner and the Kent Messenger (UK), Kaleva and Etelä-Suomen Sanomat (Finland), Westfalenpost and Main-Post (Germany), and Ouest-France and Nice-Matin (France). We also interviewed representatives from the newspapers’ parent companies (Trinity Mirror for the Huddersfield Examiner, Keskisuomalainen for Etelä-Suomen Sanomat, and Funke Mediengruppe for Westfalenpost). Two of the newspapers, Kent Messenger (KM Media Group) and Main-Post, are part of family-owned regional companies. We interviewed representatives from other local and regional news companies in the countries as well: NOZ Medien in Germany and Johnston Press in the UK. The majority (41) of the interviews were conducted in person, while the remaining interviews were conducted over the phone or via Skype. See the appendix for a complete list of interviewees.

We aimed to interview staff members at multiple levels of the newspapers in the sample, including editors responsible for developing and implementing their organisations’ editorial and digital strategies, as well as editors and reporters who report local news. We also interviewed business staff members to better understand how commercial practices are changing in the digital environment as well as executives involved with developing editorial, production, and commercial strategies at the company level, particularly for digital news.

This report thus takes a broad look at the practices and perspectives of local and regional news organisations. We found that organisations, across their different starting points and the contexts in which they operate, face similar challenges, including shrinking circulations and advertising revenues for their print publications and enhanced pressure to respond to digital shifts through reorganising their editorial production processes and investing in digital media, such as websites, digital editions, apps, video, and social platforms. The ways they approach these changes, however, have taken different forms – we identify the search for national scale, the pursuit of regional breadth, and the aim of local depth as three strategies.

The first two approaches aim to realise economies of scale but potentially risk titles becoming ‘local in name only’, whereas localisation ties a title tightly to its local community but may result in difficulty maintaining a sustainable business. All the titles covered still generate a large majority of their revenues from print, but circulation continues to decline and the readership is ageing, so developing new digital offerings is critical both from a business point of view and for the newspapers to continue serving their communities. Even the most successful local titles will likely have to continue to cut their costs as legacy revenues decline and digital revenues and auxiliary sources of revenues, such as events and e-commerce, are unlikely to compensate for revenues fundamentally premised on a form of market power that even the most popular and innovative local news organisations simply no longer have. That said, the impressive new initiatives launched by many of the organisations covered here, as well as their commitment to continued investment in both their core editorial mission as well as new experiments with digital media, show how committed they are to the digital transition of local news.

This report is structured as follows. First, we assess the interviewees’ perspectives on the most significant challenges and opportunities facing their organisations. We then examine efforts to streamline editorial, digital, and commercial strategies across the news companies. We also address how the newspapers implement digital-first cultures, as well as how they use social media and reach audiences in innovative ways. We then consider efforts to diversify the newspapers’ business models. Lastly, we assess how the functions of local media are changing in the digital news environment and conclude with a summary of the findings.

1. Local News and Digital Media

Like their national and international counterparts in the private sector, local newspapers continuously work to adapt their editorial and business models to remain relevant and financially viable in the digital media environment. Newspapers around Europe have seen declining print revenues, and although leading newspapers have invested significantly in digital offerings, the gains they achieve often fail to compensate for print losses (Cornia et al. 2016).

Among local and regional newspapers, these efforts are evident in the ways interviewees described the most significant challenges and opportunities facing their organisations. Their responses reflect issues facing news media organisations around the world – from monetising digital content and increasing online subscriptions to drawing younger readers to the influence of Google and Facebook on online traffic (Newman et al. 2017) – and concerns specific to the local sector.

Staff members with nearly all of the newspapers in the sample noted that they have faced declining circulation numbers and advertising revenues, particularly for print, and they have struggled to find ways to attract new (in many cases, younger) readers in an increasingly crowded digital media environment as well as to monetise online content and traffic.

Édouard Reis Carona, editor-in-chief for digital content and innovation at Ouest-France, said the company has lost 25% of its print advertising revenues in less than ten years and, as a result, is shifting its focus to creating loyal online readers who are willing to pay for local content and become subscribers for both print and digital products.1

Other newspapers, such as the Huddersfield Examiner, focus on ‘turning page views into revenue and income’, as news editor Martin Shaw described.2 Lauren Ballinger, executive editor of the Huddersfield Examiner, said one reader recently complained that the newspaper is focused on ‘clickbait’ to increase web traffic rather than providing information.

I said, ‘Well, we’re a business. We’re trying to keep the Examiner going for future generations, and the only way we can do that, because people aren’t buying as many papers anymore, is getting people on our website.’ I mean, he’s somebody who clearly just wants his news for free. He doesn’t want to come to the website; he just wants to be told this stuff and feels an entitlement to that information.3

For NOZ Medien in Germany, editorial operations continue to be subsidised by print. However, the company has accumulated ‘a huge pile of content and a huge pile of local and regional content’, which distinguishes it from national players like Spiegel Online, according to Joachim Dreykluft, a research and development specialist for NOZ Medien and digital editor for shz.de. As a result, ‘The biggest task is to invent things that will be able to establish an independent digital journalism.’4

Teppo Koskinen writes for a special Sunday section of Etelä-Suomen Sanomat called Sunnuntaisuomalainen, which is shared among four newspapers throughout the region. He said a primary obstacle is convincing potential audiences that the newspaper offers stories that ‘they feel are relevant to their everyday lives. … Content that they feel the need to pay for’.5

This task can be particularly difficult in the case of younger readers, who have access to multiple information channels and are increasingly intolerant of some forms of digital advertising. As Kirsi Hakaniemi, head of digital business for Keskisuomalainen, described:

Are they still interested in local life? We assume that when you start a family and go to a job and buy a house, the local life becomes more interesting, too. … We have to follow the reader and the user, we have to serve them content, whatever it is that they want, and we have to serve it wherever and in whatever device they want to use it.6

Kajo Fritz, a section manager for regional news at Westfalenpost, described a need to ‘find new ways of journalism that fit perfectly to the wishes of our readers’, including podcasts, videos, and other multimedia approaches. He added:

We have to get new readers or younger people, and we have to be stronger. We must do this kind of journalism. It’s not enough only to print articles like for the last 70 years.7

Mira Nagar, a digital editor with shz.de, said that although her organisation works to meet the demands of online readers, such as by continually posting new content and connecting with them via WhatsApp newsletters, she does not want to neglect print customers.

The challenge is to keep pace while not losing those older generations or traditional people … who read our news on paper the next day or the day after it happens.8

Jarkko Haukilahti, regional manager for Etelä-Suomen Sanomat, said his organisation has raised subscription prices to counter declining advertising revenues, which prices out some of its older readers, a historically loyal demographic who may live alone or have low pensions.9

Trinity Mirror, the biggest regional media company in the UK, with more than 110 regional newspapers, has built audience scale, but, according to Ed Walker, editor (digital) for Trinity Mirror Regionals, the company must focus on better understanding and engaging its audience, such as by increasing diversity within its social media followings and reaching specific groups and communities. He said one of the company’s biggest opportunities is video.

We’re seeing some real successes in creating native video because we have unique stories and unique content, which is a huge diversifier on social media. We cover specific geographies, so no one else is making that content.10

Piers North, group digital director for Trinity Mirror, put it this way: ‘In digital, you need to be either very, very big or very, very niche.’11

The interviewees also recognised the risks of relying on third-party platforms, such as Facebook. As Mark Thompson, head of audience engagement for Yorkshire for Johnston Press, described:

There is no guarantee, there is no contract there; they can tweak the algorithms without telling us. … I think the opportunity also is finding new channels, finding a new way to reach people, so we are going much harder on newsletters, more web apps, groups. We need to have a bit more diversity in regards to how we get our content out.12

Similarly, Steven Thomas, director of emerging products for Johnston Press, said his company’s focus should be less on driving scale and more on ‘creating content that readers will connect to and, ideally, pay for’.

Now that may well be multiple niche products that talk to a particular subject or have a particular geographic code or angle, but we need to have the patience to support gradually moving towards a combination of free-to-view and paid models. [ … ] We’re a newspaper business adapting well to the digital challenge. We still make the majority of our revenue from newspaper sales, but digital revenue is continuing to increase. You have to keep the quality up, and you also have to accept you cannot only work within the constraints of your current product suite.13

In addition to convincing readers of the value of investing in digital content, interviewees also said they have faced challenges in convincing their newsrooms that online content is as valuable as print. This task can be particularly difficult in that most newspapers are not increasing staff sizes to accommodate the enhanced workload of a 24-hour online news cycle. Even so, they expressed that in the ever-changing digital environment, the need to adapt to new trends and audience preferences is vital.

Julia Back, an editor at Main-Post, said that because print remains the primary revenue source, convincing staff members to conform to a digital-first focus is difficult.

It’s one thing our readers are not used to, to pay for something online. But also the journalists are not used to it, to concentrate online. It’s a generation thing. Especially the older colleagues sometimes find it hard to think online first, or mobile first. Print is everything for them, and it’s hard to accept that it’s changing.14

Editors said recruiting young journalists to local newspapers is also difficult. Geraldine Allinson, chairman of KM Media Group, said her company has struggled to retain and attract new talent.

Young people don’t see newspapers as a place where there’s going to be huge opportunities, so I think there’s that un-sexy, not cool side of things. Plus, a lot of people are very talented. Expecting people to do what they do for the money we can afford to pay them when other companies pay them a lot more is another difficult issue.15

Despite these challenges, interviewees see opportunities in the distinctive relationships they share with their readers and communities. Wayne Ankers, editor of the Huddersfield Examiner, said that although he asks his staff not only to cover breaking news but also produce video, photos, and social media posts, these efforts ensure that the newspaper can drive discussions.

If we start being the driver of the conversations that are important to local people, that’ll mean that people trust us more, come to us more, and want to have a dialogue with us more. … People don’t know what the Examiner stands for digitally, whereas they do know what we stand for print-wise. So, it’s getting people to trust us as a digital brand. I think that, once we’ve cracked that, our audience will continue to grow.16

Damien Allemand, chief of the digital newsroom for Nice-Matin, said that, in some cases, local and regional newspapers are using the same strategies as national media online or even leading them. For example, ‘For solutions journalism, there are national media who call us nowadays, saying: “How do you do this? How does that work?” because they’d like to do that themselves. Whereas before, that never happened.’17

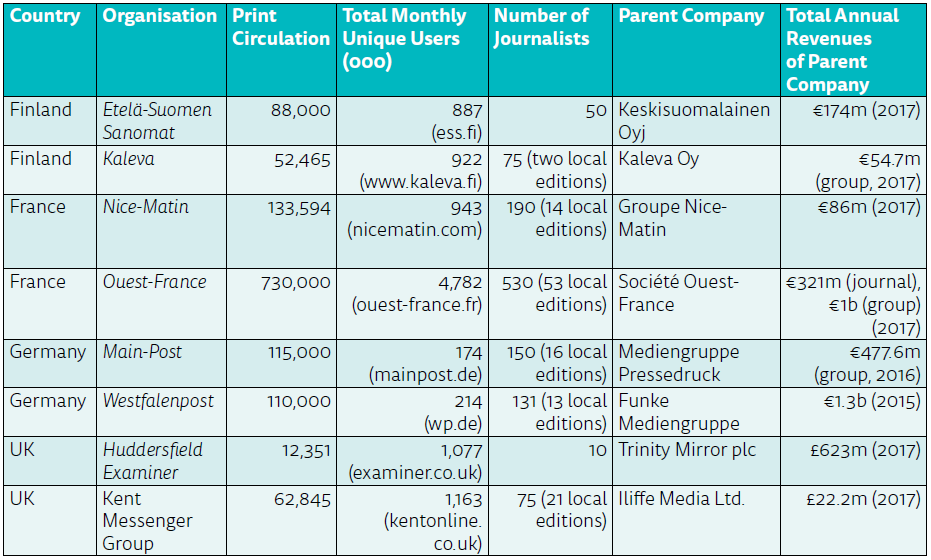

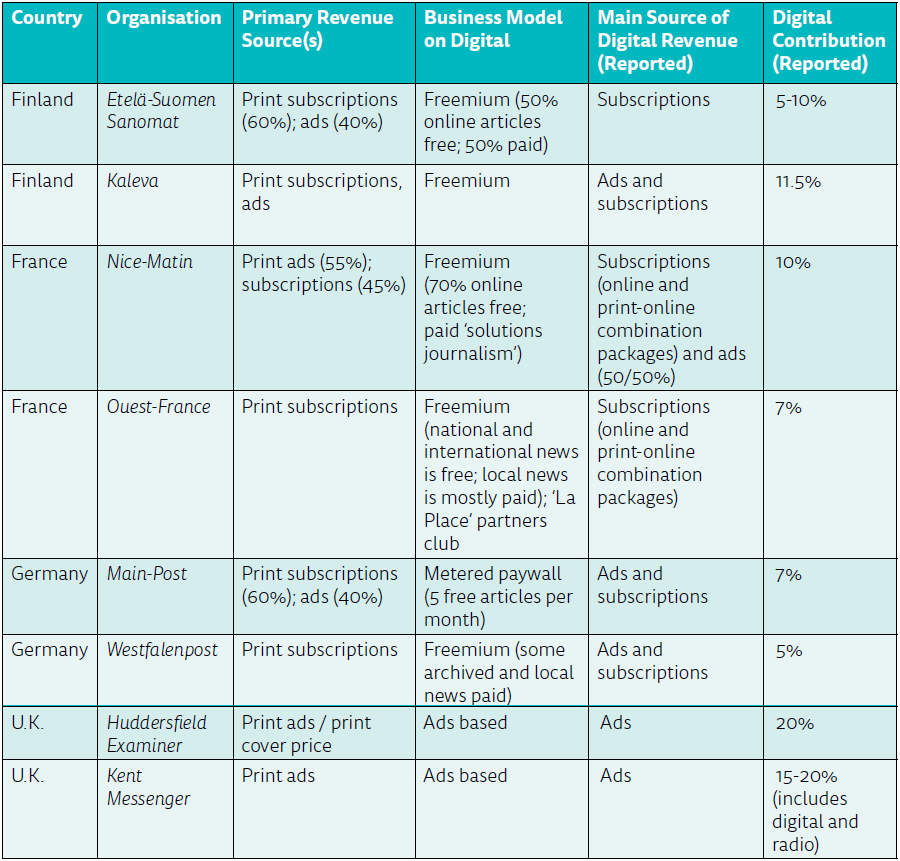

Table 1 highlights characteristics of the current media landscape for the countries covered, particularly in terms of digital news consumption and media advertising expenditures. Table 2 depicts the reach of the newspapers in the sample.

Table 1: Media markets for countries covered

Source: Adapted from Cornia et al. 2016: 13. Data: World Bank (2017) for population per country in 2016; Internet World Stats (2017) for Internet penetration in June 2017; Newman et al. (2017) and additional analysis on the basis of data from digitalnewsreport.org (calculation based on weighted base) for printed newspaper use in 2017, websites/apps of newspapers use, and social media use in 2017 (Q4. You say you’ve used these sources of news in the last week, which would you say is your MAIN source of news?), Facebook use for news in 2017 (Q12B. Which, if any, of the following have you used for finding, reading, watching, sharing or discussing news in the last week?), and for smartphone use for news in 2017 (Q8b. ‘Which, if any, of the following devices have you used to access news in the last week?’); WAN-IFRA (2017) for size of the national advertising market (total advertising expenditure in € millions, exchange rates GB£1.00/€1.17 31 Dec. 2016) in 2016, distribution of that expenditure across media, and changes in internet advertising expenditures 2012–16.

Table 2: Local and regional newspapers covered

Sources: Circulation and journalist numbers from interviewees; reach data from comScore (total unique visitors, Dec. 2017–Jan. 2018); ess.fi total unique visitors reported from interviewee (13 Jan.–12 Feb. 2018); total revenues from interviewees, Kaleva-Konserni press release 11 Apr. 2018 (www.kalevakonserni.fi/2018/04/11/kaleva-organisoi-toimintojaan-uudelleen-aloittaa-yt-neuvottelut/), Unternehmens-Register 2016 report for Presse-Druck- und Verlags-GmbH, and Trinity Mirror plc Annual Report 2017.

2. Streamlining Digital Editorial and Commercial Efforts

As consolidation continues to shape the management structures of local newspapers, particularly in Germany, Finland, and the UK, parent companies have developed strategies for streamlining editorial and advertising processes across their newsrooms, often to develop more efficient procedures for publishing digital content and attracting online advertisers (Hess and Waller 2017; Sjøvaag 2014).

The local and regional media companies in the sample, including Trinity Mirror, Johnston Press, Keskisuomalainen, Funke Mediengruppe, and NOZ Medien, discussed strategies such as company-wide content management systems, centralised newsrooms, training journalists how to better use analytics, centralised digital advertising platforms, and research and development departments for new editorial and commercial products.

This chapter focuses first on the organisational structures for digital editorial and commercial production that the companies have implemented or are implementing (2.1). The chapter then addresses how staff members describe the relationship between their newspapers and their parent companies (2.2).

2.1 Organisational Structures for Digital Production

Interviewees in the sample discussed diverse ways local and regional media companies are organised to enhance digital production. These efforts have been initiated to streamline the processes for creating online content, including articles, photos, videos, infographics, and other multimedia approaches, and make them available to newspapers to alleviate their workload and ensure they have content that is both online- and social-media-ready.

In the UK, Trinity Mirror is organised into regional centres, which create digital content, such as articles and videos, available to smaller newsrooms in their areas. For example, as editor Wayne Ankers explained, the Huddersfield Examiner publishes many ‘informational articles’ on its website, such as service articles, ‘because there’s quite a hunger for them’.

It’s a general area of interest everyone can relate to, no matter where they are geographically. Then, the central team will produce a video to go with that piece of content. So there’s a video explainer as well as the sort of traditional words and pictures. Then you decide whether that will be interesting to your particular readership.18

Each week, representatives from the regional centres, urban hubs, and county sites discuss what content has performed well on their websites, what stories newsrooms could incorporate, and new ideas for content, said Helen Harper, head of communities for Trinity Mirror Regionals.

During these meetings, Harper shares ideas for large-scale editorial projects in which newspapers around the company can participate, such as profiles of families to recognise World Prematurity Day, packages on mental health, and historical looks at communities (see Figure 1). To prepare for the World Prematurity Day coverage, Harper contacted Bliss, a UK charity focused on babies born premature or sick, which provided data as well as sources the newspapers could use. Harper said the coverage not only reflected the importance of the issue to readers but also allowed them to get involved and share their experiences:

So many people got in touch, with their own stories and sharing it, and I think that’s important, and also when you look at how much time people spent reading the article, it wasn’t just a quick flip-in-flip-out. They were spending time with it, and they were reading. They were genuinely interested.19

Figure 1: A sample of the coverage the Coventry Telegraph, a Trinity Mirror newspaper, produced for World Prematurity Day in November 2017

Trinity Mirror also hosts private Facebook groups where editorial staff members can share ideas with other newsrooms; provides two-day training seminars focused on topics such as digital storytelling and analytics tools; and offers in-newsroom training in which digital supervisors work alongside journalists on practical skills, such as learning a new content management system, said Ed Walker, editor (digital) for Trinity Mirror Regionals. Walker said the company’s digital audience growth has resulted largely from using analytics effectively:

This story might have had a lot of traffic, but did it all come from Google? Or did it come from Facebook? What are the demographics that are engaging with this story? Is it because it got shared by a specific Facebook group or page? And when you start to understand underneath that headline number, that really helps your story selection and your content decisions. … When we’re commissioning a piece of content, we’re very aware of what audience we’re writing for. And it’s not just about getting a big number; it’s about getting the right kind of numbers with that story.20

Trinity Mirror is working to better connect its 700 regional advertising representatives as well as ensure digital advertising experts are present within the regional centres to help support the other staff members, group digital director Piers North said.21

Johnston Press, which owns 300 weekly newspapers and 18 daily newspapers, as well as 323 local websites, manages digital hubs in London, Leeds, and Edinburgh. Mark Thompson, head of audience engagement for Yorkshire, oversees a digital team of ten staff members who work with 160 journalists and 26 newspapers across the region. He said his team ensures that the journalists report stories that can be published across outlets, and the team creates more ‘easily digestible’ content, such as short stories, lists, photo galleries, videos, and live blogs. He also tracks statistical performance and reports the results to the newsrooms to help them get more ‘mileage’ out of their content by adding photos, videos, and links and posting on social media.

When I started in journalism 11 years ago in a very kind of straightforward news team of writers, news desk, subs, editor – you could watch a story go through the system and you knew exactly what each step was. Whereas now the live reporter covers an incident, the digital team will see that and think, oh, we can do a bit more with that, I’ll head down and get some video, I’ll pull some tweets, create a list. The news team will then take that on, they will put the calls in, etc. … Before, we would just go step by step. Now it’s a bit more fluid, I guess. No single story will be dealt with the same way.

Johnston Press trains employees using the We Are Digital Academy, a website with best-practice guides on shooting and editing videos and attaching them to articles; in-house training on using social media, creating online quizzes, and other topics; and daily emails ‘reinforcing good practice’, Thompson said. Newsrooms are also encouraged to meet targets for page views (the company’s top revenue generator), video views, and social engagement. Ultimately, Thompson said, the company has made service journalism its main focus for revenue potential.

That’s when readers come to us not really because they want to read great journalism – they do – but they also want to know, can I get out of my house today because of the snow? Is my train going to be on time? Where can I go for a drink tonight? How well is my kid’s school doing? When do the bin collections start again after Christmas? … I think everyone has seen that actually, they are not silly stories; they are stories that affect everyone’s lives.22

NOZ Medien has launched a Hamburg-based research and development team, accompanying digital teams in Flensburg and Osnabrück, which focuses on two goals to serve the company’s 42 newspapers: (1) building technical ecosystems and infrastructure (i.e., content management systems for print and digital), and (2) content strategy.

Nicolas Fromm, managing director of digital for NOZ Medien/mh:n Medien, said the Hamburg team is developing an editing tool through which newsrooms can build ‘different storylines’ to enhance print content. The tool will allow editorial staff members to consider the potential audiences for their stories and add digital features, such as a live blog or a quiz. The editor will also provide data about how the article performs online, including commenting, sharing, and user demographics, as well as comparisons between different channels (the website versus Facebook, for example).23

The Hamburg team is working on two projects funded by Google Digital News Initiative grants: Ambient News, which aims to better understand readers’ daily news consumption habits and develop technical interfaces to provide them with content, and a project to increase the number of registered users on NOZ websites as part of a broader initiative to prepare for General Data Protection Regulation and offer personalised content for online visitors, such as suggesting content to them based on their interests or location.

Over the last five years, the Finnish local news industry has seen increasing consolidation, with companies such as Sanoma and Alma media acquiring new publications. Keskisuomalainen acquired Etelä-Suomen Sanomat in autumn 2016 and owns 61 other newspapers around Finland.

Kirsi Hakaniemi, head of digital business for Keskisuomalainen, said that although print accounts for the largest share of revenues for the company, it is also focused on developing new revenue sources, including online advertising, subscriptions to online articles and newspaper e-editions, and marketing and research services for B2B clients. To encourage these developments, Hakaniemi’s ‘digital hub’ of 20 staff members works with print and online editors to develop strategies so they can collaborate and ‘work more like a start-up’. This approach allows the company to treat its digital and traditional editions like a network or a bigger brand, rather than individual local companies.

As such, the company organises work groups, such as digital editors from the different newsrooms, who gather every two weeks to prioritise needs and develop best practices for topics ranging from social media to analytics to paywalls. As Hakaniemi described:

It’s better to share information and share all the analytics so we don’t have to – like, in Finland, we say that you don’t have to invent the bicycle again and again. But it’s a really big cultural shift, I think, and we are on the way. We have to do more and more communicating and sharing what we learn from each other. We have groups, which are sharing things, but we don’t have to do the same thing 10 times when we can do it one time and spread it everywhere and then use those leftover resources for other things.

Hakaniemi said the company’s newspapers have different approaches and structures for producing and monetising digital content – although Etelä-Suomen Sanomat is a digital-first newsroom, not all newspapers have advanced to this point – so her development team works to identify the best model for digital production and implement it in newspapers across the company. Her team, which is based in Jyväskylä, Lahti, Kuopio, and Vantaa and includes project managers, coders, a user-interface designer, analytics experts, B2B and B2C development managers, an AdOps team, and Google and Facebook ad specialists, has long-term goals, such as creating infrastructures for online registration, subscriptions, and display ads, as well as short-term projects, such as creating photos, maps, charts, quizzes, and other multimedia features newsrooms can easily integrate. As Hakaniemi describes:

They have the ideas and they get to talk about the ideas with my team, and then we will do the solution and help them to make the solution if they don’t have time to do it, or perhaps we can develop a tool that the editorial department can use again and again to give the stories more reach.24

Keskisuomalainen also includes a centralised editorial desk providing national content to its affiliated newspapers.

In Germany, Funke Mediengruppe, which owns Westfalenpost, reorganised its digital production after buying two newspapers and several magazines in Berlin and Hamburg in 2013. The company implemented a central newsroom in Berlin that produces national and international economic and political news for the company’s 12 regional newspapers. Funke also incorporated a Berlin-based digital unit that serves as a linking unit between the different newspapers, newsrooms, and departments and that works on requests, such as developing news apps, which other Funke newspapers can also use.

Martin Körner, a communications associate for Funke, said the centralised-unit approach not only uses the company’s resources more effectively but also allows its affiliated newspapers to spend more time reporting local news.

When there was a football game, for example, there were at least four reporters from every single [newsroom] who went there. And then they said, ‘Well, that’s not efficient. … We don’t need four people to write about the same event.’ But we can say, ‘This one guy – the best football journalist we have – goes there and can write this article for several titles so we have the best possible content.’ And the other three journalists can focus, for example, here on premium and high-quality local news.25

2.2 Relationships with Parent Companies

Our interviewees from local newspapers that are part of groups pursuing a regional-breadth or national-scale approach often highlighted the advantages of being part of a larger company offering them resources, training, and support they would not have access to otherwise. These responses are unsurprising, as local and regional players and larger companies with declining legacy revenues have been challenged with identifying resources for digital investments and experimentation (Cornia et al. 2016). In contrast, interviewees at titles pursuing a localisation strategy saw their freedom to tailor their approach to their specific community as a distinct advantage.

Lauren Ballinger, executive editor for the Huddersfield Examiner, said the newspaper’s connection with Trinity Mirror ensures that her newsroom maintains a digital-first philosophy. Trinity Mirror also provides page-view targets for its desktop, mobile, and app traffic, as well as video targets. She said meeting the targets can be difficult.

We just follow their lead really, because that’s what they – I mean, you’ve got to have some autonomy I suppose, because we are an individual local title. So you’ve got to listen to your own readers, which are very different here from Manchester, for example, because that’s a big city. And it’s good that Wayne’s come, because he used to work at the Manchester Evening News. So it’s good he’s come from there, because he can see how different the two audiences are; you’ve got to respond differently.

Ballinger said she appreciates the connections with other Trinity Mirror newspapers, including multiple weekly conference calls, which she said are generally but not always useful, as well as other opportunities for sharing ideas and content, particularly national trend stories.

There are a lot of Facebook groups, where everybody shares ideas and asks questions, so that’s really good as well. And we have central teams … and we get emails all day, every day. So this morning in the conference [call], I had a print-out of trending videos that the trending videos team put together, and they’re there for anyone to use. That’s one thing that I think Trinity Mirror does really well at … having a central team that creates things. They’re out of the newsroom, so they have time to strategise.26

Huddersfield Examiner editor Ankers echoed these benefits.

Certainly for me, being a new editor, I can speak to other editors, benefit from their experience, bounce ideas off them. What Trinity Mirror is good about is training. … There are regular workshops with editors and senior managers so that we can share ideas and work together. I think that’s invaluable.27

Haukilahti, regional manager for Etelä-Suomen Sanomat, said the newspaper’s sale to Keskisuomalainen offered an opportunity to ‘ensure that local news in this community … would continue’. With a company the size of ESS, developing new digital tools for editorial and commercial purposes can be challenging, he said, so working with the company’s digital team alleviates those pressures. ESS has also benefited from access to centralised content, with 30–40% of editorial originating from outside the newsroom.

It doesn’t matter who owns it because the stories in the newspapers are still the same. The owners don’t tell us what to write. We are independent to do what we want. And that has been understood here. If you don’t work like that, you don’t have a long future.28

As part of the Keskisuomalainen network, the ESS news desk also works closely with three other newspapers, with which the newspaper shares stories. News editor Markus Luukkonen said he speaks weekly with editors at the other papers to create editorial plans for the week. The four newspapers also share a Jyväskylä–based virtual news desk, which includes eight journalists who cover national news.29

Main-Post is owned by a family-owned company, Mediengruppe Pressedruck, which also owns the Augsburger Allgemeine and Südkurier Medienhaus. Julia Back, an editor for Main-Post, said she appreciates the security of being connected to a larger company.

I know it costs a lot of money to change the work process, to invest in digitalization of our newspaper. So it’s more comfortable to be in a publishing house that is performing very well, where they can invest in the transformation. I think it’s harder for small newspapers, for small publishing houses to change everything.30

KM Media Group, which publishes nine paid-for and four free newspapers, as well as oversees KentOnline.co.uk, the kmfm radio network, and KMTV, was acquired by Iliffe Media Ltd. in April 2017. Chairman Geraldine Allinson said Iliffe Media, which was incorporated in fall 2016, was the best owner for the company, whose revenues had been hit by the move toward digital advertising and a growing pension liability that could only be addressed through an ownership change. KM is working to reorganise its editorial department, and eventually production and advertising structures, so it can better operate within the larger company.

[The sale] helps us a lot because that means we can share costs because other parts of the group will start using our infrastructure, and some of the system decisions will be based on the fact that we need to talk very easily across the group and work on the same systems rather than all be building interfaces.31

Other concerns about consolidation in the local and regional newspaper market have also emerged. For example, Trinity Mirror, which acquired regional publisher Local World in 2015 and Northern & Shell Media Group’s Express Newspapers in 2018, in addition to its extensive existing local and regional newspaper holdings, recently drew criticism from the National Union of Journalists for a new standalone digital business model, the ‘Live’ brand, which could result in the elimination of nearly 100 positions in an effort to create separate print and online teams (Mayhew 2018a, 2018b). Both Trinity Mirror and Johnston Press also closed several weekly local newspapers in 2017.

3. Creating a Digital-First Culture

Editors-in-chief, managing editors, online editors, reporters, and others discussed the ways their newsrooms have adapted to the changing habits and preferences of their target audiences. Their digital-first focus has shaped newsroom roles, structures, and processes. In particular, interviewees discussed integrated versus non-integrated online desks, social media use and expectations, the role of video and multimedia storytelling, the rise of mobile consumption and apps, and working with start-up and tech developers.

These trends reflect shifts facing national and international private-sector media as well. Like national news organisations, the local titles covered here receive a large majority of traffic from mobile devices, as well as search and social, and are investing in online news video (Cornia et al. 2016).

Interviewees addressed the need to better understand their audiences through analytics, surveys, social media, and other tactics so they can connect with them based on interests, location, and demographic qualities, spurring new editorial products and marketing strategies.

This chapter first focuses on the organisational structures for digital editorial and commercial production within newsrooms (3.1). The second part addresses the role of social media in newsrooms (3.2). The final part (3.3) examines how staff members describe their audiences and how they are working to maximise – and monetise – these relationships.

3.1 Newsroom Structures for Digital Production

Most newspapers in the sample maintained separate desks in their newsrooms for digital production, although some also emphasised that all editorial staff members become involved with publishing articles online and incorporating multimedia content, as well as considering article performance through analytics. Other newsrooms prioritised digital experts tasked with maximising the online performance of articles and testing new tools.

The Finnish newspapers in the sample featured separate online desks while promoting a digital-first culture. At Etelä-Suomen Sanomat, section editors for news, sports, and culture focus on both the online and print products, while an online desk of four to six staff members covers breaking news and posts content from the other reporters online.

Kaleva considers itself a digital-first newsroom and maintains a separate online desk of six or seven staff members, who post articles and develop multimedia presentations. Web editor Niiles Nousuniemi said that although its online traffic has been higher than in other regional media houses in Finland, Kaleva is working to better integrate its digital and print activities. Kaleva also uses a bot named Clara to handle about 40% of online comments.

We’re bringing our print journalists closer to the online desk, and they’re learning how to use tools and learn new skills. We’re also trying to change the thinking of how to create stories and help with those. We are moving to a digital newsroom.32

The German newspapers have worked to more closely integrate their digital and print newspapers. Westfalenpost uses a project-based editorial approach (see Figure 2), which involves planning content not only on a daily basis but also thinking more long-term: developing themes that the staff cover through multiple print and online articles, as well as photos, videos, and podcasts, from local crime to envisioning the future of the region, said Jost Lübben, editor-in-chief.

Westfalenpost’s crime series, published in November 2017, focused on cold cases in the region and included articles, podcasts, and videos (Figure 2). Journalists from across the region collaborated for eight months to report the series, and a designer in Berlin produced the graphics in cooperation with the newsroom. Lübben said of the project:

The power for new things, creativity, was in the newsroom. And if you put people together and let them work and give them the time and the liberty to think and to develop things, especially if they usually do not work together … they do a fantastic thing.33

Figure 2: Westfalenpost’s crime series

In 2011, Westfalenpost developed a regional ‘cluster’ to oversee the local sections of the newspaper. The regional desk includes four online editors, who have become a hub for ‘online know-how’, digital editor Torsten Berninghaus said, a support desk for online layout, graphics, multimedia features, copy editing, and other aspects of digital production. The editors are each responsible for two or three departments and travel to those newsrooms to provide support.34

Lübben said that although the newspaper has a separate digital desk, he is working to make all the desks more digital. For example, the South Westphalia Desk, which oversees the local departments, has a new creative team – implemented in autumn 2017 – that meets weekly to plan multimedia content, such as videos and graphics, for the following week.35

Main-Post has worked to spread an online mentality among the editorial staff, such as hosting ‘Digital Thursdays’ in which staff members learn how to produce online teasers, headlines, and videos. Like Westfalenpost, Main-Post aims to better plan its print and digital news offerings through an approach Andreas Kemper, managing editor, called ‘theme management’. A team of three theme editors evaluates local news topic suggestions and determines whether to publish in print, online, or both; broaden the topic from the local edition into the regional newspaper; add a video or other multimedia component; create a special delivery approach for mobile; and post it at a certain time of day. The strategy, implemented in October 2017, has resulted in a 15% increase in page impressions because users can easily find the stories and are primed to check back for updates, Kemper said.

For example, after six young people died from carbon monoxide poisoning from a gas generator operated by their father, the newspaper offered in-depth coverage of the case and the response in the local village in the print edition, then covered the trial itself and continued to update the details of the trial online. Kemper said that, although the newspaper is covering the same topics and producing similar content, ‘we can now manage it much, much better, and we get more of our really good content out of the local bureaus’.

Kemper said the strategy enables Main-Post to reduce costs while producing more quality content about the region. As such, it emphasises reaching loyal print readers while drawing new audience members online. As Kemper described, ‘Our reporters are like a regional agency, producing content and delivering it to the consumer, no matter which channel.’36

Theme editor Folker Quack described an article focused on a man in a small town who built a city out of Lego bricks. Because he perceived the story would attract broader interest than just that town, Quack placed it on the front page of the newspaper and high on its webpage. As Quack commented: ‘Do we want to make this as the first article in just the local part of the newspaper? No. We need this for all the people.’37

Shz.de is an online news portal for the Schleswig-Holstein region in Germany and publishes content from 22 NOZ Medien newspapers. The online team for shz.de includes ten staff members, with three video reporters and seven online editors, who are based at different newspapers around the country. As Mira Nagar, a digital editor based in Flensburg, described, the digital editors review content produced by the newspapers’ reporters and determine what would be interesting for a broader audience, adding new features and interpretation.38

Joachim Dreykluft, a digital editor for shz.de, said he is not convinced integrated newsrooms are the most effective approach for regional newspapers because of the chasm between approaches to print and digital journalism.

I think digital journalism is something very different from print journalism. It has a different rhythm over the day. We work at different times. We have users that use us at different times of the day. … The type of content we need for this is totally different. When you are telling a story in the newspaper, all you have is written text and photos. In digital journalism, we have much more you can use to tell stories.39

In developing its digital-first approach, Ouest-France aimed to transform the business digitally while preserving its print newspaper and subscriber base. Édouard Reis Carona, editor-in-chief for digital content and innovation, said Ouest-France aims to post all content online first, reserving exclusive reports for the print edition, which also emphasises ‘more analysis, more interpretation, more commentary, and less real-time news’.40

Ouest-France has also digitised its entire archives – 42 million searchable articles – and launched an evening edition in 2013 (see Figure 3), the first digital-only newspaper in the country. It is published from Monday to Friday at 6 p.m. The digital project includes news, background stories, interviews, photos, and videos in a magazine-like format. Chief sub-editor Corinne Bourbeillon said, ‘It’s not breaking news; it’s something different. People like good stories.’41Ouest-France began publishing a newspaper for children, ‘Dimoitou News’, in 2015.

Figure 3: Ouest-France’s ‘L’Édition du Soir’ (‘The Evening Edition’)

Ouest-France is also reorganising its newsroom to emphasise its digital approach, such as incorporating regional steering teams of three editors who determine whether content will be posted in print, online, or both, with a fourth editor focused on social media. In autumn 2018, the company’s regional offices began transitioning to the EIDOS system, allowing them to use a single tool to produce both print and online content, as well as upload stories from their iPhones, said Fabrice Bazard, director of digital activities.42Ouest-France has also created a start-up accelerator to develop digital tools, such as artificial intelligence, video, and podcasts.

Ultimately, however, Ouest-France is focused on involving all of its journalists in its digital transition, editor-in-chief François-Xavier Lefranc said:

There are some newspapers that have said, we’ll sack half of them and then we’ll recruit youngsters. We didn’t make that choice, and right from the start we made it known that we wanted to bring everyone with us. The whole editorial team had to grow and get up to speed. It’ll take time, a colossal effort, loads of instruction, lots of goodwill, too, because not everyone progresses at the same speed. But we took the gamble, and we did it because it’s a company that has this in its values – this makes even more sense when we say it today. We really wanted everyone to be able to adapt.43

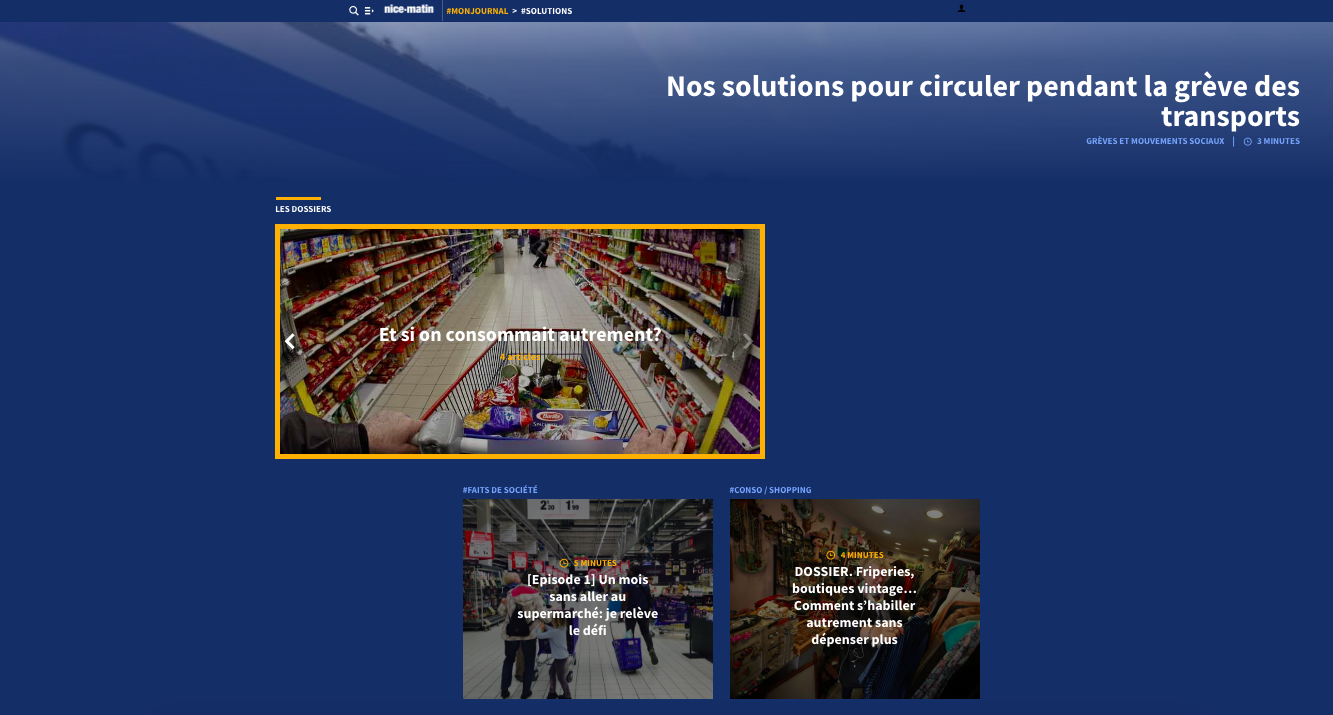

Nice-Matin’s digital strategy emphasises long-form solutions journalism (see Figure 4). Damien Allemand, chief of the digital newsroom, described this approach as taking the journalistic focus on the five Ws – who, what, when, where, why – and adding the ‘Now what?’

When I read the newspaper, I get depressed because there’s only bad news. They tell me, this has happened, it’s dramatic, it’s not normal, it’s controversial. I’ve never before been given the key to resolving this thing. But afterwards, the aim is not for the journalist himself to find solutions; it’s actually that he seeks out people who have found solutions.

The solutions journalism audience averages between 40 and 45 years old and largely comes from Nice and the surrounding region. Topics have included improving public transportation, reducing food waste in local schools, and the problem of wolves eating local farmers’ sheep. Allemand said:

There are a lot of wolves, and they eat sheep, so the shepherds aren’t happy. So we put together a file in which we, first of all, explained that it’s a problem, with lots of data. And afterwards, we went to see shepherds who had found solutions, and so we presented their solutions for successfully living alongside wolves. For example, there’s one shepherd who set up little lights around his animals to frighten the wolves. Another one reduced the size of his flocks so that they could be watched over more easily. So this became a topic with positive initiatives and which can serve as an example for others.

The efforts have paid off. The newspaper’s solutions journalism, which is produced by a video editor and three journalists, accounts for the most subscriptions of its online content, as well as drawing consistently positive comments on Facebook (the content is also featured in a four-page Sunday section in the print newspaper). In 2015, when the project was launched, it attracted 1,500 subscribers; that number has since grown to 8,000. Subscribers, who pay €9.90 per month and receive updates via an e-newsletter, can also vote each month on which topics the team tackles next and suggest ideas.

Allemand said solutions journalism has already spurred change, such as a feature on an area school’s response to lunch waste – determining portions based on age – being adopted by other schools in the area. After the terrorist attack in Nice in 2016, the newspaper launched Facebook groups to centralise aid appeals and organised collections for those affected. Subscribers to solutions journalism are invited to attend special events, such as newsroom visits to discuss upcoming coverage and recognise community helpers featured in articles. ‘They are very happy to get involved,’ Allemand said. ‘They are far more engaged than a normal reader. They spend a lot of time on the articles, they share them. They are our primary ambassadors.’44

Figure 4: Nice-Matin’s solutions journalism homepage

Reporter Aurore Malval said that while the newspaper’s solutions journalism emphasises local sources, it also gives her flexibility to explore topics with national and international interest, such as school bullying, sexual consent, and online extremism.

If I can find a local expert, it’s better for my audience because then it’s regional, but it’s for me not so important as it is in the print [newspaper]. For example, I’m more in a position to deal with a national theme than in the print paper; it will be different for me in the content. If I bring a small story and if nobody is local, it can be OK for me.45

In addition to the solutions journalism team, Nice-Matin has an online desk in its central office in Nice. The desk includes ten staff members focused on producing breaking-news content, in addition to a social media editor and two video editors. The newspaper aims to post at least one video per day made specifically for Facebook and is working with start-ups to generate videos more easily and quickly, including Facebook Live videos.

The UK newsrooms have continued to reorganise to emphasise online production. At the Huddersfield Examiner, the online team includes a breaking news reporter, online content writer, and videographer, as well as three digital production staff members. Executive editor Lauren Ballinger said that completed news stories are filed to print and digital production simultaneously. The goal is to ‘keep the website fresh, keep something going out every half an hour to an hour, and every 45 minutes trying to put something on Facebook’.46

Wayne Ankers, who arrived in spring 2017, has implemented other changes, such as changing shift patterns so the newsroom is staffed in the evenings and on weekends, encouraging staff members to post stories at times of day when traffic spikes, incorporating screens where staff members can check site analytics, and discussing how to approach online versions of stories. The newspaper’s website traffic has continued to grow as well as app subscriptions.47 Ballinger said Facebook and push alerts also draw traffic.

Breaking news reporter Susie Beever said her position at the Huddersfield Examiner often focuses on ‘very routine, small crimes and weather updates, travel updates, things like that’. She said she most enjoys reporting a positive human-interest story or breaking news that draws immediate interest from readers. For example, she described providing live updates on a suspicious fire at an old mill.

That was one of the biggest stories of the year, and it did so well. I just remember leaving that day and just feeling really pleased with myself because I know that I had given it my all. The interest was so big, and I think one of the rewarding things is just seeing the figures. Seeing you break out a story and seeing hundreds of people on it instantly, you just think, wow, people are listening to what I’m saying.48

Like the Huddersfield Examiner, Kent Messenger has implemented a content management system allowing staff members to prepare their work both for print and online. Each local edition has its own website, in addition to the primary website, Kent Online, which is overseen by three editors. In drawing traffic, however, editors said they resist clickbait, editorial director Ian Carter said.

We try not to frustrate our readers, where the opposition has a tendency to frustrate an awful lot of readers. And again, that’s taking the long-term view that yes, you might get a click out of them, but what does that do for you as a business in the long-term?49

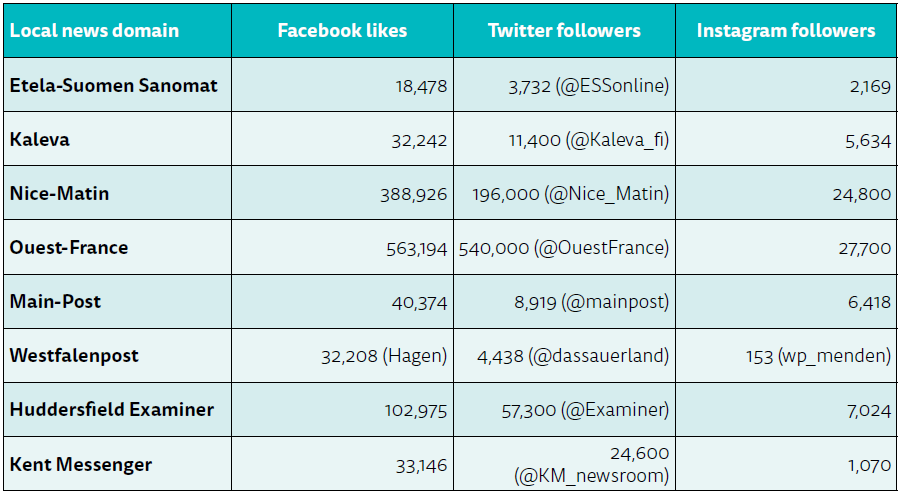

3.2 The Role of Social Media

Interviewees also discussed the functions social media serve for their newspapers (see Table 3), with many citing Facebook as a key driver of traffic, although some expressed concern about how much influence the platform exerts. Interviewees also discussed social media as reporting tools and ways to share content with particular community members.

Kirsi Hakaniemi, head of digital business for Keskisuomalainen, said Facebook is most important among the social media platforms the company focuses on, but it is not where younger users are active. She said WhatsApp is becoming more important for reaching that group.50 Similarly, Keskisuomalainen content manager Silja Tenhunen said traffic via Facebook is actually decreasing because some readers shift to communication via WhatsApp during the day:

In the morning we have quite a lot of readers with mobile, but in the afternoon, there’s nobody here. If you ask why, they are in WhatsApp. For example, if you have children, you go to the WhatsApp and ask … or are you going to the ice skating rink in the evening and things like that, and when you do it, you are not in the Facebook. That’s why it’s not very interesting to put our stories online at the same time because nobody is there. They’re in WhatsApp.51

Édouard Reis Carona, editor-in-chief for digital content and innovation, said Ouest-France animates its community on Facebook, which represents 15% of social traffic. He said, however, that editors do not want to become dependent on the platform and are selective about the amount of original material they post, about 30 posts a day.

The things we put on Facebook, some small videos and then a bit of Facebook Live, but that’s all. … We have a community of about a million people, counting all of the Facebook pages. It’s a very committed community because we reach more people than the national papers, because these people are very attached to the Ouest-France brand.

Reis Carona said Ouest-France is also seeing growth with its Instagram account, where editors post two to three stories daily, while Twitter functions more as a ‘monitoring tool for journalists’.52

Nice-Matin similarly revisited its Facebook strategies in light of the realisation two years ago that 60% of traffic on its site originated from the platform. Allemand, chief of the digital newsroom, said, ‘We were scared about that. So we reduced the number of posts that we put on Facebook every day.’ Now, 25% of traffic comes from Facebook, and the site’s overall traffic has increased. Nice-Matin is also developing its Instagram presence. Allemand said:

We’re trying to do something different on Instagram, where we do stories. At the moment there is a journalist here who is telling the story of a little girl who has cancer and who goes to see Father Christmas, and who is following her, and so he’s doing a story on Instagram. And afterwards we’ll try to adapt to Instagram language so as to try to provide information, so we’re creating small modules like that, photos and text.53

At Westfalenpost, every local department operates its own Facebook page. Digital editor Torsten Berninghaus said this approach differentiates the newspaper from other German media:

Every local office has its own Facebook address, and that is special – several newspapers in Germany only had one or two Facebook accounts – and it’s an account for the whole newspaper. What they do is mirror what is in the newspapers, give it to the audience, and that’s it. Our offices’ chiefs addressed us, and they told us, ‘No, we want to be relevant in our local communities, so, what has our audience learnt from the newspaper?’ … So, we are focused on local news, and that’s where we want to have the Facebook accounts.54

Westfalenpost managing editor Michael Koch said Facebook offers the newspaper access to audiences it might not otherwise reach, ‘especially young people, especially people from immigrant families, poor people who don’t have the money to buy a newspaper. So we have more Facebook friends than subscribers.’ He said reporters also use Facebook to connect with groups and sources: ‘It’s like a news agency for us.’55

Similarly, Huddersfield Examiner’s Martin Shaw espoused the benefits of the platform for connecting with story ideas and sources:

You can really find a huge amount of stories. Once you’ve got opportunities, you’ve got a circle of friends and you’re members of all these different individual, local groups on Facebook. It’s an absolute mine of stories. It makes it almost too easy. … When you have access to all these great stories that people are talking about, and you know they’re going to be fantastic for your figures, why wouldn’t you be all over social media?56

Nicolas Fromm, managing editor of digital for NOZ Medien/mh:n Medien, said the company has a loyal Facebook community – each of its 42 newspapers has its own Facebook page – and uses Facebook to promote its e-commerce. He said that despite the traffic NOZ content receives from Facebook, he has reservations about the platform overall.

The problem with Facebook is that it is a very closed shop for us. So even Google is way more open to innovation and to working together with publishers than Facebook is. Facebook is always inviting you to [a] big conference and they’re announcing something. And it’s exactly a week later they are doing the opposite. So that is a big problem for us. Google is really easier to work with.57

Ian Carter, editorial director for Kent Messenger Group, said up to 40% of his newspaper’s traffic originates from Facebook. However, like many of the interviewees in the sample, he takes those results with a grain of salt.

Those Facebook users are your least valuable readers because they stay on your site for 10 seconds. They don’t care which site they are actually visiting. Your bounce rate goes through the roof, and there’s no loyalty in a Facebook reader. And your Facebook’s a whim. They can change the algorithm, as it does all the time. Last month we saw a 14% decline in Facebook referrals because of a tweak. So you have no control over it.58

Few of the interviewees said they focus on using Facebook as a viable advertising venue. Kaleva business manager Juha Portaankorva said, ‘It’s a good way to focus and collect people who live in a certain area and have certain interests; that’s kind of where we are using it.’59

Mark Thompson, head of audience engagement for Yorkshire, said Facebook is the company’s top referral source, although Johnston Press is exploring other platforms.

Instagram, Snapchat, they are not going to give us big page referrals, so they are not going to drive a lot of traffic back to our sites. [ … ] Because we know there is a big audience there, we can use them almost as PR tools for our business and what we are doing. We can use it for UGC so people feel involved in the community by posting their photos, and us ‘behind the scenes’ in the newsroom. I’ve seen them done really well, but they are still new, very fluid, and no one really knows what they are going to look like in a couple of years’ time. I think Facebook and Twitter are so news heavy now that people kind of know what to expect, but I do think that will change; I think Facebook will change quite radically over the next 12 months.60

Respondents also discussed the role of Google in their organisations, with many using Google products in their daily work, particularly Google Analytics. They also frequently referenced the importance of Google as a traffic driver to their websites, accounting for between 20 and 40% of traffic across the titles. Some organisations, such as Ouest-France, Nice-Matin, NOZ Medien, and Trinity Mirror, also use Google AMP and praise the speed and access it offers to local audiences.

Interviewees also continually referenced Google and Facebook as competitors in the local advertising market. For example, Juha Honkonen, managing editor of Etelä-Suomen Sanomat, said:

The bad thing is that prices of ads are falling, so they’re [ads] not so important now as they used to be, and they’re not so important after some years when Google and Facebook are putting their costs and their prices so low. So, the readers are going to be more and more important.61

Some interviewees said they see Facebook and Google as opportunities, if news organisations can determine how to maximise them. As Ed Walker, editor (digital) for Trinity Mirror Regionals, said:

When you look at Facebook and Google, they are always changing and adapting and evolving. And it’s up to us to understand how we can leverage that to support our growth for scale or for engagement. And, you know, the reality is that both of those offer an opportunity to do both of those things. You just have to understand how to do it for the type of content or the type of community that you’re serving.62

Table 3: Social media presence (at 20 March 2018)

3.3 Understanding Audiences

The newsrooms’ transitions to digital-first publishing emphasised new ways of thinking about their audiences. In most cases, the newspapers reached far different audiences online than with their print products. They also aimed to draw broader and younger audiences online.

Fromm, managing director of digital for NOZ Medien/mh:n Medien, said the company’s websites draw younger readers than their print newspapers; however, they are not explicitly interested in news from their city or region. Rather, they are looking for more aggregated and engaging content. As a result, the company has incorporated a CMS that allows reporters to create different versions of articles to appeal to different types of readers – different headlines and photos, for example – as well as different versions of articles for the website, social media, and messaging apps. He emphasises understanding ‘user journeys’ to recognise newspapers’ most loyal audience members, including e-newsletter subscribers and a growing WhatsApp community, which receives a list of four essential local articles to read that day.63

Thompson, head of audience engagement for Yorkshire, said Johnston Press is focused on using analytics to understand what audiences want.

What newspapers used to do was, everyone would sit in a news conference and have a chat and they would choose the front page based on what they thought, rather than any kind of proof of what people were interested in. What we are learning now is that people are interested in a lot of different things, and I think diversity is the way forward for us.

He said Johnston Press has a product called City Buzz, an SEO-optimised WordPress site integrated into Leeds newspaper websites that offers tips for places to eat, drink, and stay in the area based on user data.64

Silja Tenhunen, a content manager for Keskisuomalainen, said the company relies on user profiles: Johanna, a mother who wants short stories in the morning and longer, emotional articles in the evening; Maria, a single woman or a woman with no children who works and lives in the city and wants to know about public transit and other news about her community; and Seppo, a 55-year-old man who wants to know about local politics and comment about them online. These understandings shape not only how journalists think about what topics and story approaches to pursue but also where to share content, such as in Facebook groups.

When you think, for example, Seppo, you have to know your numbers and you have to find which one online is Seppo. That’s why analytics is very important to us because if you just look at the numbers, as numbers, you see that’s good, but … you have to know more about your numbers. For example, it’s not enough that you see that people use their mobile phone. You have to think why and what I can do so that users on mobile phones are happier when they read the stories.65

At Kaleva, staff members target articles to particular groups within the community, which they assess through sending text messages to ask for quick feedback and organising events, such as a flea market, to meet and talk with readers. Portaankorva, business manager for Kaleva, said:

Because, in our way of thinking, if the newspaper needs to give some kind of information for everyone, a story for everyone, it means that those articles and those stories are just mainly – if you write for everyone, who are you touching?66

In autumn 2016, Westfalenpost began a pilot project to identify target groups among loyal readers and develop distribution strategies to appeal to them. They drew from not only their own user data but also public information sources, such as census data on population, age, and gender. As editor-in-chief Lübben described:

These are target groups: families with older children, silver birds, people older than 60, for example. We describe them exactly. They’re profiled. … It’s very important for the digital stuff we offer because if you do not have a target group in mind, how can you create good news, for example, for target groups under 30? It’s not possible.67

Ouest-France is working to connect with online users who come through social media but are not particularly connected to the brand and convert them into print subscribers. Eric Bullet, monetisation manager, said the company has developed a partner club, ‘La Place’, to which online users can subscribe by registering their email addresses. Once they join, they have access to events, opportunities to accompany journalists on reporting assignments, meetings with artists and others in the community, and ticket giveaways.

They are pampered. And in parallel, we wish to increase our audience. We tell ourselves that the stronger our audience, the more we can reach new subscribers with this ‘ouest-france.fr plus’ offer in the future.68

Nice-Matin is also working to better understand its audience’s interests so they can create more valuable content, said Allemand, chief of the digital newsroom.

At the moment, we have an offer that is tailor made for our subscribers, based on their tastes, but they have to tell us what these are; what’s at stake in the future for us, it will be to make a subscription offer where people don’t have to say at the start that they like sport, that they like politics, and that they live in Nice, but we’ll know these things, and we’ll be able to put together a newspaper for them based on their centres of interest.

Allemand added: ‘The law of proximity no longer applies.’ Readers are focused on ‘topics rather than towns’. He said the Nice-Matin staff has used A/B testing to determine what types of headlines and stories draw clicks, finding that the newspaper can draw a wide audience based on the topics it covers.69 Other editors, such as at Ouest-France, the Huddersfield Examiner, NOZ Medien, and others, echoed this potential for their web products.

4. New Business Model Approaches