| Statistics | |

| Population | 66m |

| Internet penetration | 84% |

Alice Antheaume

Vice Dean, Sciences Po Journalism School

2017 has been marked by an unusually intense and unpredictable French presidential election campaign, which has redefined the media landscape and where online now for the first time matches TV as a source of news.

The presidential election has been dominated by breaking news, and in particular scandals about two candidates, Marine Le Pen (extreme-right) and the previous favourite François Fillon (right), which made the campaign both more newsworthy and uncertain than previous elections. This led to a strong appetite for real-time news, which benefited the main 24-hour TV channel BFM TV, with a reach of over 45%, as well as online news sites in general. In the midst of the Fillon scandal, nine of the ten most-read articles on the Le Monde website were about the affair. Meanwhile France remains under a state of emergency since the Paris attacks of November 2015. Almost 10m people watched the debate between five major candidates, held on TF1 and LCI, five weeks before going to the polls.

The intensity of the election campaign, together with fears about extremist propaganda and the role of fake news, has fuelled several innovations. One such, CrossCheck, was launched in February with support from Google and Facebook, involving several French media companies, to fight against misinformation.1 In addition, Lemonde.fr which had pioneered French fact-checking with its team Les Decodeurs, launched a new product Les Decodex focused on fact-checking hundreds of French news websites, powered by a database of 600 of them. Le Monde has also been using Snapchat Discover to attract young audiences. Meanwhile Le Figaro planned to double its live video stream output in the run-up to the election.

In previous presidential elections new digital-born outlets were launched in France (Le Huffington Post in 2012, and Rue89 in 2007). Similarly, this year, Forbes, Business Insider, and Mashable – all American brands – launched French versions, and Politico, with two senior editors based in Paris, strengthened its presence. They are all chasing millennials and exploring new ways of monetising their brands, since digital advertising revenues are slowing down, partly due to the use of ad-blocking (31%).

In TV, in an attempt to attract young viewers, the 24-hour news channel LCI, part of the TF1 group and free to air since last year, hired 19-year-old Hugo Décrypte, a French YouTuber who creates political explainer videos. Another leading channel Itélé, owned by Vincent Bolloré, is in trouble, after a long-lasting strike in November 2016 led more than half of the newsroom to leave. It has now been renamed CNews.

In public service broadcasting, Franceinfo, which was originally a breaking-news public radio created in 1987, has been turned into a multimedia public service continuous news outlet, on radio as before, but with a new TV channel, and a new mobile application (previously called France TV Info), which is doing well online (12% of weekly reach). Franceinfo has also pioneered new formats including a new approach to fact-checking through Facebook Live videos compiled on the streets.2

Meanwhile, press circulation is still declining in France and 740 newsstands closed in 2016 (4% of the total). A new design of newsstand has been tested in the south of Paris to display a broader range of newspapers. If it helps increase the sales, it could be rolled out more widely.

20 Minutes, a free daily newspaper created in 2002, now has a wider circulation than Le Figaro, with about 937,000 copies available per day on public transport. Online, 20minutes.fr is very powerful as well, mixing soft and hard news, and with no paywall. Paying for online news is still rare, with the exception of some specialist sites like the pure player Mediapart which claims 120,000 subscribers. Le Monde is experiencing a real shift in its audience, since it now has more digital (110,000) than print subscribers (100,000).

Inspired by the special offer made to the Amazon Prime clients to read the Washington Post for free, the telecom operator SFR, whose CEO Patrick Drahi now owns the daily newspaper Libération, the news magazine L’Express, and has some shares in Nextradio TV group (BFM TV, RMC radio, and a couple of digital titles), built a mobile application named SFR Presse, to give unlimited access to all of its titles.

Changing Media

News websites in France now have more than 50% of their traffic coming from mobile. This is a result of an aggressive use of mobile notifications (20minutes.fr, lefigaro.fr, BFM online), which French mobile users seem to be especially fond of.

Trust

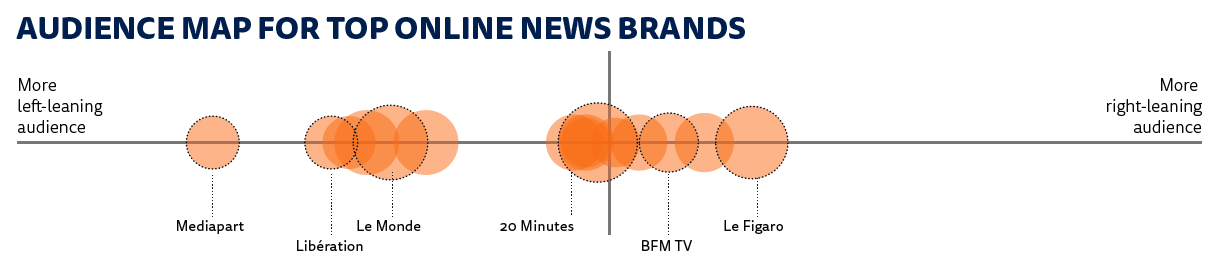

Trust in the media is amongst the lowest in Europe (30%). This may reflect concerns that editorial stories can be influenced by powerful owners with business interests to protect. It might also be connected to low trust in French politics and political institutions in general, as reflected in various surveys and the weak showing of mainstream parties in the recent elections.3