In this RISJ Factsheet by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen and Lucas Graves, we analyse data from 8 focus groups and a survey of online news users to understand audience perspectives on fake news.

On the basis of focus group discussions and survey data from the first half of 2017 from the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Finland, we find that:

- People see the difference between fake news and news as one of degree rather than a clear distinction;

- When asked to provide examples of fake news, people identify poor journalism, propaganda (including both lying politicians and hyperpartisan content), and some kinds of advertising more frequently than false information designed to masquerade as news reports;

- Fake news is experienced as a problem driven by a combination of some news media who publish it, some politicians who contribute to it, and some platforms that help distribute it;

- People are aware of the fake news discussion and see “fake news” in part as a politicized buzzword used by politicians and others to criticize news media and platform companies;

- The fake news discussion plays out against a backdrop of low trust in news media, politicians, and platforms alike—a generalized scepticism toward most of the actors that dominate the contemporary information environment;

- Most people identify individual news media that they consider consistently reliable sources and would turn to for verified information, but they disagree as to which and very few sources are seen as reliable by all.

Our findings suggest that, from an audience perspective, fake news is only in part about fabricated news reports narrowly defined, and much more about a wider discontent with the information landscape – including news media and politicians as well as platform companies. Tackling false news narrowly speaking is important, but it will not address the broader issue that people feel much of the information they come across, especially online, consists of poor journalism, political propaganda, or misleading forms of advertising and sponsored content.

General overview

The flow of misinformation around the 2016 US presidential election put the problem of “fake news” on the agenda all over the world. Precise definitions, when offered, often deal narrowly with fabricated news reports produced either for profit or for political purposes (Wardle 2017).

But the term is in practice used much more broadly than the high-profile examples of false content fabricated in pursuit of advertising revenues, for instance by the now-infamous Macedonian “fake news factories” (e.g. Subramanian 2017), or as part of statebacked misinformation campaigns. People also use it to cover tendentious news coverage, partisan rhetoric, and false or outrageous statements by politicians, all spread via social media and other platforms and often amplified by news media. Furthermore, the term has been effectively weaponized by critics of established news media to attack and undermine the credibility of professional journalism.

The public discussion around fake news has so far been dominated by journalists, technology companies, and policymakers, and by a community of academics and think tanks committed to engaged scholarship (e.g. Wardle 2017, Marwick and Lewis 2017, Bouengru et al 2017, Howard et al 2017). The purpose of this RISJ Factsheet is to map audience perspectives on fake news to provide a bottom-up supplement to a debate that has so far been top-down, with little analysis of how ordinary people think about the problem of fake news.

We provide this analysis of audience perspectives on fake news on the basis of a mix of qualitative and quantitative data from the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Finland, including data from 8 focus groups and data from a survey of online news users. Both the focus groups and the survey research covered a wider range of topics as part of our larger Digital News Report project (Newman et al 2017, Vir and Hall 2017), but also included specific questions focused on issues including fake news and trust in different kinds of media.

Structural shifts underlying the fake news discussion

Two underlying structural changes provide the backdrop for current discussions around fake news.

The first structural change is a widespread crisis of confidence between news media and other public institutions including politicians and much of the public in many countries (Norris 2011, Ladd 2012, Nielsen 2016). This crisis is not uniform, but it is pervasive enough that significant numbers of citizens even in otherwise high-trust countries like Finland are highly sceptical of much of the information they come across in public spaces today, whether heard from politicians, published by news media, or found via social media and online search. It is clear that in for example the United States, this decline in trust began well before the advent of digital media, and that it is driven in part by a partial tabloidization of the news landscape and rising political polarization, accompanied by a diminished sense of common ground and more frequent and intense political attacks on the news media (Ladd 2012).

The second structural change is the move from a twentieth-century environment dominated by broadcast and print mass media to an increasingly digital, mobile, and social media environment. Publishers are still critically important as producers of news in this landscape but play a less central role as distributors and gatekeepers, as audiences have greater choice and as a small number of large platform companies increasingly shape media consumption through services like search, social media, and messaging applications (Bell et al 2017, Nielsen and Ganter 2017). In this environment, it is easier to publish any kind of information, including false and fabricated information. While several

independent pieces of research suggest that even in the United States, only a minority have actually been exposed to demonstrably fake news stories (Guess, Reifler and Nyhan 2017), and that these stories have in most cases made up only a very small fraction of people’s total information exposure (Allcott and Gentzkow 2017), there is clearly a significant amount of dis- and misinformation circulating in our changing media environment.

Audience perspectives on fake news

brought up the issue in 8 focus groups conducted across the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Finland. We asked participants to define the concept and tell us what “fake news” meant for them. It is important to note that the purpose of qualitative research like this is depth and nuance, and that the findings will always reflect the particular respondents and cannot be taken to represent the population as a whole. Our focus group participants do not all agree with one another, and not everyone will in turn agree with them. It is also important to underline that the term “fake news” generated a lot more discussion in the United Kingdom and especially the United States than in Spain and Finland. Nonetheless, some clear patterns can be identified.

Figure 1. Audience perspectives on fake news

Based on our focus groups, we can identify different types of content that people associate with the term “fake news.” Most focus group participants recognize that the term has been weaponized by critics of the news media as well as by critics of platform companies. They also clearly distinguish between satire and more maligns forms of fabrication. But that still leaves a wide and diverse range of content that many think of as fake news, including poor journalism, political propaganda, some forms of advertising, as well as false and fabricated content more narrowly. These latter categories are seen as different from journalism in general primarily by degree; for audiences, the difference between fake news and real news is not absolute but gradual. The main categories in popular understandings of fake news can be arrayed as in figure 1, above.

First, people see the difference between fake news and real news as one of degree

In contrast to academics and others who define the problem as fabricated stories masquerading as legitimate news reports, produced either for profit or for political ends, most focus group participants see fake news as a broad and diverse category and one that is separated from other forms of news primarily by degree. The difference between fake news and real news is not black and white. Take these responses from one of our London focus groups:

Moderator: What does “fake news” mean to you?

M1: Made up stories.

F: Do you believe everything that you hear and

see and read? I’m sure some of it is made up.

M2: It’s a spectrum isn’t it?

M3: There’s been fake news for years hasn’t there?

The notion of a “spectrum” and the view that fake news is an age-old problem was expressed elsewhere too, including in Finland, where the term otherwise generated little discussion. Asked about fake news, one focus group participant in Helsinki offered this definition: “News that don’t have a factual basis? Coloured, leaning, biased”, and then continued “But then again, is any media organization truly objective? It is a question of scale really.”

When asked to define fake news, focus group participants offer a range of definitions as well as a range of ways in which they see others (including other ordinary people as well as news media and politicians) using the term.

There are two meanings okay; there is one meaning where it is news that has the opposite aim of real news which is to inform. It is news that does not tell the truth which aims to misinform. Then it is also being used to describe real news that disagrees politically with the person’s [own views.]

The simplest definition of fake news was offered by a woman in one of our New York City focus groups, who called it simply “misinformation.” But in practice, most focus group participants say it is hard to distinguish clearly between information and misinformation, and that they rely on their own critical faculties to make sense of what they come across. They understand that this can be a subjective judgment. Another woman in the same New York focus group said that for her, “fake news” is “news that you don’t believe is real.” She continued, “this guy has got one story, [another] has got the other story, you decide which one is fake and you decide which one is real.” As one participant in one of our London group underlined: “you need to check”.

In the course of the group discussions, people generally pointed to what have been called “source cues” (brands they trust) and “social cues” (people they trust) used to verify information, saying they rely on friends and family, trusted news media, and their own (online) research. (This is in line with what has been found by researchers like Messing and Westwood 2014 and Tandoc et al 2017.) But this can be demanding work, and they also report that they often ignore the problem if it does not seem worth the trouble to check up on a specific piece of dubious information.

Second, the main forms of fake news people identify are poor journalism, political propaganda, and some forms of advertising

When asked to provide examples of what they think of as fake news, focus group participants point to instances of what they see as poor journalism (often from established media organizations), to propaganda from political actors they don’t trust (whether domestic or international), various forms of advertising and sponsored content they come across online, and only rarely to false content masquerading as news. While relatively large-scale commercial or state-backed operations producing fabricated news stories account for much of what is narrowly defined as false news, people see a much broader fake news problem that implicates journalists and domestic politicians too.

Focus group participants associate poor journalism with sensationalized or unreliable reporting, especially in areas such as celebrity, health, and sports coverage. “There is a lot of celebrity fake news for instance… Oh Jennifer Aniston has a new husband. You can research it through twenty different sites and they all could be regurgitating news furthering the lie”, says one US participant. In Spain, a participant says “for health, or sport, which is what I like, the majority is lies. There it has to do with the sector in general.”

Propaganda meanwhile is associated with politicians who lie outright or try to spin stories beyond belief. President Trump is brought up frequently, and not only in the US. “Donald Trump, you know… at his inauguration he is saying so many thousands and thousands and then you see actual pictures and then he said the other day that he had the most electoral votes ever and a reporter said to him he had three hundred and four and he said but Obama had three sixty-five.” But propaganda is also associated with how journalists cover politics. People consider what they see as partisan news coverage to be a kind of misinformation because of what it omits or how it presents facts. In Spain, one focus group participant goes beyond this and says “[news media] put things in people’s mouths that haven’t happened in reality, they invent things that haven’t happened, that haven’t occurred… There are some more reliable media outlets but in general [fake news] is in everything… That makes me reject the media.”

Many focus group participants also see many kinds of potentially misleading advertising, including some pop-up ads, some forms of sponsored content, and some forms of “around the web” links offered through Outbrain or Taboola, as examples of fake news.

F1: You get those ridiculous fake news stories like the pop-up ads because when it is free news

they are relying on ads sales.

Moderator: Are you nodding to that? Fake news what do you mean there?

F2:Like when you scroll down far enough and it is like “look at how these twelve child celebrities turned out” and they are just ridiculous pictures.

Finally, fake news is also associated with false news narrowly defined; the kinds peddled by for-profit actors or as part of misinformation campaigns. As one participant explained, “It’s there to either click to sell advertising space and you can make up what you want or you can use it to promote propaganda.” (Of course, part of the problem is that false news that succeeds in deceiving people will not be recognized as such.)

In contrast to poor journalism, propaganda, some forms of advertising and outright false news, several focus groups participants explicitly argued that for example satire—even if strictly speaking untrue—is not fake news. As one focus group participant put it: “I mean there is fake news and then there is satirical news which is technically fake news but it is awfully amusing.”

Third, people associate publishers, platforms, and politicians with fake news but also see trusted news outlets as a potential corrective

Fake news is thus clearly a term that resonates with people because it speaks to a long-running scepticism of journalists, news media, and politicians. But it is also clear that the term is gaining traction because of the kinds of things people come across online. This came up again and again in focus groups, for example in our discussions in New York, where one participants said “I notice it a lot, especially on social media and then people will say this happened and you are like did it really? You want to see if it really did. There is a lot of fake news.” Another participant elaborated: “There is no vetting on the internet, so anyone can post anything, at least if they publish a newspaper, they are supposedly supposed to be factual.”12 While rarely directly blamed on platform companies, the proliferation of misinformation is often associated with platform products and services, especially sharing on social media. One woman in one of our London focus groups says “I think like on my Facebook more people are sharing news things than they were before and there seems to be more fake than there was before, it seems to have changed.”

As is clear from the sections above, people have very mixed views of the role of news media in the spread of fake news. They often have a dim view of tabloid media and of partisan outlets that they disagree with politically. But many identify specific organizations they would turn to if they need credible information. One participant in one of our London groups said: “The Times [has] a paywall and the reason they do it is that it costs a lot of bloody money to verify these facts, so there is no fake news here. Then whatever out there in the wild is feral news, fake news.” In the US, people repeatedly mention CNN and the New York Times, in the UK the BBC, in Spain El Pais, and in Finland the Helsingin Sanomat. But it is also clear that there is not a consensus on which outlets to trust. Other participants dispute the trustworthiness of these established brands, and favour alternatives that some might see as very partisan. Some in the United States see the New York Times as biased and Fox News as more balanced, for example.

Fourth, people are aware of the fake news discussion and see the term “fake news” in part as a politicized buzzword

Most focus group participants, especially in the US and the UK, are aware of discussions around fake news and have views on the issue. It is clear that this awareness is in part driven by their own personal media experiences, as discussed above. But awareness is heightened by the very public debate around the issue, driven both by news coverage of online misinformation and by prominent politicians using the term to attack journalism. As one focus group participant in New York said with reference to Trump’s frequent use of the term on Twitter, “fake news is a big buzzword that is being thrown around by people like they will say “oh CNN fake news or alternative facts”.” Political actors attacking the media as “fake news” are thus leveraging a very real frustration in many quarters, but people are also aware that the term is increasingly weaponized.

The low-trust context of the fake news discussion

Both our focus group data and our survey data provides a powerful reminder that the fake news debate plays out against a backdrop of low trust in many public and civic institutions.

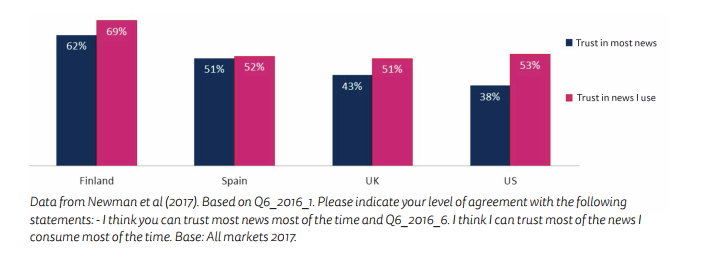

Figure 2 – Trust in most news versus trust in my news

This is arguably one of the reasons the term has resonated so strongly with many people, whether used to criticize platform companies, publishers, or powerful politicians who lie. For instance, looking at the four countries we cover here, our survey data document that less than half of online news users in the US and the UK think you can trust most of the news most of the time. While the figures are higher in Spain and in Finland, very large parts of the population still have limited trust in news in general, and—strikingly—only somewhat higher trust in the news that they themselves use (see figure 2). In three of the four countries, nearly half of the population don’t express trust even in the news they consume.

Comparing people’s perceptions of news media and social media reveals a similar pattern. Asked whether, respectively, news media and social media do a good job in helping users distinguish between fact and fiction, people express only limited confidence in either (Newman et al 2017). Most notably, confidence in news media and confidence in social media seem to be related and not opposed: Low trust in one is rarely accompanied by high trust in another. Instead, the general attitude is one that has elsewhere been characterized as “generalized scepticism” (Fletcher and Nielsen 2017).

This attitude also comes through clearly in our focus groups, where participants in country after country express their scepticism of both platforms and publishers. In the US, one participant says “I kind of like to read stuff on Facebook but I just, I don’t even, if it is newsworthy on Facebook I won’t even open it up, I won’t even look into it.” Both our surveys and focus groups show clearly that people do not uncritically accept all the information they come across via social media and other platforms. Similarly, another participant speaks darkly of his eroding confidence in news media: “I think it has changed a lot. I used to rely a lot more on the news, I thought it was correct but nowadays…” In Finland, when asked how fake news influence people’s overall attitude towards news, one focus group participant says “[It] corrodes the appreciation for other news, if we can’t tell them apart especially” and another adds “people become sceptical of all news.”

The situation that platform companies, publishers, and politicians alike face is neatly captured by another participant: “There’s that thing about reputation isn’t it? It takes forever to build and a second to lose.”

Conclusion

The discussion around fake news has only intensified after the 2016 US presidential election, with similar discussions playing out around the role of platforms, politicians, and news media in different countries all over the world. Some have suggested that it is time to retire the term “fake news” because it is so imprecise and is used by politicians and others to attack news media and platform companies (Sullivan 2017). Our research suggests that won’t happen easily. While it is true that the term “fake news” is frequently used instrumentally for political advantage—a fact that ordinary people often recognize—it has also become part of the vernacular that helps people express their frustration with the media environment, because it resonates with their experience of coming across many different kinds of misinformation, especially online, and because it is used actively by critics of both news media and platforms.

When it comes to fake news, this RISJ factsheet provides both qualitative and quantitative evidence that most people do not draw the line between fake news and other kinds of news in simple ways, and do not always draw it the way journalists, technology companies, and policymakers think. What you think fake news is depends on what you think of news more broadly. And there is no objective (or even intersubjective) agreement on what good news look like, only a distaste for content that is designed to deceive—and no consensus on exactly what that looks like or who the main purveyors are. Fake news, many people say, is news you don’t believe and that includes news from some established news media, and the statements of politicians who lie, spin, and exaggerate. This bottom-up perspective on fake news has largely been missing from discussions among academics, journalists, media executives, and policymakers. Our findings suggest that, from an audience perspective, the fake news problem is only in part about fabricated news reports, and reflects a deeper discontent with many public sources of information, including news media and politicians as well as platform companies. It is clear that for ordinary news users, as indeed for journalists, politicians, and researchers, the world is not neatly divided into truth and falsehood (Graves 2016).

This underscores the difficulty of finding simple solutions or clear culprits in discussions of fake news. Developing mechanisms to ban, flag, or delete false news reports and other kinds of malicious misinformation from the media environment may be a necessary step. But cracking down on for example hyperpartisan outlets might satisfy some people while further aggravating many others. Most people have specific news media that they trust, and particular strategies for navigating the contemporary information environment. But the context for their attitudes about that environment is one of low trust in general and little agreement on who are trustworthy. From audiences’ perspectives, the problem of fake news is not narrowly confined to false news—it also concerns poor journalism, political propaganda, and misleading forms of advertising and sponsored content. If we are to make progress in addressing this, journalists, news media, and tech companies need to confront the fact the people see fake news as a broad problem and blame all of them for it. Addressing that will must involve building—or rebuilding—people’s confidence in institutions many do not trust.

About the authors

Rasmus Kleis Nielsen is Director of Research at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and Professor of Political Communication at the University of Oxford.

Lucas Graves is Senior Research Fellow at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford