Authors: Tom Nicholls, Nabeelah Shabbir and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen

Executive Summary

In this report, we analyse a sample of seven internationally oriented digital-born news media on the basis of interviews with senior editors and executives. We examine the basic business, distribution, and editorial strategies of long-established players like HuffPost and Mashable, newer entrants like Quartz, and recently launched European enterprises like De Correspondent (from the Netherlands) and Brut (from France). We show how these media, often on the basis of venture capital funding or other deep-pocket backers, have pursued an expansive global strategy oriented towards securing audience growth first, expecting to generate profits later from advertising. All pursue an expansionist strategy that at its most basic is what we call a ‘US-plus’ model, targeting the largest media market amongst high-income democracies, the United States, plus one or more additional markets (ranging from two or three at its most focused to more than a dozen in a few cases), generally concentrating on high-income democracies where Internet use is widespread and digital media capture a large share of overall advertising.

Our three main findings are as follows.

First, several of the internationally oriented digital born news media have used a combination of on-site and off-site distribution, often involving aggressive search engine optimisation and social media promotion coupled with content that is free at the point of consumption, to build large audiences across multiple countries, generally on the basis of a much leaner organisation than most legacy media.

Second, the business model of most internationally oriented digital-born news media is based on digital display advertising, an increasingly challenging market due to the move to mobile, the rise of programmatic, competition from large platform companies, and the spread of ad-blockers. Unlike in domestic digital-born news media and among newspapers, pay or member models are rare and most continue to pursue advertising revenues (including increasingly through sponsored content and video). So far, most internationally oriented digital-born news media remain in investment and growth mode, and have not been consistently profitable. In some cases, investors and owners seems to be losing patience and are pushing for cost cutting as a way of turning a profit.

Third, while expansion across multiple markets has enabled internationally oriented digital-born news media to expand their audience, this expansion also comes with challenges, and involves dealing with the tension between globalising and localising pressures, decisions about whether to partner or go alone, maintaining consistency in branding and tone across multiple editions and languages catering to sometimes very different markets, and the challenges of coordinating global newsrooms – challenges to which several of our case organisations are in turn developing technological responses.

In pursuit of their global expansion, internationally oriented digital-born news media have to handle tensions between centralising and decentralising tendencies, and make choices about whether they expand on the basis of a relatively uniform voice or pursue a multi-local strategy with more autonomous and adapted national editions. This involves decisions about content and editorial priorities, but also about investments in audience engagement, building relationships, and managing communities. It also involves investing in technology and technological expertise, both to pursue platform reach (while managing platform risk) and to develop in-house tools, including tools for automated discovery (like Mashable’s tool ‘Velocity’ for story detection), automated curation (such as Blendle’s AI system for article selection), and automated translation (e.g. Vice’s integration of Google Translate into their Content Management System).

Despite their often wide reach, all our cases see themselves as niche publishers, whether upmarket or popular, no one sees themselves as comprehensive or for all audiences. In terms of content, they compete with both legacy incumbents and domestic digital-born news media. The challenges they face are fundamentally similar – how to develop editorial, distribution, and funding strategies that enable a sustainable, perhaps even profitable, production of quality news in an increasingly digital, mobile, and platform-dominated media environment.

In this sense, it is clear that they are not so much disrupting legacy news media and other domestic players as they are facing many of the same challenges and opportunities. The overall digital news situation resembles a digital content bubble where most providers continue to operate at a loss – in the case of legacy media sustained by profits from offline operations and in the case of digital-born organisations sustained by investors with varying degrees of patience. This bubble will eventually burst unless more diverse and sustainable business models are found. Where most internationally oriented digital-born news media seem most exposed is in their reliance on one main revenue stream in digital advertising and in terms of the platform risk that comes with the dependence on especially Facebook. Where they seem strongest is when they face those challenges with a leaner organisation and a clearer strategic focus plus editorial identity than most legacy media, and make more effective use of technology, both in terms of platforms like search and social and in terms of in-house tools for automating and enabling work.

Introduction

Beginning with the Huffington Post (now HuffPost) and others like it, the last decade has seen a number of often US-based digital-born news media expand globally, opening editorial offices in multiple countries, developing targeted websites and social media strategies for a range of different target markets, and often adding new language editions to their original English language offerings. HuffPost, for example, opened its Canadian and UK editions in 2011, and in 2012 it launched Le Huffington Post in partnership with Le Monde in France. It is now active in 17 countries. BuzzFeed operates 11 editions and Vice has a presence in more than 30 markets.

These internationally oriented digital-born news media are pursuing a different strategy than their domestically oriented counterparts, a strategy generally premised on aggressive expansion, normally fuelled by either venture capital or deep-pocket investors, and based on the expectation that profitability will eventually follow once the audience has grown large enough. There has been significant investment in digital-born media, especially in the United States – one research firm estimates $15.6 billion in venture capital funding over the past three years (Moses, 2017). Legacy media companies have also invested and acquired significant stakes in several digital born news media. Whether owned by larger media conglomerates (as HuffPost is after Verizon acquired AOL and Business Insider is after being acquired by Axel Springer) or operating as independent enterprises (like BuzzFeed and Vice), in terms of their ability to invest in growth, these internationally oriented digital-born news media are as different from their domestically oriented digital-born counterparts as they are from legacy media.

In this report, we analyse the business, distribution, and editorial strategies of a sample of internationally oriented digital born news media including long-established players like HuffPost and Mashable, newer entrants like Quartz, and recently launched European enterprises like De Correspondent (from the Netherlands) and Brut (from France). All pursue an expansionist strategy that at its most basic is what we call a ‘US-plus’ model, targeting the largest media market amongst high-income democracies, the United States, plus one or more additional markets (ranging from two or three at its most focused to more than a dozen in a few cases), often concentrating on high-income democracies where internet use is widespread and digital media capture a large share of overall advertising. Whether they aim to cater to one specific niche audience or cater to a wider audience, they are pursuing international scale to grow their business and sustain their journalism.

This means that all these digital-born news organisations are far more international and have much wider multinational audiences than the vast majority of legacy news media, even though they are often much smaller in terms of editorial resources and total revenues. Most news media, whether legacy or digital-born, focus on one local, regional, or national market. Not so with the organisations we analyse here. The most expansive, like HuffPost, have more editions across the globe than even the most internationally oriented newspaper companies, well ahead of papers like the Guardian, the New York Times, or the Wall Street Journal (all of whom are larger in terms of editorial resources and revenues). It has a presence in more different countries (17) than all but the biggest international broadcasters like the BBC and CNN.

The report is based on interviews with senior editors and executives at seven internationally oriented digital-born news media, namely Brut, Business Insider, De Correspondent, HuffPost, Mashable, Quartz, and Vice (a full list of interviewees is given in the Appendix). The sample represents a mix of long-established titles like HuffPost and Mashable and more recent entrants, and include both organisations focusing on a few target markets and ones with many more national editions. The cases covered are all expanding across multiple markets, and all share a commitment to at least some coverage of news and current affairs (in addition to lifestyle, culture, etc.). One case, Vice, is not strictly speaking a digital-born organisation as it evolved out of a Canadian print magazine, but since relocating its headquarters to the United States, it has invested so heavily in digital media and international expansion that it makes sense to include it here. We approached several other organisations, including BuzzFeed, but not all those approached were willing to talk on the record.

Like domestically oriented digital-born news media from countries across the world, all these cases are editorially led content companies at least as much as they are technology companies, more clearly rooted in a commitment to journalism than other interesting new initiatives in digital news, such as content aggregators focused on developing pay-per-article systems (like Blendle, also interviewed for this report) or driving mobile discovery (like Upday) (Nicholls et al., 2016). Like other digital-born news media studied by others, they are both technology-oriented (digital-born) and journalism oriented (news media) (see e.g. Tandoc, 2017; Usher, 2017).

We have three main findings.

First, several of the internationally oriented digital born news media have used a combination of on-site and off-site distribution, often involving aggressive search engine optimisation and social media promotion coupled with content that is free at the point of consumption to build large audiences across multiple countries, generally on the basis of a much leaner organisation than most legacy media.

Second, the business model of most internationally oriented digital-born news media is based on digital display advertising, an increasingly challenging market due to the move to mobile, the rise of programmatic, competition from large platform companies, and the spread of ad-blockers. Unlike in domestic digital-born news media and among newspapers, pay or member models are rare and most continue to pursue advertising revenues (including increasingly through sponsored content and video). So far, most internationally oriented digital-born news media remain in investment and growth mode, and have not been consistently profitable. In some cases, investors and owners seems to be losing patience and are pushing for cost cutting as a way of turning a profit.

Third, while expansion across multiple markets has enabled internationally oriented digital-born news media to expand their audience, this expansion also comes with challenges, and involves dealing with the tension between globalising and localising pressures, decisions about whether to partner or go alone, maintaining consistency in branding and tone across multiple editions and languages catering to sometimes very different markets, and the challenges of co-ordinating global newsrooms – challenges to which several of our case organisations are in turn developing technological responses.

Below, we briefly introduce the seven case organisations we cover, before turning to examine the business models behind the pursuit of international scale, the distribution strategies and embrace of platforms used to build audience reach, how brand licensing and other strategies facilitate global expansion, and finally how our case organisations think about editorial strategy and brand identity across countries.

Cases

BRUT

It is impossible to access videos on Brut’s homepage; it exists on distributed platforms only, of which Facebook is the most prominent partner. Brut (meaning ‘raw’) say they are the firstmedia offering to be ‘100% digital, 100% video’. Launched during the French presidential election in October 2016, its 90-second news videos on politics and society garner millions of views. The site has generated hundreds of millions of video views already, primarily via Facebook (Cobben, 2017), and report an average of 430,000 views per video posted (Facebook, 2017). Created by former late-night television executives, who have self-funded and raised venture capital, expansion has been a priority. Brut India launched with an editor in Paris. Brut US is currently in soft launch, led by former CNN and Upworthy journalists in New York.

BUSINESS INSIDER

Launched in 2009, and bought by Axel Springer in 2015 for about $450m, Business Insider is published in 16 countries and across seven languages. It reports 120 million monthly unique users, with lifestyle and tech spin-off sites. There are over 10 million followers across social platforms, and a staff of 200 worldwide. It has set up Insider Shows to create more long-form videos.

DE CORRESPONDENT

Founded by two former newspaper journalists, De Correspondent launched with a world record – it crowdfunded one million euros in just over a week. Whilst it still crowdsources its beats, working closely with readers, the Dutch news start-up has established a member based business. Over 50,000 members currently pay monthly or annually. It is currently part of a year of research around membership models at NYU, with media professor Jay Rosen as ‘ambassador’, ahead of a US launch in 2018.

HUFFPOST

Launched as the Huffington Post in 2005 and acquired by AOL in 2011 for about $315m, with AOL in turn acquired by Verizon in 2015, the site is now formally ‘HuffPost’ and led by Lydia Polgreen, formerly of the NYT. Under the new leadership, a new international director is reworking its global footprint of 17 editions. The Brazilian, Canadian, and UK editions are owned by the group and the other editions are local partnerships with heavyweight media outfits, such as Prisa (owner of El País) in Spain or Le Monde in France.

MASHABLE

Founded in 2005 (and a couple of months before HuffPost), the digital news site started as a blog in Scotland. Based in New York, the technology site does some news as well as culture and entertainment. It has a joint venture in Spanish with Telemundo, and major offices in Australia, Singapore, and the UK. In 2014, Mashable UK was launched, followed in March 2016 by ‘Mashable with France 24’; this is in partnership with a French public broadcaster. In November 2017, the site was sold to the trade publisher Ziff Davis for $50 million, significantly less than the $250 million valuation it received in an investment round in 2016 (Sharma and Alpert, 2017).

QUARTZ

Owned by The Atlantic Media Company, Quartz aims to be a guide to the global new economy. The online business site has offices in the UK and Hong Kong, and journalists in Africa, as well as a partnership in India. Quartz recently celebrated its fifth birthday with the release of its first book, an expansion of its lifestyle and work verticals. It reports an average monthly global reach of almost 20 million, with 40 percent of readers coming from outside the United States.

VICE

Originally a print magazine in Montreal 25 years ago, Vice is today clearly a digital-first company. Headquartered in New York, the global youth and lifestyle media company has journalists in over 50 countries worldwide, most recently expanding into India and the Middle East. Vice focuses on local politics, music, culture, on the ground reporting, and a series of verticals and offshoots – such as Vice News. A multifaceted organisation, Vice’s focus on longform documentaries continues, with a weekly news show with US cable network HBO, the launch of a feature-length film on Netflix, and a television channel called ‘Viceland’ with local media partnerships, and is moving into bespoke mobile video content.

Business Models and the Pursuit of International Scale

Almost all of the internationally oriented digital-born news media covered here base their business primarily on advertising. The basic idea behind their expansion is simple – by expanding their audience globally, often through relatively small investments in individual target markets combined with leveraging content and technology developed for the large US market, fixed costs can be amortised across more readers and more revenues can be generated to invest in better content and to return a profit. Expansion is thus both an editorial ambition and a business opportunity.

For some, traditional website display advertising sold direct to advertisers is at the core of their business, whereas others are increasingly focusing on a combination of programmatic advertising, revenue-sharing from content published via various social media, sponsored content, and video advertising. The focus on advertising, in turn, means that most of these organisations are pursuing scale and seek audience growth both onsite and offsite, via web, apps, search, and various social media. The premise in most cases is a recipe of growth-first-profits-later. (How much later varies and depends on investors’ or owners’ patience.) De Correspondent, the Dutch site built around a membership model, currently expanding into the United States, is the only exception to the focus on advertising.

While this business model and the distribution strategies designed around it have enabled and underpinned the expansion of internationally oriented digital-born news media and helped them reach wide audiences, it is also clear that it faces a number of challenges similar to those facing legacy news media who have based their digital operations on freely accessible news monetised through advertising (see e.g. Cornia et al., 2016).

Jean-Christophe Potocki, general manager at HuffPost France, spoke clearly about the centrality of advertising and the importance of getting it right:

It’s all very well and good to try to diversify, which is what we’re going to do as well, but if we don’t fight this battle, given our model, we’re dead. Diversification is to provide extra, but our model is advertising and we need to fight it directly

The competitive pressures in terms of capturing people’s attention and attracting advertisers are not only from incumbent legacy media or other digital-born news media, but also from large platform companies. As Jason Karaian, global finance and economics editor at Quartz put it, ‘We are competing not just with other news outlets but with your friends on Twitter and your family on Facebook and random ex-co-workers on LinkedIn.’

The main challenges facing advertising-funded digital news media are:

• the low average revenues per user, especially with the move from desktop to mobile access accelerating;

• the rise of programmatic advertising, widely seen as depressing CPMs for display advertising;

• the dominant role of large technology companies like Google and Facebook that attract a large share of online advertising;

• the growing use of ad-blockers, especially on personal computers.

These four challenges mean that many organisations feel they have to continuously grow their audience to continue to increase their revenues, even as the overall digital advertising market is growing. Some interviewees see revenue from content published via various social media, sponsored content and video as important new opportunities, but many caution against expecting too much. Sebastian Matthes, editor-in-chief of HuffPost Germany stated that ‘what we have seen in Germany this year is peak video’, and foresaw a general retrenchment as video advertising revenue failed to grow sufficiently to fund expanding video teams. Most further report that their international expansion often demonstrates how variable advertising rates are across countries, with CPMs often lower outside the US and audiences harder to monetise through direct sales, leading more inventory to be sold through programmatic networks.

The CEO of a major US-based digital-born news media that has chosen not to pursue international expansion says the risk is that the risk is one builds ‘vanity reach’, incrementally increasing the total number of monthly users but with little depth and breadth in individual markets and limited opportunities for meaningful monetization to ensure a reasonable return on investment. A few years ago, HuffPost admitted that though overseas markets contribute half its global audience, its many international editions generate only 10 to 20 percent of total revenue (Moses, 2014).

In contrast to the newspaper industry, where more and more titles are developing pay models, and in contrast to domestically oriented digital-born news media, where some are trying subscription models and others membership models, very few internationally oriented digital-born news media pursue pay models (Cornia et al., 2017). Business Insider runs an ‘Intelligence’ product, selling detailed business research at high prices, is trialling an ad-free subscription model with some unique content, and (like several of the other news organisations we studied both this year and last) collects some affiliated marketing revenue through purchase links on products discussed in some verticals. But the main outlier is De Correspondent, which launched in the Netherlands with crowdfunding and since then has operated on a membership model with a paywall. In doing so, De Correspondent is trying to go behind the standard model of international digital media – to rely on advertising – and pursuing an approach similar to that of a number of other pioneering European digital-born news media, including MediaPart and El Diario (Nicholls et al., 2016).

De Correspondent are clear that they see their approach, with the emphasis on convincing people to become paying members on the basis of a limited output of high-quality content combined with an emphasis on audience engagement, as very different from that of most other digital-born and legacy news media. Ernst-Jan Pfauth, founder and publisher, put it like this: ‘You can’t have a membership without actually asking people to contribute something else than money. There has to be this relationship.’ He talked about De Correspondent reporters sometimes spending half their working week having conversations with readers, building trust and building relationships for future reporting.

As they begin their entry into the US market, they are engaged in a major piece of research to explore how membership might work in a different context. This research, the Membership Puzzle Project, is being undertaken together with Jay Rosen at New York University. Emily Goligoski, research director at the Membership Puzzle Project, is convinced that membership-based models for funding online journalism are viable: ‘Understanding how news site membership fits in with supporters’ own mental models is imperative. What are your prospective members’ needs? Motivations? What won’t they tolerate? Do they think of your site’s work as cause-driven, charitable, or something else?’ She adds: ‘There is a great deal that news can learn from other for-profit and non-profit organisations about pricing strategies and marketing authentically.’ As De Correspondent has not yet launched in the US, the long-term success of this model is still unclear, but others are watching with interest.

Distribution Strategies and the Embrace of Platforms

At the core of most of the cases covered here is a website and in some cases an app, basic tools to start an international expansion premised on the relative absence of geographic and distribution related barriers to entry on the Internet. A website is a cheaper starting point for international expansion than a printing plant, broadcast licence, or satellite or cable channel. In addition to focusing on producing compelling content and standing out from both legacy and digital-born competitors, internationally oriented digital-born news media have also often been pioneers in leveraging the opportunities afforded by large platform companies like Google and Facebook through the development of search engine optimisation and social media promotion strategies, where sites like HuffPost and BuzzFeed are widely recognized as pioneers. All pursue several supplementary ways of reaching audiences both on-site and off-site, but most are increasingly reliant on Facebook – especially a full distributed brand like Brut which does not use a website at all, but focuses entirely on video distributed via social media and has in less than a year established itself as one of the most prominent digital-born news media in France (Majó-Vázquez et al., 2017).

The reliance on distributed discovery and distributed content delivered off-site as well as the continued importance (for most) of on-site delivery via websites and apps present internationally

oriented digital-born news media with some of the same challenges and opportunities that other publishers face in dealing with platform companies like Google and Facebook (Nielsen and Ganter, 2017). Search and a variety of social media are often key to reach, and most of our cases are pursuing scale, and therefore need the reach that platforms can help deliver. But this requires investment, and involves risks that platform priorities change or audiences come to expect free off-site access to all content. And it can sometimes be hard to realise an immediate return on the investments required to make full use of platform opportunities. Much depend on the platform architecture, its user base, and the various forms of monetisation it supports. Facebook is the most important platform for several organisations, and while sometimes regarded with some trepidation due to how dependent some feel they are on this popular social media site, and the concern that it sometimes changes its priorities in ways felt by all who rely on it, it is also seen as an invaluable source of reach and referrals. Snapchat Discover is an interesting counterpoint, which many are very interested in because it is seen as potentially key to reaching younger audiences, while also being harder to work with. As Jim Edwards, founding editor and editor-in chief of Business Insider UK, explains:

Snapchat Discover is difficult. It requires a lot of resources. It’s not obvious what people want on there, and the reward, the return on investment for doing that is also not obvious. With Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, it’s easier. They have an ad model. You can expand it very quickly. With Snapchat, it’s just a bit harder.

To make full use of different platforms, internationally oriented digital-born news media tailor content and promotional strategies to each major platform, with teams or individuals responsible for adjusting to the different formats and forms of discovery enabled by each. While this helps improve performance, the tailored approach also requires resources and thus comes at a cost. Again, interviewees frequently make clear that it is rarely easy to work with the platforms they depend on. Apple News was repeatedly held up as an example of this, potentially very important, but not a straightforward platform to work on commercially. Jack Riley, director commercial and audience development, HuffPost UK, observed that ‘Apple are very prescriptive about what we can do’, adding that while ‘some publishers pulled out of it’, HuffPost UK feel they have, with work, managed to do very well with it.

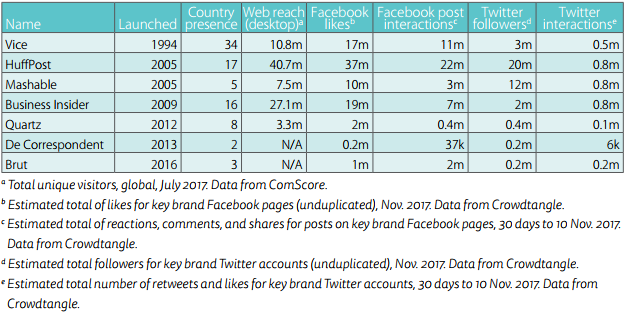

A snapshot overview of website and social media audience reach is provided in Table 1. There is a fairly sharp difference in reach between the more established companies operating in multiple markets (Vice, HuffPost, Mashable, and Business Insider) and the newer media currently expanding (Quartz, De Correspondent, and Brut). The relative contribution of platform interactions and direct website traffic is variable, with Vice, Mashable, and Brut being particularly dependent on social reach, which may reflect their editorial aims and target audience as well as their own distribution priorities. The purest approach to platform distribution we see is from Brut, who use social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Daily motion, Instagram, and Snapchat) as their sole means of distribution and do not publish news on their website at all. This is an emphasis on off-site audiences and distributed reach also seen in BuzzFeed and in cases like AJ+, Diply, and NowThisNews.

The major consequence of organisations using platform distribution as the key building block for

expanding reach is that they are then dependent on the platforms for their continuing success.

All interviewees are aware that what platforms give, they can take away. Recent changes to Facebook’s NewsFeed, seen as prioritising content from friends and family above those from media pages, have highlighted the potential challenges. Even so, no one wants to miss out on the reach that platforms can help deliver. It is also clear that the audience built through heavy reliance on search engine optimisation and various forms of social media promotion and publishing is sometimes a mile wide and an inch deep, with little in terms of a loyal, engaged, returning audience. (This problem is not unique to digital-born news media but faced by some legacy brands too, see e.g. Newman and Kalogeropoulos, 2017.)

Table 1: Website, Facebook, and Twitter reach

Global Expansion and Brand Licensing

All the internationally oriented digital-born news media covered here are expanding beyond their home market. The number of countries they target varies greatly. Some, like De Correspondent and Quartz, are focused on a few, while Vice has 34 editions. For the US-based brands, one motivation for global expansion is a sense that their domestic market is saturated. As Jim Edwards, Business Insider UK, noted:

It’s hard to see how the American edition, which is also obviously the biggest one, is going to get any bigger – particularly inside the US. In some months it reaches 100 million people. There’s only about 320 million Americans. It’s like, ‘How many more Americans can you put on this thing?’

The choice of countries in which to expand is also critical, and can depend on the local culture as well as the scale of commercial opportunities available. The basic approach, whether coming out of America or out of Europe as Brut and De Correspondent do, is what we have called a ‘USplus’ model that combines a focus on the single largest media market amongst high income democracies with one or more additional markets, typically high-income democracies where Internet use is widespread and digital media capture a large share of overall advertising (though India is also a key target market for several brands, including HuffPost, Quartz, and Vice).

Ernst-Jan Pfauth, founder and publisher at De Correspondent, was clear about why the US was their first target and not somewhere closer to home:

We decided that we wanted to launch an English version of De Correspondent with the US as a home market. Our goal is to become a global media, but we picked the US because it’s big, we have a good network there, and good partners. We know the market better than, for example, the UK market. Which is ironic, because it’s close by.

Brut offered similar reasons for focusing on the US market as an early target, though interestingly, its third market is a large one rather than a wealthy one – India, where the net number of Internet users is estimated to be growing by about 250,000 every day right now due to the spread of cheap smartphones and a price war on mobile data (see e.g. Aneez et al., 2016). Others, like HuffPost and Vice, are also active in India. Hosi Simon, global general manager at Vice, was clear as to why:

India, I’ve been very, very bullish on in our expansion. I’m not smart for saying that. Look at Facebook, look at Google, everyone looks at that next wave of the Internet. That’s where the next billion people will come online. They will come from Indonesia, they will come from India, they will come from Southeast Asia.

Several of our case organisations have expanded into new markets by licensing their brand. This can be quite a traditional partnership – Business Insider Italy with La Repubblica – and in some parts, complex. Prisma runs Business Insider France, but is owned by a competitor (Bertelsmann) to Axel Springer, the owner of Business Insider. Whilst this makes Business Insider France an independent media company, they are still beholden to the brand’s values, explains MarieCatherine Beuth, editor-in-chief.

The choice between licensing and direct expansion is a complex one, with elements of speed, revenue, and control. Jim Edwards from Business Insider UK explains:

So, after we did the first few licenses, we thought about ‘Well, maybe we should open in Britain, because it’s the second-biggest English-speaking market’ and we thought ‘Well, if you license you get half the revenue. If we own it and run it ourselves we get the full revenue.’

HuffPost was clear that the various partnership editions had a high degree of autonomy, though not complete freedom to use the brand for something inappropriate (a point echoed by other interviewees). Louise Roug, international director, said:

On one hand, you want to further the individuality of the market. But on the other hand, you obviously want to have some kind of cohesion. So there’s always a bit of a tension there that is expressed in different ways.

A key advantage of licensing and partnerships is speed; the local partner organisation can provide local expertise, capital, and existing commercial relationships to help jump-start a new edition. Hosi Simon, global general manager at Vice, put it this way:

Once you do big market entry joint venture with some of the most respected media companies in the world, it helps us accelerate in this moment we believe we have. We could have done India by ourselves, ultimately, but it would take us five years. With a partner like Times of India, it’ll take much less.

Partnership benefits can flow both ways. Steven Jambot, deputy editor at Mashable France, described how Mashable helped their partner France 24 work with Facebook Live: ‘we showed the rest of the newsroom how to do it and everyone said “Okay, that’s fine. We should do the same.” We were a kind of startup.’ Whereas the digital-born brand may thus accelerate its international expansion, pursuing the reach and scale needed to generate significant advertising revenues, a legacy media partner may in turn be looking for learning and knowledge transfer.

The expansion is not always a one-way street and media sometimes retrench, though this is rarely at the centre of the story they then tell about their trajectory. Business Insider has closed two editions, and the HuffPost has reportedly both ended its previous collaboration with the Times of India and scaled back its previously ambitious public plans for further expansion (Shashidhar, 2017). Its goal of being in 50 markets by 2020 – stated in 2015 by Arianna Huffington before the site was sold to AOL – no longer looks like a priority. HuffPost also cut 39 jobs in the summer of 2017. It is not the only internationally-oriented digital-born news organisation revisiting its investment mode and reining in costs. Mashable made significant cuts in 2016 (Perlberg, 2017), and Vice laid off about 60 staffers in 2017 (Spangler, 2017).

The situation with licensed partner editions can be particularly challenging, as the incentives at local level may differ from those of the wider organisation. As the editor-in-chief of one partnered edition candidly put it: ‘My mission from my CEO is to grow our domestic site. [The global media organisation] has the mission to make us all work together. That’s really hard.’

Partnerships can also be complicated and partners’ motives are not always transparent. One outside observer on the situation in India notes, for example, that the Times of India, formerly HuffPost’s partner and now a partner on Vice’s expansion into the subcontinent, has previously been known to enter into partnerships with international players largely to be able to stifle their growth and thus protect its own dominant position.

There are also potential costs to the brand of going with a licensed model, as the greater scale comes at the expense of control over content. This has led some organisations to be quite selective about how their brands are licensed, and by whom. As Jay Lauf, president and publisher at Quartz, put it, ‘a brand which is distinctive and powerful here in the States and is then just sort of licensed in a Balkanised way across a variety of countries, begins to lose the essence of what the brand is.’

Editorial Strategy and Brand Identity across Countries

Defining the ‘essence of what the brand is’, as Jay Lauf puts it, is about editorial strategy and identity. Some, like Quartz and De Correspondent primarily cater to an upmarket and quite elite readership, often through a limited selection of high-quality stories on a few core topics. Others pursue a broader and more popular audience both in terms of style (more than one editor interviewed said the target tone was ‘pub conversations’) and in terms of multiple lifestyle verticals that go beyond traditional news and current affairs. Whether the target audience is upmarket or more popular, internationally oriented digital-born news media face the dual challenge of (a) carving out a clear and distinct identity in target, often very different, markets while also (b) ensuring some degree of consistency across markets. Even after several years, Jim Edwards, Business Insider UK, notes:

Part of our challenge is that technically, by numbers, we’re number one in the market [for business news]. But we’re still very much the introductory challenger brand. A lot of people still regard us as the alternative to the real business news.

The backdrop here is one that is, for good and ill, often characterised by low trust in many established media (Newman et al., 2017). This presents an opportunity for digital-born news media to stand out, and standing out is about more than content – it is also about audience engagement, covering uncovered topics, and building relations with specific communities. Brut has also launched two verticals which ‘seize’ upon the values of its readers through global topics: environment and sport. ‘Whether it’s covering the environment, minorities or discrimination – we’re paying attention,’ says Laurent Lucas, editor-in-chief. In a similar way, both HuffPost under a new editor-in-chief and De Correspondent (in collaboration with its US research partners) are teaching themselves how to work more closely with communities. The HuffPost US team has embarked on a ‘listening tour’ bus ride across the States, to source stories.

All our case organisations see themselves in some sense as niche publishers – none are seeking to be a single comprehensive source of news for all audiences – whether they define their target audience and tone on the basis of lifestyle, demographic, or politics. All also seek to cultivate and express a brand identity across channels including website, social media, and, where relevant, distinct editions. No one is interested in scale simply for the sake of scale, and each instead aims to define clear identifies and serve specific communities and specific topics (sometimes by reorienting editorial strategies that have evolved and expanded over time: HuffPost, for example, operates scores of different sections and publishes more than a thousand articles a day across its global network).

Many of our interviewees expressed their frustration at what they saw as a frequently dismissive attitude towards digital-born news media from some older journalists and legacy media in particular. Anne-Marie Tomchak, editor-in-chief Mashable UK, criticised the portrayal of digitalborn news media as content farms and click-bait factories and said:

I think there’s a misconception that new media organisations do viral news or anything that’s going to get clicked. When in fact they create stories in a really timely fashion and they also go deep.

One key challenge of developing global digital-born media is the tension between having a recognised and trusted global brand, whilst also reflecting the particular voices and interests of the individual communities being served. Internationally expanding digital-born media face the challenge of replicating their previous single-country successes in a broader set of global contexts. A clear identity and distinct niche in one market does not automatically travel across countries; HuffPost originally found a space for a liberal news and opinion site in the US, but internationally faces competition for that space in many markets for example from newspapers like the Guardian (in the UK), Le Monde (in France), and Süddeutsche Zeitung (in Germany). (Under its new editor Lydia Polgreen, the publication is instead focusing on a less ideological, more populist, approach.)

One of the strengths of having several international offices is the opportunity to work together on stories of global importance and interest. We had many examples highlighted to us of journalism produced as part of a global team, including Vice’s Refugee Week, a series on the Antarcti by HuffPost, and one on paternity leave by Business Insider. Coverage of Brexit from multiple European viewpoints was also highlighted by Vice, HuffPost, Business Insider, and Quartz.

This highlights that some kinds of news content have global reach. Indeed, the ‘Trump bump’ from the US has been a huge driver of traffic for most international media interviewed. For example, HuffPost France has leveraged its position ‘as a source of American news’, and saw a huge spike in numbers after the US president’s inauguration in January, says Paul Ackermann, editor-in-chief: ‘Trump in January was huge. In January began this huge traffic spike.’

Some issues affect people in New York or Mumbai alike, says Anne-Marie Tomchak, editor-in-chief of Mashable UK: ‘They still want to find love. They’re still using dating apps. They’ve all got the same kind of challenges.’ As such, lifestyle content also travels well. Vice highlighted evergreen and lifestyle content as readily translatable across the world, while politics is generally much more localised. Some news and current affairs stories – like the US election – have global appeal, but many found that coverage of other areas, like business, culture, and technology, travelled better than politics.

The ability to reach global audiences with the same story, though, is limited by the other key editorial theme we heard from our interviewees: the centrality of ‘local’. As Jim Edwards of Business Insider UK said, ‘It’s a lot harder for American brands to go abroad and just have success. Media is surprisingly local.’

This, then, is a major editorial advantage of local offices, and particularly of partnership approaches which use journalists already familiar with a country, its culture, and its audiences. Ciel Hunter, global head of content at Vice, simply said ‘we are local everywhere. People value where they’re from and they value what’s going on locally. So we see a lot of hyper-local coverage that also combines with global themes.’

Thus the internationalisation of digital media does not do away with the importance of the local. Business Insider France has localised ‘elements from Business Insider to very French topics’. Several media went further, and discussed reporting on particular countries from those countries in terms of ‘decolonising’:

For me, it’s really important that this is not a neocolonial exercise. We’re not interested in ‘Oh, we’re going to figure out the solution in the US and then everybody has to do that template.’ It’s very much about retaining the local flavour, from story formats to products. (Louise Roug, international director, HuffPost)

We, the Western media, tend to swoop into Africa and cover it, but as I said, we’re trying to cover the stories of technology in African solutions for African problems, if you will. (Jay Lauf, president and publisher, Quartz)

We don’t have to parachute into these places. We have people who have perspective from the places we want to write about. (John Mancini, global news editor, Quartz)

‘Local’ does not always mean ‘national’, either. Several sites put emphasis on the importance of the voices of particular groups within a given national community, such as HuffPost Germany, which featured interviews with Syrian refugees in Germany when discussing the refugee crisis.

Conversely, some media see a value in offering a global perspective to everyone. This is an approach which Quartz are taking, as Jay Lauf told us: ‘To be global, in a geopolitical moment and era where there seems to be a lot of backlash against the notion of the global economy, we’re unapologetic about it.’ This is the pull of the internationalised, global audience itself:

The typical Quartz reader would be a Vice President at a US company who is based in Brussels

but who studied in Canada and travels internationally both for work and for fun and speaks a few languages. There are a lot of those people and so I think you could call that niche in the billions of humans who exist but it’s a large group of people. (Jason Karaian, global finance and economics editor, Quartz)

Of Quartz’s global nature, Jay Lauf says: ‘in the very beginning, we sort of mandated that all our journalists speak two languages fluently so that we kind of spoke in a post-national voice. It was very deliberate.’

Quartz is an outlier in its desire to maintain a single uniform editorial voice with global aspirations. Although it has high global reach, and news teams positioned around the world, it does not offer local editions in each country, but directs most of its readership to the central Quartz output. The strongest contrast is with Vice, which has dozens of editions, most of them partnered, for countries and in languages throughout the world.

Vice highlighted the balance between their youth audience and a legacy audience that ages with the publication. They were also clear that one of the essences of their brand was that it was multilocal. Hosi Simon, global general manager:

If you’re 18 in Beijing and you come to the website, it’s about what kids in China care about: Chinese music, Chinese food, Chinese culture, Chinese issues and it feels like 100% a local Chinese media company to you. It’s made for you by people that understand you, by local Chinese.

The other digital-born media in our sample are between the two, with multi-local editorial positioning being associated with a higher number of editions and larger scale, and a single uniform voice generally with fewer editions and a somewhat smaller global reach.

The Challenges of Working Globally

Working across several countries, often on the basis of a single headquarters and multiple country editions with varying degrees of autonomy, presents digital-born news media with tensions known from other multinational organisations – between centralising and decentralising tendencies, for example, and between standardisation based on uniform standards and content tailored to reflect local needs and attitudes.

These tensions are visible in editorial priorities and brand identities, but also more basically in working processes and organisation. Where an organisational centre is responsible for maintaining a certain level of consistency and autonomous local offices are responsible for producing adapted local content, there are many possible organisational models with different kinds of output. Here, internationally oriented digital-born news media are dealing with issues that brands like the BBC and CNN face in far larger organisations with more resources, as digital-born news media have launched whole-country editions based on just a few journalists on the ground.

Such expansion increases the number of global entry points to a brand, helps leverage content produced for the home (often US) market internationally, and allows the sales and targeting of advertisements specifically to the local market. It also greatly increases the challenge of coordinating staff and content output across international boundaries. This issue is inevitably more pronounced when some of those editions are joint ventures in partnership with local news media, and the whole is not under one management, illustrating some of the possible invisible and immaterial costs of an approach that otherwise enable expansion at a lower monetary cost.

One major challenge with operating globally is the difficulty of coordinating offices across different countries, in different time zones. Jay Lauf, president and publisher, Quartz, captured the dilemma:

How do you take a team that was once 35 people in a single room or less, who are now 200 people scattered across five continents, and make sure that everybody still has the same sense of mission and purpose?

As Ciel Hunter, global head of content at Vice, said, ‘it’s a very delicate system and it requires a lot of care, a lot of communication’.

The challenges are greater if the aim is to work as a single 24-hour news team rather than as a network of local editions. One example of this is Quartz’s daily briefing newsletter. In order to circulate this to customers at the beginning of the work day, each of the three editions is put together by staff one region ‘ahead’ of the target audience: the Asia/Pacific team producing the briefing for Europe, the European staff producing the US briefing, and the US team making the Asia/Pacific briefing in time for the beginning of the next business day.

For other media organisations, this kind of handing-off of stories is a much more unusual activity, undertaken only when there are major breaking news events such as the Las Vegas shootings. In this case, there’s a need to coordinate a network of usually autonomous newsrooms to work together on a major story.

One senior international manager argued both that an international network of newsrooms was a hugely valuable resource, but also that it had been difficult to realise the value there, noting: ‘I think in the past, we were less than the sum of our parts’.

One approach taken to handling this challenge is to leverage digital technology. Slack, an instant messaging application, is heavily used by many of our sample to maintain a constantly available communications channel between offices. Where technologically supported integration is less prominent, personal relationships are one way in which different countries’ teams are kept coordinated.

More ambitiously, some digital-born news organisations are living up to their external reputations as tech companies by pioneering digital tools to inform their work – here automation is harnessed to bring down costs and empower lean editorial teams to make the most of their resources.

The ability to pursue technology as a way of supporting journalism is sometimes limited by the size of news organisations and the resources and range of skills available to them. But here it is important to note that all the internationally oriented digital-born news media we cover here invest in technology and prioritise hiring staff with an appreciation of the opportunities offered by digital-media. Technology, and technology expertise, is integral to how their newsrooms work (as also found by Küng, 2015). Marie-Catherine Beuth, editor-in-chief of Business Insider France, highlights that tech skills are an important differentiator: ‘I decided to pick people who can do a lot of things in terms of editorial content. All understand how tech works.’

Some examples include:

- Automated discovery, like Mashable’s tool ‘Velocity’, built by an in-house product team.

Anne-Marie Tomchak, editor-in-chief, Mashable UK explains that it can help inform

editorial decision-making: ‘One iteration of it is a data analytics tool where you can mine

the Internet, millions of URLs every day. You are actually news gathering, you can see

what’s picking up steam with Velocity’s predictive technology. So I can see what stories are

resonating and try to then harness that Mashable editorial around a story.’ - Automated curation, looking beyond the seven content-focused digital-born news media

we focus on here, the news aggregator and micro-payments pioneer Blendle has gone

further in the technological direction than most of the news organisations. Alexander

Klöpping, founder and CEO, explains how the company is training an artificial intelligence

system to replicate the judgement of its human editors, in an attempt to make it easier

(and cheaper) to surface interesting content at scale and in a personalised fashion. - Automated translation, for example at Vice, where the Content Management System

allows for the translation of articles via Google Translate at a click of a button, and also

tracks articles around the editions to see where an article originated and how far it travels.

(Others question how much can be achieved in this way and argue that machine translation

is not yet up to the job of producing content fit for publication. Nevertheless, some – but

not all – of the digital media companies we spoke to are interested in the prospect.)

Automated translation – here reliant on a general purpose tool provided by a large platform company – is one way of beginning to address the practical challenge of how to maximise the value of global coverage across different languages. Staff translators and the use of freelance translators is expensive, and ad-hoc translation by journalists from languages they happen to be fluent in does not work at scale. Hence automation is attractive, at least as a starting point for professionals finishing off the job.

Video, especially short-form video, was repeatedly brought up as an area where translation is relatively straightforward and the content travels well internationally. Louise Roug, international director, HuffPost:

Video, in some ways, is easier. For news it’s shorter, it has a clear script, and it has subtitles. And the visual part of it travels easily. So it’s just a matter of translating the script and putting different subtitles on it.

There is an inherent tension between the dreams of instantly available machine-translated content discussed above, and the desire for brands to have distinct voices which speak to local concerns. Many people said that some kinds of article simply didn’t make sense out of their original context, without extensive work. Louise Roug described some of this work as ‘the explanatory rewrite’, noting that the social context of, for example, the Grenfell fire in the UK, was simply not known to non-UK readers.

In general, there was a strong sense that the best way forward in most cases is adaptation rather than simple translation, with the differing local contexts meaning that simply translating a story from another edition would result in an article which was not suitable for local audiences and potentially damaged trust in the brand. We repeatedly heard that translation, although a useful tool for spreading great reporting from other editions, was not a good substitute for local news output locally written. This is particularly so for current affairs coverage, as opposed to coverage of culture, lifestyle, and technology.

From the outside, the global expansion of digital-born media can look like a straightforward replication of one market’s success into other areas, with the resulting scale offering clear financial benefits. In the organisations we’ve studied, though, we see similar challenges to those affecting any multinational business. Audiences in different markets have different preferences and backgrounds, and the content which is popular in one may need extensive adaptation to work in another. Coordinating offices in multiple time zones is an organisational challenge no less difficult for being commonplace. And tensions between centralising and de-centralising tendencies and the varying benefits and difficulties that they bring are common to all organisations. Expansion is difficult editorially and organisationally, and it can be hard to effectively monetize overseas audiences, especially if they are relatively small in each individual market.

Conclusions

Most internationally oriented digital-born news media are pursuing audience growth to generate the advertising revenues that their business model depends on. To do so, they offer free digital news via websites and apps and invest significant resources in search engine optimisation and social media promotion and publishing, and in many cases operate a number of national editions often based on a limited investment in local editorial resources, sometimes in partnerships or based on licensing agreements, sometimes run independently. All of them seek to define a niche and a brand identity, and develop editorial strategies and forms of audience engagement around these. In doing so, they deal with tensions between centralising and decentralising tendencies, and make choices about whether to pursue expansion on the basis of a relatively uniform voice (like Quartz) or a multi-local approach with numerous more autonomous local editions (like HuffPost and Vice). Most of our interviewees underline the importance of locality, of adaptation, and of tailoring content and the like to specific markets. But it is also clear that the costs and challenges involved in running a network of global newsrooms are significant and more or less straight translation is a tempting way to leverage content from other editions across markets. So far, the expansion has in many cases provided impressive top line numbers of monthly users. But in many markets, internationally oriented digital-born news media still have smaller and less engaged audiences than the most important legacy and domestic digital-born news media (Nicholls et al., 2016).

While different internationally oriented digital-born news media have different audience orientations (upmarket versus popular, heavy focus on news/current affairs versus greater emphasis on culture and lifestyle) and balance between a uniform voice or a multi-local approach to expansion, there are also clear commonalities between all the cases considered here. Most primarily base their business on advertising, most aggressively seek to leverage platform reach via search and social (and accept the platform risk that comes with this distribution strategy), and all see themselves as niche media (no one claims to be a comprehensive news source or to serve all audiences).

De Correspondent, with its emphasis on a membership model now preparing for launch in the US, and Brut, with its fully distributed approach and rapid expansion from France to first forays into India and the US, are the only two that originate outside the English-speaking world, with most internationally oriented digital-born news media coming out of the US, often with significant investment from venture capitalists, larger media conglomerates, or others interested in pursuing global expansion who have bet on the (global) expansion of these digital-born players and have been willing to fund a period of expansion based on a ‘reach first, profits later’ approach.

This approach sets most of the cases covered here apart from both the legacy media they compete with in different markets, and from the domestic digital-born news media they also face. It has worked for some – Quartz continues to grow and in 2017 reported it was profitable (Flamm, 2017). Sites like HuffPost and Business Insider have been bought for significant sums in recent years, both selling for more than the venerable Washington Post did in 2013. But it is also clear this model no more guarantees success than any other approach to digital news. The sale of Mashable in 2017 for a fifth of its 2016 valuation was described by some as a ‘fire sale’ (Sharma and Alpert, 2017). Most of our interviewees did not share details on revenues and on whether their organisation was profitable. Many digital-born news media seem to be struggling to meet their revenue projections as the digital advertising markets continue to become more challenging and competitive with the move to mobile, the rise of programmatic, competition from platform companies, and the spread of ad-blockers.

In November 2017 it was reported that several of the most ambitious and largest internationally oriented digital-born news media, including both BuzzFeed and Vice, were likely to miss their revenue projections for 2017, despite their considerable reach across website sand social media (Sharma and Alpert, 2017). Others have cut their costs in recent years, or reduced their investment in news in favour of a “pivot” to video and/or increased focus on lighter and cheaper content.

Ultimately, while their international, expansionist strategy and often the investment behind them that allows to them to pursue audience reach first, profits later, sets them apart from legacy media and from most domestic digital-born news media (especially outside the US), the fundamental challenges they face are broadly the same – how to develop editorial, distribution, and funding strategies that enable a sustainable, perhaps even profitable production of quality news in an increasingly digital, mobile, and platform-dominated media environment. Increasingly, whether domestic or international in orientation, digital-born news media aim to be editorially distinct, organisationally lean, and diverse in terms of revenue streams to ensure their long term sustainability, not unlike how many legacy media are adapting to an incredibly competitive

online environment (Bruno and Nielsen, 2012; Cornia et al., 2016). This business is challenging for internationally-oriented digital-born news media as it is for other news media. Building a sustainable business primarily around advertising risk pitting news media directly against large platform companies that offer far greater reach, much more precise targeting, and significantly lower prices. Hence the need to constantly evolve not only in terms of editorial and distribution strategy, but also business model.

Some remain bullish. Vice CEO Shane Smith has predicted a ‘blood bath’ in legacy media and see companies such as his own as the ones who are best positioned to succeed in the long run (Valinsky, 2016). Others take a bearish stance, with BuzzFeed reporter Matthew Zeitlin predicting a ‘digital media blood bath’ (Zeitlin, 2016). More broadly, the situation resembles a digital content bubble where most digital news providers continue to operate at a loss, whether sustained by profits from legacy operations or by investors betting on the long-term success of ambitious, expansionist digital born organisations. This bubble will eventually burst unless more diverse and sustainable business models are found.

Where internationally-oriented digital-born news media seem most exposed is in their reliance on one main revenue stream in digital advertising and in terms of the platform risk that comes with the dependence on especially Facebook. Where they seem strongest is when they face those challenges with a leaner organisation and a clearer strategic focus plus editorial identity than most legacy media, and make more effective use of technology, both in terms of platforms like search and social and in terms of in-house tools for automating and enabling work. In that sense, they are truly digital-born, not just on the web, but of it, not just targeting a domestic audience, but a global, world-wide one.

About the Authors

Tom Nicholls is a Research Fellow at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford. Main research interests include the dynamics of digital news and developing new methodological approaches to studying online activities using digital trace data. Most recently he has been using large-scale quantitative methods to analyse the structure, scope, and interconnectedness of government activity online, the effectiveness of electronic public service delivery, and the Internet’s implications for public management. He has published in various journals including Social Science Computer Review and the Journal of Information Policy.

Nabeelah Shabbir is a freelance journalist, formerly of the Guardian, who specialises in panEuropean journalism, global environmental coverage, and digital storytelling.

Rasmus Kleis Nielsen is Director of Research at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, Professor of Political Communication at the University of Oxford, and serves as editor-in-chief of the International Journal of Press/Politics. His work focuses on changes in the news media, on political communication, and the role of digital technologies in both. Recent books include The Changing Business of Journalism and its Implications for Democracy (2010, edited with David Levy), Ground Wars: Personalized Communication in Political Campaigns (2012), and Political Journalism in Transition: Western Europe in a Comparative Perspective (2014, edited with Raymond Kuhn).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank first and foremost our interviewees for taking the time to meet and share their insights into how their operations work as digital-born media. Their willingness to talk frankly about both challenges and opportunities for international expansion has made this report possible. Some quotes do not carry names or organisations, generally at the request of those interviewed.

We are particularly grateful for the input and support of our colleagues at the Reuters Institute for

the Study of Journalism, both for their practical support in undertaking the research and also for comments on an early draft of this report.

Published by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism with the support of Google and the Digital News Initiative.