This year’s report contains signs of hope for the news industry following the green shoots that emerged 12 months ago. Change is in the air with many media companies shifting models towards higher quality content and more emphasis on reader payment. We find that the move to distributed content via social media and aggregators has been halted — or is even starting to reverse, while subscriptions are increasing in a number of countries. Meanwhile notions of trust and quality are being incorporated into the algorithms of some tech platforms — as they respond to political and consumer demands to fix the reliability of information in their systems.

And yet these changes are fragile, unevenly distributed, and come on top of many years of digital disruption, which has undermined confidence of both publishers and consumers. Our data show that consumer trust in news remains worryingly low in most countries, often linked to high levels of media polarisation, and the perception of undue political influence. Adding to the mix are high levels of concern about so-called ‘fake news’, partly stoked by politicians, who in some countries are already using this as an opportunity to clamp down on media freedom. On the business side, pain has intensified for many traditional media companies in the last year with any rise in reader revenue often offset by continuing falls in print and digital advertising. Part of the digital-born news sector is being hit by Facebook’s decision to downgrade news and the continuing hold platforms have over online advertising.

With data covering nearly 40 countries and five continents, this research is a reminder that the digital revolution is full of contradictions and exceptions. Countries started in different places, and the speed and extent of digital disruption partly depends on history, geography, politics, and regulation. These differences are captured in individual country pages that can be found towards the end of this report. They contain important industry context written by local experts — alongside key charts and data points from each market. The overall story is captured in this executive summary, followed by chapters containing additional analysis on key themes.

Summary of some of the most important findings

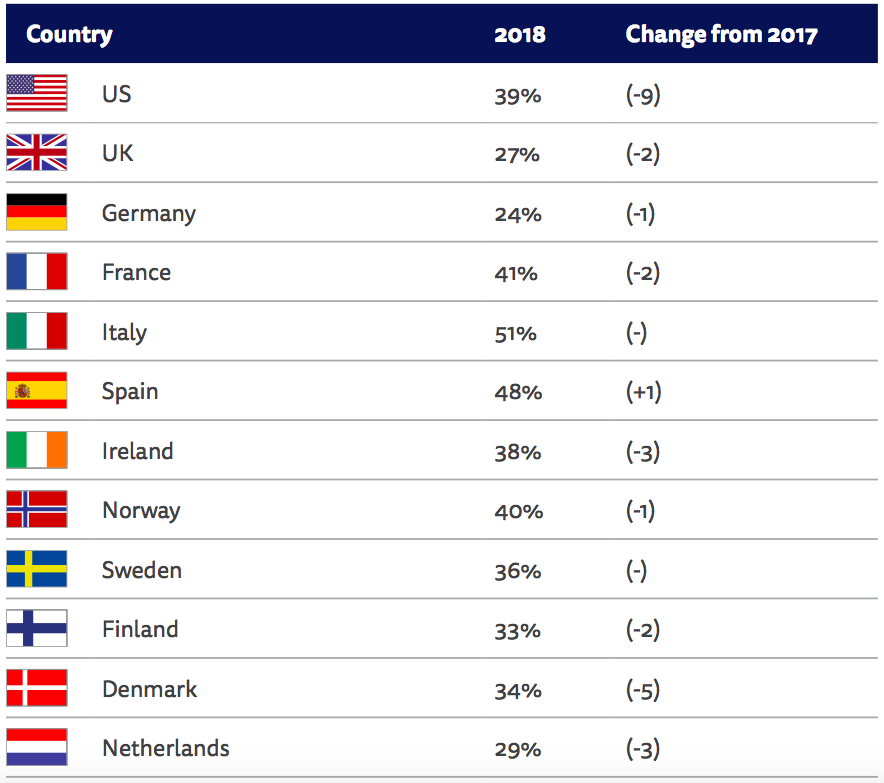

- The use of social media for news has started to fall in a number of key markets — after years of continuous growth. Usage is down six percentage points in the United States, and is also down in the UK and France.1 Almost all of this is due to a specific decline in the discovery, posting, and sharing of news in Facebook.

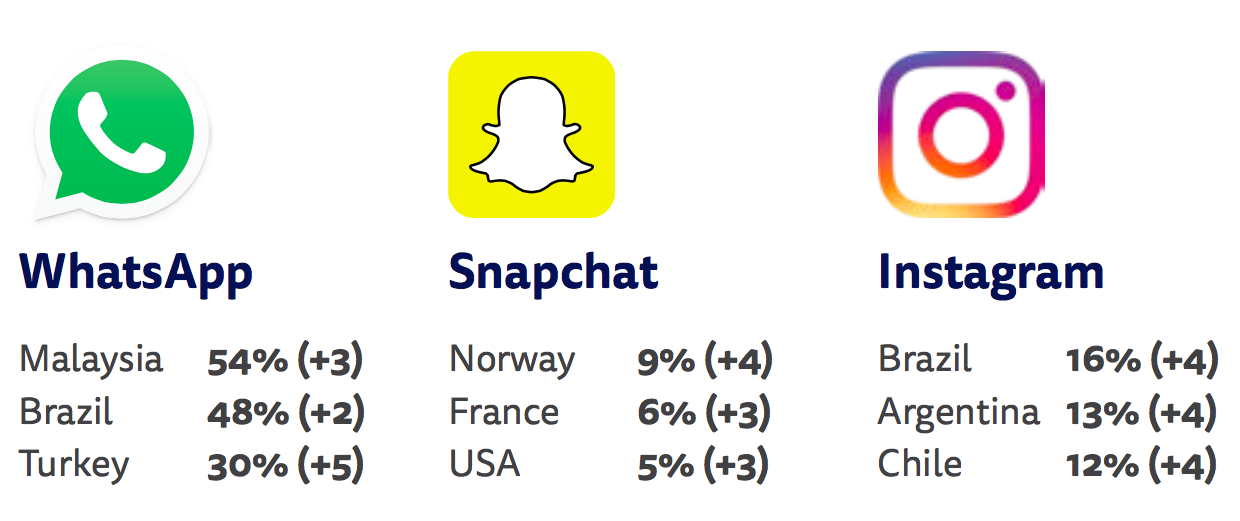

- At the same time, we continue to see a rise in the use of messaging apps for news as consumers look for more private (and less confrontational) spaces to communicate. WhatsApp is now used for news by around half of our sample of online users in Malaysia (54%) and Brazil (48%) and by around third in Spain (36%) and Turkey (30%).

- Across all countries, the average level of trust in the news in general remains relatively stable at 44%, with just over half (51%) agreeing that they trust the news media they themselves use most of the time. By contrast, 34% of respondents say they trust news they find via search and fewer than a quarter (23%) say they trust the news they find in social media.

- Over half (54%) agree or strongly agree that they are concerned about what is real and fake on the internet. This is highest in countries like Brazil (85%), Spain (69%), and the United States (64%) where polarised political situations combine with high social media use. It is lowest in Germany (37%) and the Netherlands (30%) where recent elections were largely untroubled by concerns over fake content.

- Most respondents believe that publishers (75%) and platforms (71%) have the biggest responsibility to fix problems of fake and unreliable news. This is because much of the news they complain about relates to biased or inaccurate news from the mainstream media rather than news that is completely made up or distributed by foreign powers.

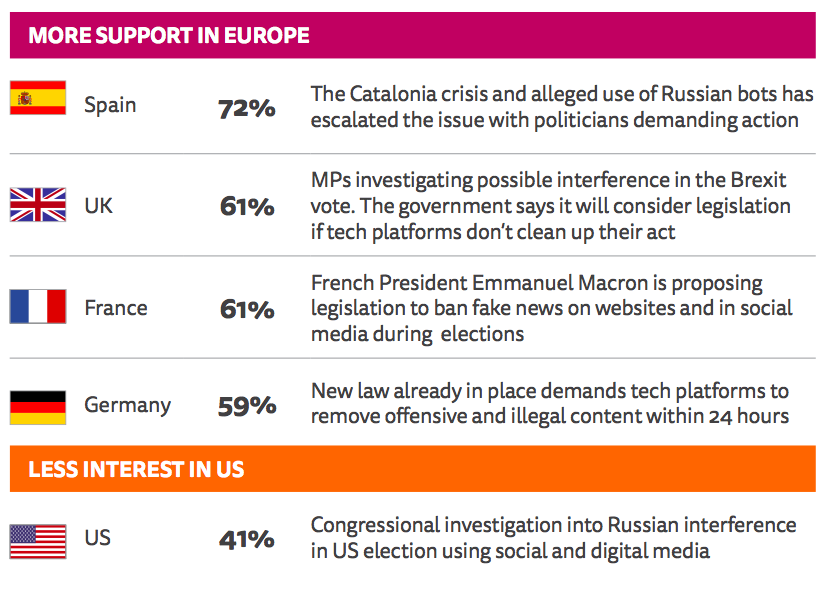

- There is some public appetite for government intervention to stop fake news, especially in Europe (60%) and Asia (63%). By contrast, only four in ten Americans (41%) thought that government should do more.

- For the first time we have measured news literacy. Those with higher levels of news literacy tend to prefer newspapers brands over TV, and use social media for news very differently from the wider population. They are also more cautious about interventions by governments to deal with misinformation.

- With Facebook looking to incorporate survey-driven brand trust scores into its algorithms, we reveal in this report the most and least trusted brands in 37 countries based on similar methodologies. We find that brands with a broadcasting background and long heritage tend to be trusted most, with popular newspapers and digital-born brands trusted least.

- News apps, email newsletters, and mobile notifications continue to gain in importance. But in some countries users are starting to complain they are being bombarded with too many messages. This appears to be partly because of the growth of alerts from aggregators such as Apple News and Upday.

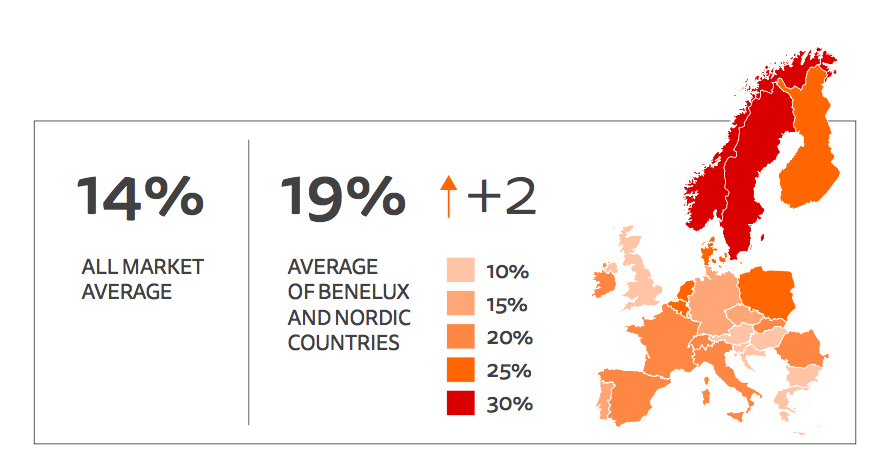

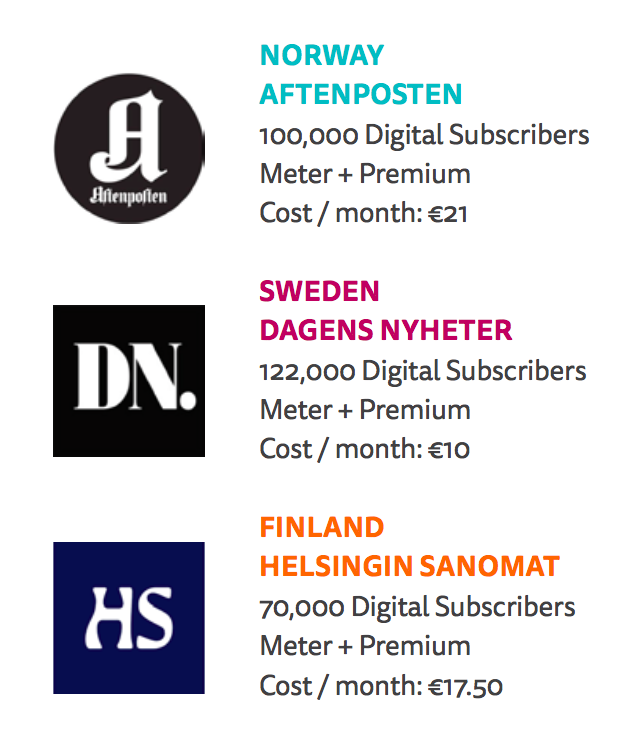

- The average number of people paying for online news has edged up in many countries, with significant increases coming from Norway (+4 percentage points), Sweden (+6), and Finland (+4). All these countries have a small number of publishers, the majority of whom are relentlessly pursuing a variety of paywall strategies. But in more complex and fragmented markets, there are still many publishers who offer online news for free.

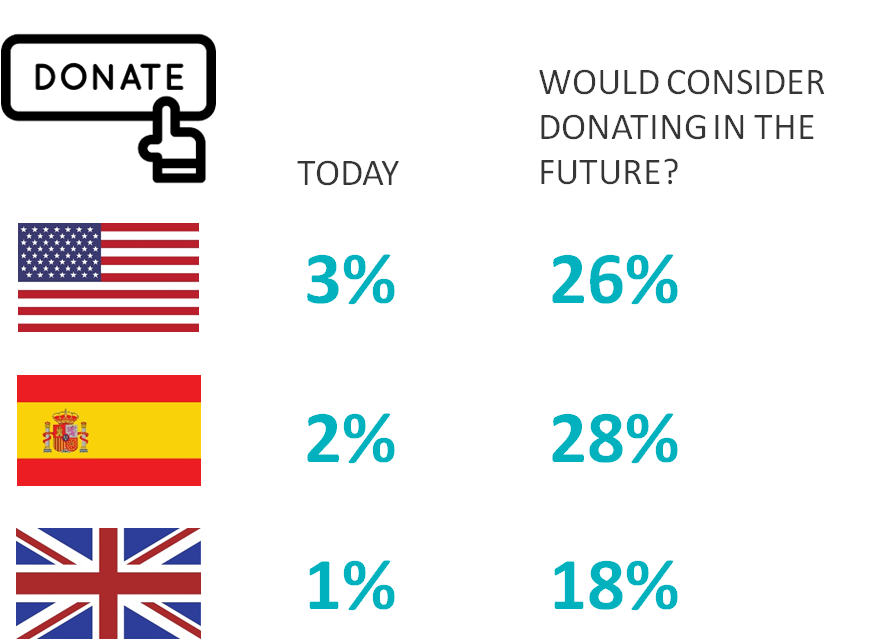

- Last year’s significant increase in subscription in the United States (the so-called Trump Bump) has been maintained, while donations and donation-based memberships are emerging as a significant alternative strategy in Spain, and the UK as well as in the United States. These payments are closely linked with political belief (the left) and come disproportionately from the young.

- Privacy concerns have reignited the growth in ad-blocking software. More than a quarter now block on any device (27%) — but that ranges from 42% in Greece to 13% in South Korea.

- Television remains a critical source of news for many — but declines in annual audience continue to raise new questions about the future role of public broadcasters and their ability to attract the next generation of viewers.

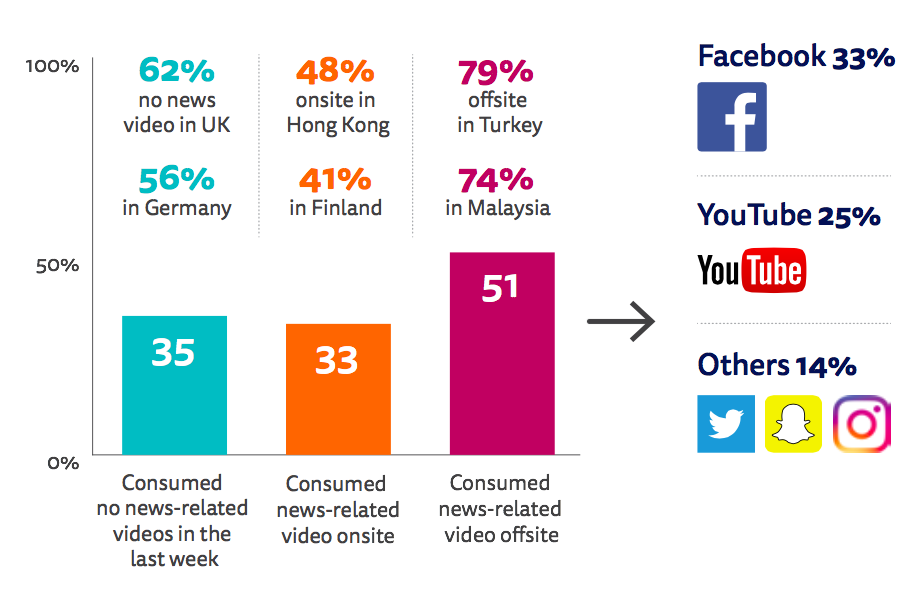

- Consumers remain reluctant to view news video within publisher websites and apps. Over half of consumption happens in third-party environments like Facebook and YouTube. Americans and Europeans would like to see fewer online news videos; Asians tend to want more.

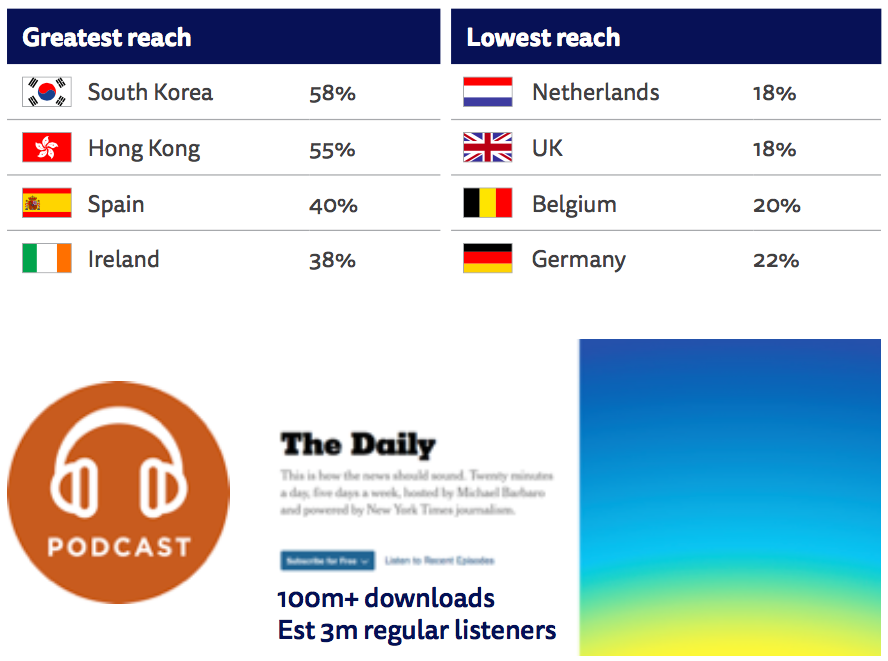

- Podcasts are becoming popular across the world due to better content and easier distribution. They are almost twice as popular in the United States (33%) as they are in the UK (18%). Young people are far more likely to use podcasts than listen to speech radio.

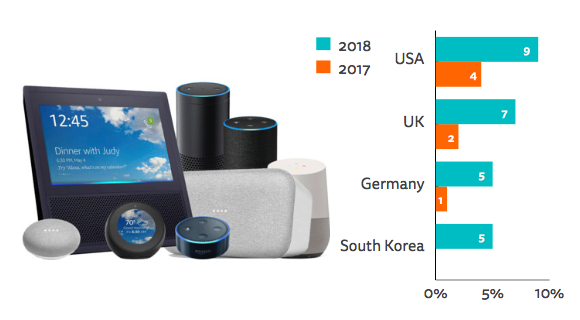

- Voice-activated digital assistants like the Amazon Echo and Google Home continue to grow rapidly, opening new opportunities for news audio. Usage has more than doubled in the United States, Germany, and the UK with around half of those who have such devices using them for news and information.

Social Media Reverse

For the last seven years we have tracked the key sources for news across major countries and have reported a picture of relentless growth in the use of social media for news. Now, in many countries, growth has stopped or gone into reverse.

Taking the United States as an example, weekly social media use for news grew steadily from 27% in 2013 to a peak of 51% before falling back significantly this year to 45% (-6). To some extent this represents a readjustment after the social media frenzy around the Trump inauguration last year — but these patterns also exist elsewhere. In the UK usage grew from 20% in 2013 to 41% in 2017 before falling back. The decline in Brazil appears to have started in 2016.

Looking in more detail at these declines, we can see that they are almost entirely due to changes in the use of Facebook, consistently the most widely used social network for news in almost every country. News consumption via Facebook is down 9 percentage points in the United States and 20 points with younger groups. In our urban Brazilian sample the use of Facebook for news has fallen to 52% — a 17 point change from 2016. It is important to note that the decline is not universal. Facebook news usage is up significantly in Malaysia and the Czech Republic. But in most countries the picture is one of decline.

PROPORTION THAT USED FACEBOOK AS A SOURCE OF NEWS IN LAST WEEK – SELECTED MARKETS

Q12b. Which, if any, of the following have you used for finding, reading, watching, sharing or discussing news in the last week?

Base: Total 2017/2018 sample in each market

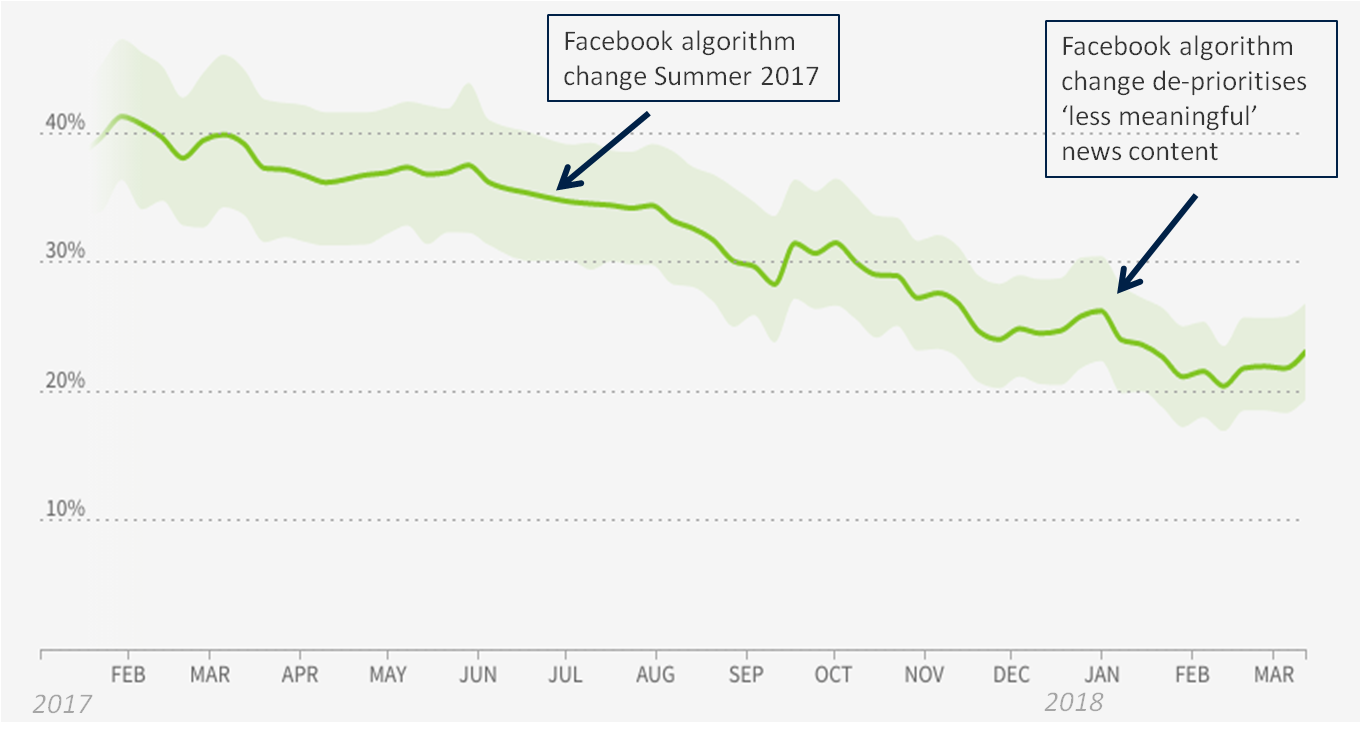

It is worth noting that average Facebook use for any purpose has remained broadly static since 2015, while its use for news has declined. This suggests either a fall in general engagement or a reduction in exposure to news by the Facebook algorithm, as the company prioritises interactions with family and friends and tries to limit the impact of ‘fake’ news. At the same time we have seen a rise in the usage of alternative platforms such as WhatsApp, Instagram, and Snapchat. In the next two charts we have averaged social news usage for around a dozen of the countries we have been tracking since 2014. Average news usage for Facebook has fallen from 42% in 2016 to 36% today while other networks are stable or have been growing rapidly.

It should be noted that our polling was conducted (mostly) before the implementation of a much-publicised Facebook algorithm change in January 2018 reorientating towards ‘meaningful interactions’, with a consequent reduction in news content. Since then, a number of publishers have reported a further substantial decline in referrals. One publisher, Little Things, went out of business in early 2018, citing Facebook’s algorithm changes as a critical factor.2

PROPORTION OF REFERRALS TO NEWS WEBSITES FROM FACEBOOK (FEB 2017–MAR 2018)

Source: Parsely

Based on share of referrers attributed to Facebook across 2500 publishers across countries within the Parsely network

Other Networks are Taking up the Slack

WhatsApp use for news has almost tripled since 2014 and has overtaken Twitter in importance in many countries. But this conceals wide variations from 54% in Malaysia (+3) and 48% in Brazil (+2) to 14% in Germany (+2) and just 4% in the United States (+1).

There have also been substantial increases in the use of other networks in a number of countries. WhatsApp and Instagram have taken off in Latin America and parts of Asia. Snapchat is making progress in parts of Europe and the United States, particularly with younger users.

PROPORTION THAT USED EACH SOCIAL NETWORK FOR NEWS IN THE LAST WEEK – SELECTED MARKETS

Q12b. Which, if any, of the following have you used for finding, reading, watching, sharing or discussing news in the last week?

Base: Total 2017/2018 sample in each market

To some extent these increases have also been driven by publishers changing their strategies, in a bid to become less dependent on Facebook. For example, more media companies have adopted the ‘Instagram story’ format, which now attracts around 300m daily active users per day.3 The BBC have extended their activities on Instagram into longer features and quizzes reaching 4.8m followers.

Meanwhile, Snapchat became an important source of news during the school shootings in Florida in February 2018, illustrating the subsequent anti-gun protests across the state with a navigable map (see below). The Snapchat Discover (news section) now reaches 17% of 18–24s in the United States, 13% in France, and 32% in Norway.

What I’ve noticed was Facebook was everything to me but now Snapchat and Instagram through different mediums are coming right up and making things more convenient than Facebook.

(M, 20–29, US focus group)

SNAP MAP OF STUDENT PROTESTS ON GUN LAWS

Source: Snap Inc.

BBC REFOCUS ON INSTAGRAM

Source: BBC/Instagram

WhatsApp does not currently make it easy to distribute news or engage directly with users, but a number of media organisations in Latin America and Spain have been experimenting with ‘broadcast lists’, news groups, quizzes, and audio notes.

Why are Consumers Relying Less on Facebook for News?

Survey and focus group evidence suggests a combination of push and pull factors at play. Consumers are being put off by toxic debates and unreliable news, but they are also finding that alternative networks offer more convenience, greater privacy, and less opportunity to be misunderstood.

“Multi-faceted, creepy, ego-centric, uncool uncle, mid-life crisis, clean, generic”

“Best friend, fun, brings people together, straightforward, honest, reliable, discrete”

Source: Focus group participants aged 20-45 in US, UK, Brazil, Germany. Conducted Feb 2018.

One common theory is that people’s Facebook networks have got so big over time that they no longer feel comfortable sharing content openly. As a result, they are moving discussion to messaging apps where they can be sure that they are talking to ‘real friends’. This is sometimes referred to as context collapse,4 an idea reflected in these focus group comments.

I use Facebook less, because I don’t want to have a close contact to many of my ‘friends’ there. These friends on Facebook are not important for me anymore. With my inner circle of friends I communicate via WhatsApp.

(M, 20–29, Germany)

It’s a message to you [on WhatsApp] not a message to everyone.

(F, 30–45, US)

Focus group respondents still talk about finding stories on Facebook (and Twitter) but then they will often post them to a WhatsApp group for discussion, often using a screen grab or a headline without a link. This is partly to avoid uncomfortable political debates over Brexit or Donald Trump:

I’ve actually pulled back from using Facebook a lot since the whole political landscape changed over the last few years because I just find everyone’s got an opinion.

(F, 30–45, UK)

Even though you may disagree with your friend on WhatsApp, friends are able to keep that good level of respect, everybody shares their opinion, and anyone who disagrees can joke about it. It’s a lighter mood to debate news with friends on WhatsApp than on Facebook.

(M, 20–29, Brazil)

Mark Zuckerberg has pledged to fix Facebook and to recreate a safer and less toxic environment. Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey has also made cleaning his network of trolls and harassment a priority. The next year is likely to be a critical test for both companies in restoring trust and interaction on their platforms. Facebook believe that deprioritising some news content is part of that process, but our qualitative research suggests they need to be careful. Consumers still value news as part of the wider mix — they would just like it to be more reliable and more relevant. With discussion moving to other platforms, they say, Facebook could end up feeling rather empty.

Messaging Apps on the Rise in Authoritarian Countries

A safe place for free expression has been one factor driving the rapid growth of messaging apps in markets like Turkey, Malaysia, and Hong Kong. In our data we find a strong correlation between use of networks like WhatsApp and self-expressed concern about the safety of posting political messages. The highest levels of concern (65%) are in Turkey where a failed coup two years ago led to opponents of President Erdoğan being jailed and the media muzzled. In a country that the US NGO Freedom House recently labelled ‘not free’ for the first time, encrypted messaging apps like WhatsApp have proved a relatively safe way to express political views. Malaysia which is labelled ‘partly free’ by Freedom House is introducing news laws that could see anyone convicted of peddling fake news imprisoned for up to six years.5

Gateways to News

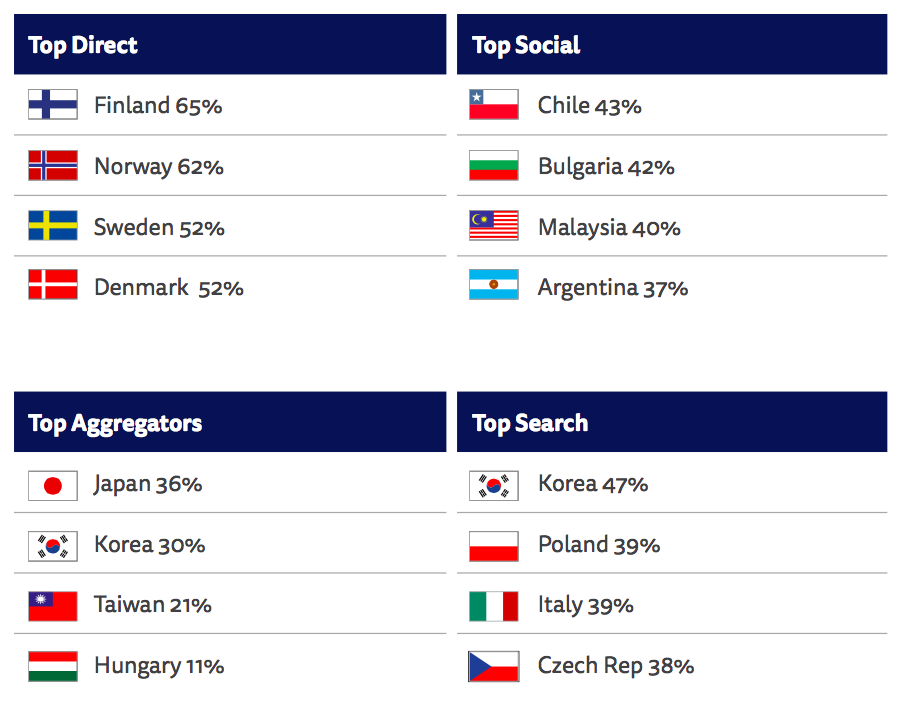

The vast majority of our respondents (65%) prefer to get to news through a side door, rather than going directly to a news website or app. Over half (53%) prefer to access news through search engines, social media, or news aggregators, interfaces that use ranking algorithms to select stories, rather than interfaces driven by humans (homepage, email and mobile notifications).

Our survey has tracked the advance of distributed and algorithmic access over the last seven years but this year’s data suggest a pause at least. The figures are almost identical with a year ago — with just mobile alerts, which tend to be produced by human editors, edging up slightly.

Behind the averages, however, we find very significant country differences. Two-thirds of respondents in Finland (65%) and Norway (62%) prefer to go direct to a website or app. Elsewhere, preferred access is often via social media, with over four in ten preferring this route in Chile (43%), Bulgaria (42%), and Malaysia (40%). In some Asian countries, aggregators or search are the main gateways. In South Korea, where Naver and Daum are dominant platform players, 47% say they prefer to access via search and 30% via a news aggregator. Just 5% prefer to go directly to a news website or app, by far the lowest in our survey. In Japan, where Yahoo! is the main news portal, the figure is just 15%.

PROPORTION THAT SAY EACH IS THEIR MAIN GATEWAY TO NEWS (SELECTED MARKETS)

Q10a_new2017_rc. Which of these was the MAIN way in which you came across news in the last week? Base: All that used a gateway to news in the last week in each market. Note: Base size is around 2000 in each market.

These differences in preferred access points are critical. They show that Nordic publishers still have direct relationships with their readers, making it much easier to charge for content online. Korean and Japanese publishers, on the other hand, find themselves much more dependent on third-party platforms to access audiences.

Age Differences

Though the shift to distributed and side door access seems to have slowed down for now, this may just be a temporary pause with new technologies such as Voice on the way. The demographic push from under 35s remains towards greater use of mobile aggregators and social platforms and less direct access. Pulling in the opposite direction is the rebirth of email, which is being used as an effective tactic to bring consumers back to news websites directly, but this channel mainly resonates with over 45s. It is unlikely to attract younger users.

Notifications as a Gateway

The fastest growing gateway to news over the last three years has been mobile news alerts. These resonate with younger users who frequently start their day with the lock screen. Picking up on this opportunity, publishers have been sending more alerts on a wider range of subjects. They are also starting to use artificial intelligence (AI) to make them more relevant. In the last year we have seen strong growth in Latin America, Spain, and most of Asia. Access has been stable in the US, UK, and much of Europe after two strong years of growth.

One key question for news companies is whether consumers are receiving too many alerts from too many different providers. Our data show that for those receiving alerts the average number of organisations sending alerts is highest in Hong Kong (5.6) and lowest in the UK (3.1), with an average of 4.2 across all markets.

One reason for these relatively high numbers is that aggregators like Apple News and Upday are now sending alerts automatically in addition to individual news providers. This has increased the number of alerts but also the number of duplicate alerts – and also led to some confusion about where alerts may come from.

I don’t know the name of the app. I have an app on my phone, it was already there from the beginning, and breaking news notifications pop up there just like when I get a message.

(F, 20–29, Germany)

Across all markets twice as many people say they get too many news alerts (21%) as too few (10%), though the majority (65%) still feel they are getting the right amount.

Only in the UK do more people say they would like to get more alerts than fewer. This is likely to be partly because the BBC News app, which sends alerts to around 5m people, is relatively restrained.

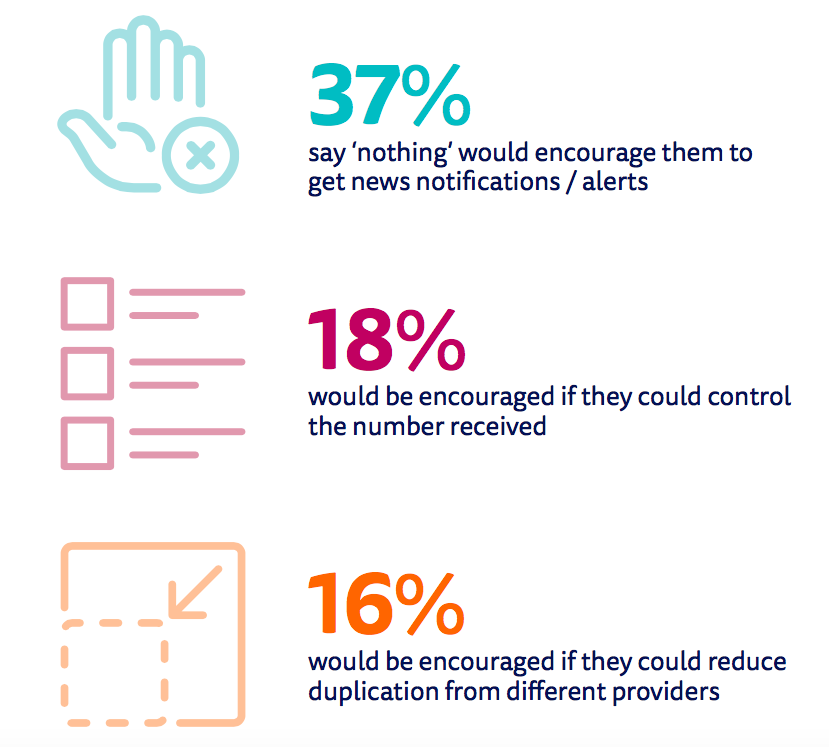

Attracting More People to Use Alerts

Around four in ten of those not using alerts (37%) say that nothing would persuade them to sign up. But there are opportunities amongst other smartphone users who are interested in news but so far have been reluctant to sign up. The main barriers are the fear of being bombarded with notifications (18%), and concern about receiving the same alert multiple times (16%).

PROPORTION THAT SAY EACH REASON WOULD ENCOURAGE THEM TO USE NEWS ALERTS

Selected markets

Q10b_2018_4. You use a mobile device but said you have not received a mobile notification in the last week, which of the following features would encourage you to use or install alerts/notifications for news?

Base: All that use a smartphone or tablet but did not receive a news alert in the last week: Selected markets = 44746.

Trust in the News Media

Winning consumer trust is becoming the central issue of our times as businesses compete for attention in a digital world — and where user allegiance can transfer in the blink of an eye. As the Edelman Trust Barometer6 has documented, trust has been declining in many institutions, as well as in the news media, over many years.

But have we now reached the bottom? At an aggregate level, this year, we see a relatively stable picture. Fewer than half of us (44%) say we trust the media most of the time but we are more likely to trust media we use ourselves (51%). This has increased by 2 percentage points in the last year.

PROPORTION THAT SAY THEY TRUST NEWS FROM EACH SOURCE

Q6_2018_1/2/3/4. Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements. I think you can trust ‘most news’/’news I consume’/’news in social media’/’news in search engines’ most of the time.

Base: Total sample in all markets = 74194.

By contrast, only a third of our aggregated sample says they trust the news they find in search engines (34%) most of the time, while news in social media is seen as even more unreliable (23%). This reflects the previous discussion about the often unsatisfying experience of news in Facebook, but is also a natural consequence of seeing more sources when in aggregated environments (Digital News Report, 2016, 2017). If these perspectives are different — which they often are — this can lead to confusion, greater scepticism, and ultimately to a lack of trust.

Looking at more detailed data on general news trust, we see more movement and significant variations across countries. Finland is holding steady at the top (62%) along with Portugal (62%). Greece (26%) and South Korea (25%) remain anchored at the bottom, though their scores have each increased by 2 percentage points. Trust in the news is substantially up in a number of countries, notably Ireland, Canada, the Netherlands, and Slovakia.

Declining trust often seems to be linked to political tension. Trust is down 7 points in Spain (44%) as the media have become caught up in the wider splits in Spanish society after the Catalan referendum. It is also down in Austria (-4) following a divisive series of elections and in Poland (-5) where the government has been accused of cracking down on private media in the name of combating ‘fake news’.7

Polarisation and Trust in the United States

The impact of Donald Trump’s first year as US President can be seen in the next chart, which also shows how polarised the news media have become. Trust was already unevenly distributed in 2016, but post-election we find that those who identify on the left (49%) have almost three times as much trust in the news as those on the right (17%). The left gave their support to newspapers like the Washington Post and New York Times while the right’s alienation from mainstream media has become ever more entrenched.

This chart reminds us that trust or (lack of trust) in the media is closely linked to perceived political bias. In this year’s Reuters Institute Memorial Lecture, Washington Post Editor Marty Baron accepted that in the United States ‘tribalism in media consumption is becoming more pronounced’,8 which is why attempts to improve trust levels with better facts or more transparency alone may not be enough. Inclusive reporting that bridges political divides and reflects different perspectives and voices will need to be part of the solution too.

Brand Level Trust

We can see this story about polarisation and perceived bias expressed in a new and powerful way with the help of brand level trust scores. For the first time this year, we asked respondents to score top brands in each country (where 0 is not at all trustworthy and 10 is completely trustworthy). Taking the US as an example, we can see scores for all those who have heard of the brand, followed by a second score for those who have actually used it in the last week. Local television news is most trusted, with a mean score of over six (6.5), and Breitbart least trusted (3.69). However for those who use Breitbart regularly, the trust score jumps to 6.96 reflecting its highly partisan user base.

We can also look at the same data through a political lens. In the next chart the trust scores of those who self-identify on the right are represented by blue dots, those from the left by pink/purple dots, and those in the centre with yellow dots.

Fox News and Breitbart have much higher levels of trust from those on the right (represented by the blue dots) whereas CNN and MSNBC show the reverse. Those on the left give CNN a score of 7.1, with right-leaning respondents rating the network just 2.4. Fox News gets a high rating from the right (6.9) and a very low one from those on the left (2.4). Breitbart News is also well trusted on the right (5.5) but those on the left give it a score of less than two (1.9). Similar charts for other countries (e.g. Germany and UK) show far narrower gaps in partisan trust.

Trust Scores and Facebook

These scores are important because Facebook have decided to ask an almost identical question of their community as part of the response to what they call ‘false news’. It’s not entirely clear how they will use the results in their ranking algorithm but it is likely they will downgrade brands with low trust scores and upgrade brands with high scores. This process has already started in the US where they have also said they will uprate brands that are trusted by different types of people.9

Facebook will not reveal their scores, but we are publishing our results for the top news brands in our 37 country pages. If Facebook mainly look at all those who have heard of the brand, this is likely to benefit established brands like the New York Times in the US or BBC News in the UK. This approach would also tend to down-rate hyper partisan brands like Breitbart because they do not have trust with different types of people. On the other hand, if they take notice of whether an individual uses the brand, people could see more content from hyper partisan sites.

Looking at brand trust across countries, we find that TV brands (or digital brands with a TV heritage) score best, followed by upmarket newspaper brands. Digital-born brands and popular newspaper brands do worst. Public broadcasters (PSBs) score best in countries where they are seen to be independent of government. But in countries like Italy and Spain they have lower scores in absolute terms but also in relation to other types. In Spain, flourishing digital-born brands carry more trust than any type of ‘legacy media’.

Fake News Explored

Related to trust, we have asked a series of further questions this year to understand public concern about ‘fake’ or unreliable news. This is a difficult area to research because the term is both poorly defined and highly politicised. Our approach was, first, to ask about general concern to capture variation across countries and then to break the term down to understand how much people were exposed to different types of unreliable information, identified by audiences in focus groups last year.10

More than half of our global sample (54%) expresses concern or strong concern about ‘what is real or fake’, when thinking about online news. There are significant country variations, with Brazil (85%), Spain (69%), France (62%), and the US (64%) at the top end. These are all polarised countries where recent or ongoing election or referendum campaigns have been affected by disinformation and misinformation. By contrast, there is much less concern in Germany (37%)11 and the Netherlands (30%)12 where recent elections passed off largely without alarm. It is also worth noting that politics tends to be less polarised in these countries and social media play a less important role as a source of news.

Defining Fake News in More Detail

In focus groups (UK, US, Brazil, Germany this year) we find that ordinary people spontaneously raise the issue of ‘fake news’ in a way they didn’t a year ago. This is not surprising given extensive use by some politicians to describe media they don’t like — and widespread coverage by the media. But we find audience perceptions of these issues are very different from those of politicians and media insiders.

Yes, people worry about fabricated or ‘made up’ news (58%), but they struggle to find examples of when they’ve actually seen this (26%). Of all our categories this is the biggest single gap between perception and what people actually see. Even in the United States, examples tend to be historic rather than current:

I think during the election, the biggest thing I disliked about Facebook was the amount of fake stories that were on there. And I think since then it has gotten so much better.

(M, 30–45, US)

Looking at our survey results, we find that when consumers talk about ‘fake news’ they are often just as concerned about poor journalism, clickbait, or biased/spun journalism. Indeed, this is the type of misrepresentation that they say they are most often exposed to (42%).

I see fake news every day. I mean for example, some of the stuff is just mediocre and over exaggerating and it’s not always what it seems.

(F, 30–45, US)

While politicians and the media often talk about fake news in terms of Russian propaganda or for-profit fabrication by Macedonian teenagers, it is clear that audience concerns are very different, relating to different kinds of deception largely perpetrated by journalists, politicians, and advertisers.

Mixed Picture for Government Regulation of Content

Across countries respondents think that media companies and journalists have the biggest responsibility (75%) to sort this out, not surprising given that most of the content they describe as fake news is generated by them. Consumers also think that tech companies like Google and Facebook should do more to prevent misinformation (71%). But there is a much more mixed picture when it comes to government intervention.

While almost two-thirds (61%) agree that governments should do more, it is striking that sentiment is much more in favour of action in Europe (60%) than in the United States (41%), where the issue of ‘fake news’ seems to have had the most impact.

PROPORTION THAT AGREE THE GOVERNMENT SHOULD DO MORE TO COMBAT MISINFORMATION

Q_MISINFORMATION_4_2_3. Please indicate your agreement with the following statement. The Government should do more to make it easier to separate what is real and fake on the internet.

Base: Total sample in each market.

In the United States, focus group participants were extremely wary of government interference, preferring to solutions that encouraged users of the platforms to behave more responsibly.

Well it’s free speech, right.

Yeah it’s what our country is based on, right?

You can’t have the government doing that.

(Fs, 20–29, US)

But in Germany, there was a different picture with respondents often recognising the value of government intervention.

I noticed that disclaimed content is removed within a few hours.

If the trolls stop posting inadequate comments and debates that would be great.

(M, 20–29, Germany)

This research is a timely reminder that there is no clear agreement on where the limits of free speech should be set. In the design of their software, US technology companies have long reflected a perspective that is heavily influenced by the First Amendment, but that is now running up against European and Asian traditions that are more mindful of the historic dangers of unregulated free speech. Striking the right balance, particularly at a time of greater polarisation, will be critical for society but also for journalism.

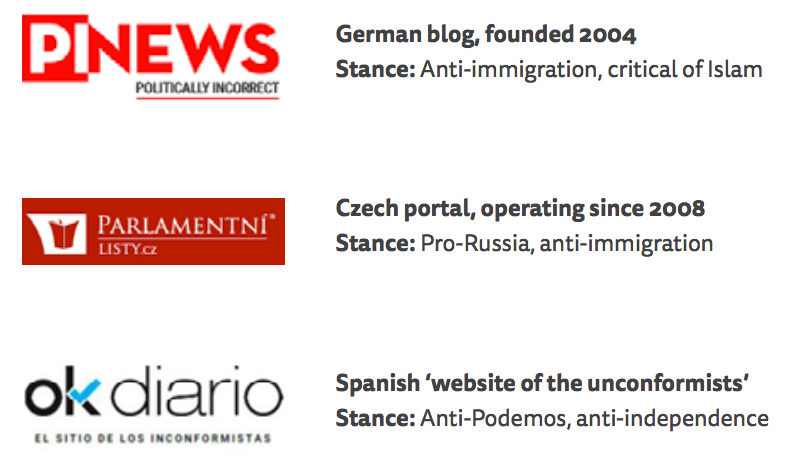

The Rise of Alternative and Partisan News Websites

In recent years we’ve seen the emergence of a number of alternative, populist, or partisan websites that have grown rapidly in some countries largely through free social media distribution. In most cases these sites have a political or ideological agenda and their user base tends to passionately share these views.13 Examples are Breitbart and InfoWars in the United States (right-wing), the Canary and Evolve Politics in the UK (left-wing).

These sites should be distinguished from those that ‘deliberately fabricate the news’, even if they are often accused of exaggerating or tailoring the facts to fit their cause. Partisan sites are said to have played a part in bringing Donald Trump to power in the United States and in mobilising support for Jeremy Corbyn in the UK. Though ideology is a key motivator, some sites are also looking to make money from these activities. The narrowness of their focus also separates them from established news sites like Fox News and Mail Online, which also have a reputation for partisan political coverage, but tend to cover the full range of news (world news, sport, entertainment). Their audiences also tend to be more mixed in terms of left and right.

This year we wanted to understand if these newer, alternative sites and blogs were gaining traction outside the United States. We worked with local European partners in ten countries to identify a number of sites that matched our criteria; namely websites or blogs which have a political or ideological agenda, mainly distributed through social media.

This methodology has a number of drawbacks; these sites are hard to classify and compare. We may have failed to capture important sites in some countries and survey respondents may not always remember smaller sites that they come across in social media.

Firstly, we compare the United States with the United Kingdom and Germany, both of which have significantly lower levels of usage. Breitbart, for example, reaches 7% of the US sample each week, 2% in the UK and just 1% in Germany where it cancelled plans to operate a local website in 2017. 14. In all three countries we also see a large gap between awareness of these sites and actual usage. This suggests either that their impact has been amplified by mainstream media coverage or that people have used them in the past, but that they are less relevant today.

Most partisan sites in the United States come from a right-wing perspective and are popular with users who see the mainstream media as overwhelmingly liberal. Many are run by talk radio hosts (InfoWars, TheBlaze), or outspoken conservative commentators (Daily Caller). Here, one survey respondent offers a clear rationale for using these sites.

Quite frankly, I get more substantial “real” information from The Blaze and Infowars than I get from today’s fake news media and government pundits.

(M, 76, US)

In the UK there is more of a political mix. Westmonster (2%) is a pro-Brexit site partly funded by right-wing businessman Arron Banks, while the Canary (2%), Another Angry Voice (2%), and Evolve Politics (1%), represent various shades of radical opinion on the left. Wings over Scotland is a popular and influential blog that fights for Scottish independence. Users of these sites say they are looking for alternatives to the mainstream media:

I’m keen for Brexit to happen. Westmonster and similar news providers report on news the BBC and others avoid because it does not fit with their biased view.

(M, 66, UK)

MSM [mainstream media] is biased, always covers the news to show the Tories in a good light, you have to look further if you want the truth

(F, 48, UK)

In Germany it might be more accurate to characterise these sites as anti-establishment. Politically Incorrect News (2%) takes a critical stance on Islam15 along with multiculturalism and immigration and attracts an audience from the extreme left as well as the extreme right. Compact Online (2%) is closely associated with the right-wing populist party AfD16, while Junge Freiheit (3%) is a nationalist newspaper brand that is reaching new audiences on the web.

Next we compare three more countries with active alternative and partisan sites. In the Czech Republic a number of sites have labelled as disinformation websites by NGOs as well as the Centre against Terrorism and Hybrid Threats set up by the Ministry of Interior in 2016. The best known alternative site is Parlamentnilisty.cz which reaches 17% of our sample17. Other websites, many of which pursue an anti-EU and pro-Russian agenda, have a more limited reach.

In Sweden, a small number of right-wing websites reach around 10% of our sample each week with an agenda that is largely critical of the country’s liberal immigration policy. Meanwhile in Spain the situation is a little different. The weakness of mainstream media has spawned a large range of alternative political websites and blogs, some of which have existed for many years. Libertad Digital and Periodista Digital follow an anti-Podemos and anti-Catalan independence agenda. Other sites such as Dolça Catalunya (3%) and Directe.cat (3%) focus exclusively on the Catalan issue but from opposing perspectives. OK Diario, which styles itself as the ‘website of the unconformists’, has featured in our list of main Spanish online sites for the last few years with 12% weekly reach.

PARTISAN AND ALTERNATIVE WEBSITES IN EUROPE

They tell the truth I like, not the damned politically correct truth.

(M, 65, Spain)

These sites reflect the wider populist and anti-establishment movements that are sweeping Europe. Many set out to present an alternative to mainstream media, which they see as part of a corporatist or politically correct consensus. For the most part, their reach remains limited, but high awareness suggests that their perspectives have been noted by the public and by mainstream media.

These sites have been able to gain currency through social media distribution. But as Facebook takes into account trust scores, becomes more risk averse on content, and refocuses on friends and family, we could see these alternative websites struggle to retain attention.

Paying for Online News

While digital advertising remains a critical source of revenue, most publishers recognise that this will not be enough, on its own, to support high quality journalism. Across the industry we are seeing a renewed push to persuade consumers to pay directly for online news through subscription, membership, donations or per-article payments.

Our data suggest that these efforts are paying off in some countries, but not yet in others — with significant progress being made by Nordic countries in particular. Substantial increases have come from market leaders Norway (+4) and Sweden (+6), as well as Finland (+4).

All these countries have a small number of publishers who are relentlessly pursuing a variety of paywall strategies. They have the added benefit of coming from wealthy societies that value news, have a strong subscription tradition, and where language and the small size of their market protects them from foreign competition.

Many Norwegian newspapers use a hybrid paywall model (a combination of a monthly page view limit and some premium content) supported by data driven editorial and marketing teams looking to convert users. Using these techniques, AftenPostenreached 100,000 digital subscribers in December 2017 after just two years.

Norwegian publishers are even able to charge for local news. The Amedia group, which runs about 60 local newspapers and websites, has 160,000 digital subscribers, up 45% on last year. Adjusting for population size, this would be the equivalent of Trinity Mirror in the UK selling 2m digital subscriptions — or 10m for Gannett in the United States.

In Sweden, leading daily Dagens Nyheter (DN) has more than 120,000 digital subscribers, with an average age 20 years younger than the print readership. The company uses predictive data techniques to target likely new subscribers and reduce churn.

In Finland quality news provider Helsingin Sanomat has returned to growth after 25 years of declining circulation — thanks to digital. They have 230,000 readers who pay for digital access, of whom 70,000 are digital only (up 40% in the last year) — part of a total subscriber base of almost 400,000.

It is not clear if the conditions for this Nordic success are replicable elsewhere but more publishers across the world are now experimenting with these approaches.

Trump Bump Maintained

In the United States, last year’s Trump Bump in subscriptions has been maintained with a headline rate of 16% paying for some kind of online news. Elsewhere, there has been a slight uptick but progress remains painfully slow.

The main beneficiaries of the US surge in subscriptions since 2016 have been liberal newspapers like the New York Times and the Washington Post. The Times has increased digital subscription revenues by almost 50% in the last year as it heads for a target of 10m subscribers globally. The Washington Post does not give official numbers but an internal memo revealed digital-only subscribers had reached more than 1 million, doubling in the last year.18 As the following chart shows, almost all the growth in the last two years has come from those who identify on the left or in the centre — along with under 35s. This is clear statement from those groups about the continuing need for high-quality journalism that can hold the Trump administration to account. These are also frequently respondents with much higher trust in news than most Americans.

Across countries, future likelihood to pay has also increased amongst those who are not already paying. Almost one in five (17%) of those who were not already paying said they are likely to do so in the next twelve months — up 2 percentage points on a year ago.

Rise in Donations from a Low Base

The rise of subscription has raised concerns about a two-tier system, where high-quality news is reserved for those who can afford it. This is why some news organisations prefer to keep access free but to ask for voluntary contributions.

In the UK, the Guardian adopted the approach in 2016 and since then it has received 600,000 voluntary payments, raising tens of millions of pounds each year.19 It has also started to crowdfund around specific stories such as the recent US school shootings where it raised $125,000 to produce solutions-based reporting.

In the UK, the Guardian adopted the approach in 2016 and since then it has received 600,000 voluntary payments, raising tens of millions of pounds each year.19 It has also started to crowdfund around specific stories such as the recent US school shootings where it raised $125,000 to produce solutions-based reporting.

Digital-born organisations in Spain have been partly funded this way for some time, along with National Public Radio (NPR) in the United States and some local news non-profits. Some partisan and right-wing websites also appeal regularly for donations.

We find that relatively small numbers currently donate to news organisations — just 1% in the UK and Germany, rising to 2% in Spain and 3% in the United States. But the scale of the opportunity could be much bigger. On average a quarter of our online sample (22%) say they might be prepared to donate to a news organisation in the future if they felt if could not cover their costs in other ways.

PROPORTION THAT MADE A DONATION TO A NEWS ORGANISATION IN THE LAST YEAR/WOULD CONSIDER DONATING IN THE FUTURE

Q7ai. You said you have accessed paid for ONLINE news content in the last year. Which, if any, of the following ways have you used to pay for ONLINE news content in the last year?

Q7c_DONATE_2. Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement. I would consider making a donation to a news outlet I like if they were unable to cover their costs in other ways.

Base: Total sample in each market.

In qualitative responses, donations seem to strike a chord with those who are worried about fake news and the independence of the media.

The Link between News Literacy and Paying for Online News

Success in raising donations (or acquiring new subscriptions) is likely to be linked to the extent to which consumer awareness can be raised about the value of journalism and the financial difficulties being faced by many news organisations.

One of our new questions this year reveals that more than two-thirds of respondents (68%) are either unaware of the problems of the news industry or believe that most news organisations are making a profit from digital news. In reality, most digital news sites are operating at a loss, subsidised by investors, alternative revenue streams, or historic profits from broadcast or print.

Those that were aware that digital newspapers are making a loss (10% of our sample) are more likely to pay for a news subscription or give a donation. More widely, this year we have identified different levels of news literacy within our online sample — and the next chart shows a clear link between knowledge about how the news industry works and likelihood to pay in the future.

This helps explain why the Guardian’s messaging — which flags ‘how much quality journalism costs to produce’ — has been so successful. Raising awareness about the problems of the industry, consistently applied, will resonate with those people who trust news and find it valuable, and is likely to make all reader payment models much easier to implement in the future.

Public Service Broadcasters Under Threat

Many public service broadcasters across Europe have faced increasing pressures over the last year. Some politicians and sections of the public, routinely criticise PSBs for being biased — often from a partisan point of view — while some publishers claim that their existence makes it harder for them to make a profit in an already-challenging environment. This culminated dramatically in Switzerland, where a recent referendum asked citizens to vote on the abolition of the licence fee. The result, however, indicated strong support for public broadcasting, with 72% voting to keep it. Meanwhile, in France President Macron in France has reportedly described public broadcasters as a ‘disgrace’ and has pledged to make big changes. In Denmark, a right-wing coalition government has pushed through cuts at the main public broadcaster (DR) of 20% over the next five years, while the BBC needs to find £80m in savings from its news division over a similar time period.

Criticism of public service media comes at a time when media fragmentation and digital disruption, combined with the rise of fake news, has led some commentators to argue that investment in public media is more necessary than since the end of the Second World War.20 Public broadcasters and their websites tend to have the highest trust scores in our survey, at least in countries where their independence is not in doubt. In these cases, overall trust in the news also tends to be higher.

There is also little independent research supporting the idea that public broadcasters have a negative impact upon commercial publishers.21 Our 2016 report highlighted that people who use public service media are no less likely to pay for online news. More broadly, the proportion of people who exclusively get their online news from public broadcasters is very low. In the UK 14% only use the BBC as an online news source, but the figure for PSBs elsewhere is 5% or lower. Even in countries, like Finland, Denmark, and Norway, where investment in public media is considerable, most people who use a public broadcaster supplement this with news from other commercial sources.

It is certainly true that many public broadcasters do attract large online news audiences. But almost all are more widely used offline. The best performing — typically those in Northern and Western European countries — have a weekly online news audience that’s around half the size of its offline audience. In countries where public broadcasting has traditionally received less support, that figure drops to around a one-third or less. This pattern remains largely unchanged from when we made a similar comparison in our 2016 report, and could present a challenge for public broadcasters in the future as offline news use dwindles.

Ad-Supported News Models and the Battle for Global Reach

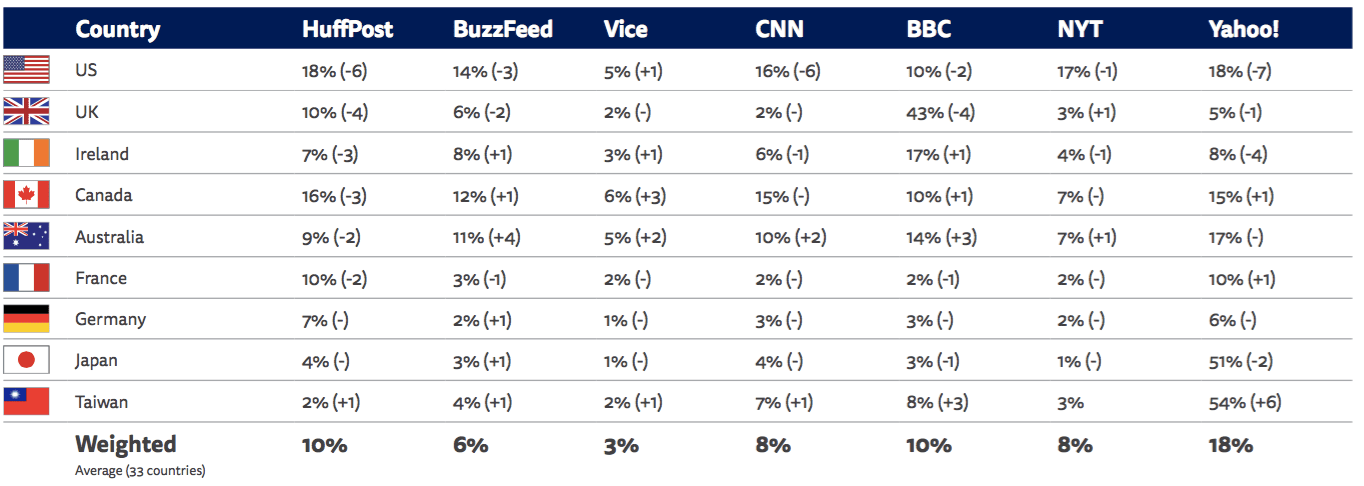

Despite the shift towards reader payment models, it is worth remembering that the majority of online news consumption still happens through free websites, largely supported by advertising (or through public subsidy). This is particularly true for a number of media companies that have set out to create truly global brands. In the last few years many of these brands have been focusing on building up a local reporting presence in a number of countries, sometimes using local partnerships. In the following table, we compare some of the leading companies in terms of weekly reach, by country but also weighted by population.

Yahoo! (18%), one of the internet’s first portals, remains by far the most popular global player even if it does largely aggregate content rather than produce original journalism. It is strong in North America, Latin America, and Asia.

WEEKLY ONLINE REACH OF GLOBAL NEWS BRANDS – SELECTED MARKETS

Q5B. Which of the following brands have you used to access news online in the last week (via websites, apps, social media, and other forms of internet access)?

Base: Total sample in each market. Note: Weighted average calculated using population data from Internet World Stats and the World Bank: weighted = (country population * percentage adults * internet penetration * percentage accessed)/total population of all countries surveyed. Brazil, Mexico, and Turkey are not included due to the absence of reliable data about their urban population. Bulgaria is not included to maintain comparability with last year. Figures for NYT are based on data from 15 countries.

Weekly reach of the rebranded HuffPost is down in most of the countries we measure, perhaps affected by changes to Facebook algorithms, while BuzzFeed News is also down in the US and UK but generally up elsewhere. Traditional news brands, the BBC and CNN continue to build audiences in multiple languages alongside their broadcast output, which they monetise through advertising and sponsored content.

Ad models continue to be undermined by low rates of return, fraud, and increased consumer concerns about privacy. After a pause in growth last year, the use of ad-blockers is on the rise again, alongside privacy browser extensions that allow specific advertisers to be blocked. More than four in ten (42%) now use blockers in Greece (+6) with significant increases in Germany (+5) and the United States (+4). Concerns about privacy may be driving these changes along with greater awareness.

Smartphones and New Devices

The importance of smartphones — and our dependence on them — shows no sign of slowing down. On average 62% of our sample say they use the smartphone for news weekly (+6), only just behind the laptop/computer at 64%. In most countries, smartphone reach for news has doubled in six years.

In the UK, as one example, we now see the smartphone overtaking the computer as the MAIN (preferred) device for accessing news. The tablet has started to decline in importance as smartphones have become more powerful and versatile.

These trends are important because shorter audience attention spans and smaller mobile screens are affecting the type of news content produced. Visually rich formats such as Snapchat, Instagram, and Google (AMP) stories are starting to offer new opportunities for mobile storytelling, using native taps and swipes to break up narratives. Pictures and videos need to be reformatted using vertical aspect ratios and often annotated with text to work in a mobile context.

Video News Consumption over Time

Consumption of online video has grown in recent years, largely through the adoption of native video formats by social media platforms (autoplay, short texted clips, Facebook Live, Periscope, Snapchat video, etc.).

The social video trend may help explain significant country-based differences in consumption, where the highest level of usage tends to be in countries with higher social media use and more offsite traffic.

Splitting this down further, the next chart shows that the majority of news video is now consumed offsite (51%). Facebook alone (33%) accounts for as much video consumption as all news websites put together (33%). But an even larger number (35%) reject news video entirely; that figure rises to more than six in ten in the UK (62%) and over half of our German sample (56%).

PROPORTION THAT USED ONLINE NEWS VIDEO OFFSITE AND ONSITE

All markets

Q11_VIDEO_2018a. Thinking about consuming online news video (of any kind) over the last week, which of the following did you do?

Base: Total sample in all markets.

Preference Remains for Text

In a number of countries we have been tracking content type preferences since 2014 and in all countries we still find an overwhelming preference towards reading rather than watching. The US has pushed furthest towards video, with 12% saying they mostly consume news in video (+2), but even here 62% say they mostly prefer to consume in text. This figure rises to 86% in Finland. There have been some changes over time (especially in the US and Spain), but these have been modest given the increase in exposure to video through social media.

More Videos Required?

There are commercial pressures to push consumers towards more video, not least because ad premiums are generally higher. But would consumers be happy if text stories were replaced with video? The result of this question is fascinating as it once again reveals a split between different countries and cultures. All Asian countries (including Japan) lean towards wanting more online news video, even if that means sacrificing text. In the US and Northern European countries there is a strong vote for fewer online videos. Age does not seem to be a significant factor.

These differences do not seem to be related to underlying preference, as two-thirds of respondents in Asian countries say they mostly prefer text. The explanation is more likely to be connected to a certain weariness picked up in our European and US focus groups about the amount and type of video being pushed through social media feeds (e.g. Facebook’s news feed).

In some groups, people post videos all the time …

(M, 30–45, Brazil)

To me it is about the amount of time. I mean I like visuals when you can put a chart, I like photographs, but I don’t want someone to dictate to me how long I have to watch it for.

(M, 30–45, Brazil)

Some of the reluctance to use news video online comes down to a perceived loss of control, while other factors include limited data when on a smartphone and the difficulty of accessing sound on the move. Meanwhile publishers are struggling to monetise short-form formats in particular, with changes in Facebook strategy and algorithms proving an additional frustration. Many are now pivoting away from short-form video and looking for other opportunities.

The Rise of Audio and the Role of Podcasts

Podcasts have been around for many years but these episodic digital audio files appear to be reaching critical mass as a consequence of better content and easier distribution. The New York Times has found success with its Daily Podcast, a 20-minute audio briefing, which has been downloaded more than 100m times. In the UK, the BBC has hundreds of podcasts, most reformatted from radio output. Connectivity is improving in cars, new audio devices are making discovery easier, while advertising and sponsorship opportunities are growing.

PROPORTION WHO ACCESSED A PODCAST IN THE LAST MONTH

Q11F_2018. A podcast is an episodic series of digital audio files, which you can download, subscribe, or listen to. Which of the following types of podcast have you listened to in the last month?

Base: Total sample in each market.

Overall, a third of our entire sample (34%) listens to a podcast at least monthly but there are significant country differences. Podcasts are twice as popular in Ireland (38%) as they are in the UK (18%) despite the BBC’s extensive, well-promoted, and high-quality podcast output. One theory is that podcasts tend to perform best in countries like the US (33%) and Australia (33%) where people spend a lot of time in their cars. The lower levels of usage in the Netherlands (18%) may relate to shorter commuting distances and more bike travel. But this can’t be the full explanation. Loyalty to radio, levels of supply, and the amount of promotion will also be important factors.

Proportionally under 35s listen to twice as many podcasts as over 45s. This is not surprising given that this is a generation that has embraced both smartphones and on-demand services such as Netflix and Spotify. Older groups, by contrast, remain more likely to listen to radio.

Voice-Activated Speakers More than Double

One further driver of on-demand audio growth has been the emergence of voice-activated speakers. These allow access to existing podcasts as well as new formats such as automated news audio briefings. Media companies like Quartz are also developing apps (or ‘skills’ as they are known) that allow conversational interaction with the devices.

The Amazon Echo range (using the Alexa assistant) is the market leader but is only available in a few markets like the US, UK, Germany, and Australia. South Korea’s tech companies Naver and Kakao have their own devices, Apple has launched the HomePod, while the Google Home and Google Assistant will be expanded to over 30 countries this year. Usage for any purpose has more than doubled in early adopter markets. Almost one in ten (9%) now use them in the United States, 7% in the UK, and 5% in Germany.

PROPORTION THAT USE A VOICE-ACTIVATED SPEAKER (2017–18)

Selected markets

Q8A. Which, if any, of the following devices do you ever use (for any purpose)?

Base: Total 2017-18 sample in each market.

And for News?

Three-quarters of owners use their speakers for listening to music, but news and information is also an important element. Almost half (43%) access news in some way (flash briefings or similar). Weather is popular (67%), while six in ten (61%) access quick facts. More than one in ten (14%) say they use the device to listen to podcasts.

Conclusion

Concerns about the quality of information that emerged in our data last year seem to have solidified now across our 37 countries. Looking back, we can see that disillusion with Facebook set in as early as 2016 while this year’s focus groups show heightened worries about privacy, heated conversations, and unreliable news. While Mark Zuckerberg has pledged to ‘fix’ Facebook, politicians in some countries are looking to seize this opportunity to undermine or control the media. In authoritarian countries, in particular, we see often-draconian laws being introduced with extremely unclear definitions of what fake news means.

This is particularly worrying, because, as our report documents, the root causes of this crisis of information do not all lie in the hands of technology companies or malevolent foreign powers. Indeed, our research suggests that audiences are more likely to blame media publishers for spinning or twisting facts in a world that often feels more angry and more partisan. Some may be enjoying the discomfort of tech executives as they get hauled in front of powerful politicians, but the implications could be serious if new regulation makes it harder for journalists to hold the rich and powerful to account.

In the light of this, the challenge for media companies is two-fold. First, there are the difficulties involved in navigating an increasingly polarised political climate. From Donald Trump in the United States to Victor Orbán in Hungary, journalists are faced with the choice of sticking to the facts or taking sides. A partisan approach risks inflaming passions and potentially alienating some readers, while a more balanced approach can lead to false equivalence and undermining trust of both sides.

The second challenge is economic and has been building for some time, but may be exacerbated for some by Facebook’s decision to focus less on news. As our country pages document, journalist lay-offs continue as media companies look to cut costs and diversify revenue streams. Fake news has to some extent woken people up to the importance of quality news, but that narrative only seems to be true for a relatively small subset of the audience; those with more money, those with more education, those who trust the news media, and often those on the political left. Others remain less engaged and less trusting of media than ever.

This year’s data show that the move to subscriptions and reader payment is real if unequally distributed. This in turn raises new questions about a two-tier system where those with the least money also have the worst information. In some European countries, PSBs may be part of the answer but many are losing audiences and legitimacy in the move to online, with their funding increasingly questioned by hostile politicians. Donations and membership are emerging as alternative routes to squaring the circle of open access and high-quality content but it is far too early to know how far this can develop.

Elsewhere, other potential solutions are being tried to help to sustain quality journalism. These include many more examples of cooperation between publishers over journalistic investigations, and sharing of technology or data.

This year has been a reminder that things that once seemed certain — the importance of Facebook and the online advertising model — can shift quickly. Nothing stands still for long; new technologies like voice-activated interfaces and artificial intelligence are on the way, offering new opportunities but also new challenges for audiences, regulators and media companies alike. The future of news remains uncertain but these pages offer some hope at least that quality content may be more rewarded in the future than it has been in the recent past.

- Polling was done before the full effect of Facebook’s January algorithm changes had come into effect — perhaps with the exception of the United States. ↩

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/kathleenchaykowski/2018/03/06/facebooks-latest-algorithm-change-here-are-the-news-sites-that-stand-to-lose-the-most/#2b70d00334ec ↩

- https://techcrunch.com/2017/11/01/instagram-whatsapp-vs-snapchat ↩

- This term was coined by danah boyd: http://www.zephoria.org/thoughts/archives/2013/12/08/coining-context-collapse.html ↩

- https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/02/world/asia/malaysia-fake-news-law.html ↩

- https://www.edelman.com/trust-barometer ↩

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/global-opinions/wp/2017/12/11/the-polish-government-is-cracking-down-on-private-media-in-the-name-of-combating-fake-news ↩

- https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/our-research/full-text-when-president-wages-war-press-work ↩

- https://www.theverge.com/2018/1/23/16925898/facebook-trust-survey-news-feed-media ↩

- Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, and Lucas Graves, “News You Don’t Believe”: Audience Perspectives on Fake News, Oxford: RISJ, 2016. ↩

- https://www.poynter.org/news/fake-news-probably-wont-affect-outcome-germanys-election-heres-why ↩

- https://www.cnbc.com/2017/03/14/heres-why-the-dutch-election-is-resilient-to-fake-news.html ↩

- We can see from our data that the audience is overwhelmingly partisan. For example, over 80% of Breitbart’s audience in the US identifies as right wing. In the UK around 75% of the Canary’s audience identifies as left wing, though with a small base. ↩

- We previously wrongly reported that Breitbart has launched a German site, although they had only announced plans to do so which they later withdrew ↩

- PI News says it is engaged in a ‘fight against the Islamisation of Europe’. See: http://www.pi-news.org/about-us/ ↩

- https://www.zeit.de/2016/25/afd-compact-juergen-elsaesser/komplettansicht ↩

- A round up of alternative sites in Czech republic by Forum24: http://forum24.cz/kdo-nas-dezinformuje-aktualni-prehled-hlavnich-zdroju-a-siritelu-fake-news-v-cesku/ ↩

- http://money.cnn.com/2017/09/26/media/washington-post-digital-subscriptions/index.html ↩

- https://www.economist.com/news/britain/21735046-two-years-ago-newspaper-was-making-existentially-worrying-losses-next-year-it-hopes-break ↩

- http://www.niemanlab.org/2018/04/emily-bell-thinks-public-service-media-today-has-its-most-important-role-to-play-since-world-war-ii/ ↩

- Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, Richard Fletcher, Annika Sehl, and David A. L. Levy, Analysis of the Relation between and Impact of Public Service Media and Private Media. Oxford: RISJ, 2016. ↩